This is a revised version of a post I published on this date ten years ago.

On June 18, 1945, at a White House meeting with the Joint Chiefs of

Staff, the Secretary of War and the Secretaries of the Army and Navy,

President Harry Truman approved plans for the invasion of Japan. Along

with the President the other key participants were General George C

Marshall and Admiral Ernest King, Chiefs of Staff for the Army and Navy.

Richard B. Frank's 1999 book, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, using information that had only become available in the prior decade recasts

our understanding of the events

of the last few months of WWII and the endgame with Japan, culminating

in its surrender on August 14, 1945 (the formal ceremony took place on

the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2). These sources include

Russian

archives which became available after the fall of the Soviet Union; the

release, after Emperor Hirohito's death in 1989, of his lengthy account

(dictated in early 1946) of those months; the completion of the Japanese

War History Series and the release of additional American intelligence

information, most importantly, of the Magic Diplomatic

Summaries. The Magic materials were a daily summary of intercepted

Japanese diplomatic cables produced by U.S. intelligence

analysts.

These summaries, distributed to senior American policy makers, provide

us with a new window on the information

they were receiving about Japanese intentions and the contemporaneous interpretations placed on that information.

In recent decades the end of the war has focused on the American

decision to use the newly developed atomic bombs, but Frank's book covers

much broader ground, opening our eyes to a vision of a surprising

counterfactual history in which the U.S. may not have invaded Japan, even

if the bombs had not been dropped and the war had continued beyond

mid-August 1945.

What were Truman and the others thinking about as they entered the meeting room on June 18?

The night before, Truman had written in his diary that the decision whether to "invade Japan [or] bomb and blockade" would be his "hardest decision to date".

The men entering the meeting knew the American public was increasingly war-weary and shocked by the

enormous casualties of the past year. In the first 30 months of WWII,

the U.S. suffered 91,000 battle deaths, an average of about 3,000 a

month. With the D-Day landings in France and the

American assault on Saipan in the Pacific in June 1944, the toll accelerated. During

the next twelve months, 196,000 Americans died in combat, an average of

more than 16,000 a month (1).

With the end of the European war in May, public pressure to start

bringing the troops home was increasing, though a poll that month found

the U.S. public still preferring unconditional surrender to a negotiated

end to the war by a margin of 9 to 1.

In

early 1945 the Pacific war grew even more horrendous as we approached

Japan. On the 8-square miles of Iwo Jima over five weeks in

February and March 1945, 7,000 Americans died and 17,000 were wounded

fighting 21,000 Japanese soldiers; the desperate nature of

the fighting captured in the words of General Graves Erskine at the

dedication of the 3rd Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo:

"Victory

was never in doubt . . . What was in doubt, in all our minds, was

whether there would be any of us left to dedicate our cemetery at the

end, or whether the last Marine would die knocking out the last Japanese

gun and gunner."

Iwo was followed on

April 1 by the American landing on Okinawa. In the next ten weeks

another 50,000

American soldiers and sailors were killed or wounded in the course of

eliminating a

Japanese garrison of 92,000 in a struggle that came to resemble the

trench warfare of WWI, the grinding and unrelenting nature of which had

also resulted in thousands of additional psychiatric casualties.

For

a better idea of what the awful fighting conditions read

With The Old Breed: From Peleliu To Okinawa, Marine veteran E.B. Sledge'

s unforgettable account of combat on the hillsides

under continuous shelling amidst the mud and broken bodies. Along with

these campaigns significant fighting continued in the

Philippines, at sea, and in smaller operations on islands across the

Pacific as well as by our British, Australian and New Zealand allies

engaged across the Pacific and in Burma.

Along with the

weariness, the increasing toll from these battles enraged American

civilians and soldiers. Many accounts by American soldiers bitterly

reflect

on the senselessness of what the Japanese army was doing - they had clearly

lost the war by this point - why sacrifice themselves and cause more Americans to die in the process? There had been great

anger against Japan since the start of the war, triggered by the

surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, and amplified by increasing reports of atrocities

against American prisoners (according to polling data public anger

against the Germans was less until the discovery of the Nazi death camps

at the end of the war). Now it was being ratcheted up even further as

thousands of Americans died needlessly because the Japanese could not

recognize they had lost the war, inducing a high degree of

fatalism among the U.S. soldiers who were told that summer they would be

part of the invasion force.

Those meeting on June 18 knew the Allied policy was

unconditional surrender for Japan as set by FDR and Churchill at the

Casablanca Conference in 1943.

They knew that the Magic Summaries showed no Japanese government disposition for peace on these terms, and that the military members who dominated the cabinet still hoped that enough casualties could be inflicted upon the invading Americans so a peace, more favorable to Japan, could be negotiated.

They

knew that Japan still had 2 million military personnel stationed

outside Japan, scattered across Pacific islands, New Guinea, the Dutch

East Indies, China, Korea, Burma and Indochina and they wanted to force a

formal surrender by the Japanese government to avoid years of piecemeal

fighting with each of these isolated forces.

At the

June 18 meeting the broad strategy for the invasion of Japan was set

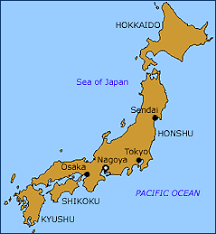

out, and approval given to initiate formal planning for the invasions. The first landings would be on the island of Kyushu, the

southernmost of the four main Japanese homeland islands, on November 1.

Kyushu's seizure was required so that the Air Force could build

the airfields needed for the fighter aircraft to provide air cover for

the climactic landing on the Honshu plain near Tokyo planned for March

1, 1946.

Truman

was told the military planners assumed that about 760,000 American

troops would face 350,000 Japanese on Kyushu supported by about

2500-3000 aircraft. Although the Joint Chiefs unanimously supported

this decision, the President

was not told that the Navy, unlike

the Army, did not believe an invasion would ultimately be needed and

that in Admiral King was only supporting preparations for the

landing on Kyushu. King believed a blockade and aerial bombing would

bring about surrender. His Pacific commander,

Admiral Nimitz,

had recently told King he had changed his mind about supporting the

invasion

"after further experience in fighting against Japanese forces".

Six weeks later, American intelligence had assembled a completely

different picture of what awaited on Kyushu. The Japanese Army had

figured out that the American landing would be on the island and bet

everything on a strategy of inflicting maximum casualties in order to

achieve a negotiated settlement to the war, involving preservation of

the Emperor, no Allied occupation of Japan, and retaining at least some

portions of Japan's overseas empire. What had changed in those few

weeks?

- Instead of 350,000 troops, American intelligence now estimated there

would be 650,000 (it was discovered after the end of the war that

the Japanese had actually packed 900,000 troops onto the island), and the Japanese had identified the specific American landing beaches.

- Instead of 2500-3000 aircraft, the Japanese had between 6,000 and

10,000 and were going to employ many of them in waves of kamikaze

attacks against vulnerable transport ships packed with thousands of

American troops (the Okinawa kamikaze attacks, which cost the lives of 5,000 Americans, had been on warships)

- The entire civilian population of the island had been mobilized,

armed (in some cases just with hoes and spades) and trained to attack

the American soldiers when they came ashore, creating a situation where

the U.S. military would be unable to distinguish between soldiers and

civilians, resulting in enormous casualties on both sides.

- The Japanese military had issued orders to kill all Allied prisoners of war once the American invasion started.

During these weeks the Magic Diplomatic Summaries

indicated no improvement in the prospects of a peace offer from Japan on

Allied terms. An enormous literature on this topic has been created

over the past half-century. For a time in the 1960s and 1970s,

revisionist historians held the high ground with claims that Truman and

company ignored Japanese peace overtures because of concerns about the

rising power of the Soviet Union, leading to the use of the bomb as an intimidation move against the Russians. As more documents and information have become available,

along with revelations of how some revisionist historians distorted and

cherry-picked existing data, the tide of revisionism has receded.

Without rehashing the entire saga, suffice it to say that Japan's

foreign minister admitted after the war that the Cabinet never agreed on

a specific route for terminating the war, and the Magic intercepts

revealed a series of communications between the government at home and

its ambassadors that were confusing in many respects but always clear in

one: unconditional surrender was unacceptable and future events (i.e,

casualties inflicted on Americans during the anticipated invasion) might

lead to termination of the war on more favorable terms. For those

interested in knowing more about the rise and fall of revisionism read

this scholarly paper.

According to Franks, the new intelligence would have led Admiral King to withdraw his support for the

Kyushu landing, precipitating a new strategic review by President Truman

in the second half of August, particularly in light of the President's

concern over American casualties, if the war had not ended on August 14

after the bombing of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9) and

the entry of the Soviet Union into the war on August 8.

At

the same time, the Air Force had come up with a new approach to

strategic bombing that it planned to implement in September 1945. Unlike the

massive incendiary attacks which burned down large parts of Japan's

biggest cities

between March and June, the new campaign focused on a small

number of key rail yards, bridges, tunnels and ferries. The Air Force

had finally realized that with Japan's poor, and mostly unpaved, road network,

the distribution of food supplies could be paralyzed by disrupting fewer

than 100 rail and shipping locations. With Japan's population already

on the brink of starvation, the effect of this campaign would have been

catastrophic. It was already so bad that, even with the war

ending in August, as late as March 1946 the average daily ration for

Tokyo civilians, nominally only 1,042 calories was, in reality, closer

to 800 calories, and starvation only avoided by massive U.S. food

supplies.

This strategic review

would have provoked intense controversy within the Administration since

the U.S. Army was still committed to the invasion strategy. There is no

indication that Truman ever knew of the new intelligence on the

Japanese military buildup on Kyushu or of the new Air Force bombing plan,

and with the end of the war it was not necessary to raise the issue to

the Presidential level.

All of this creates a

hypothetical future where no American invasion of Japan occurs even if

the war went on beyond mid-August. The likely results:

- Continued American blockade of the Japan home islands and complete

disruption of the food supply by the Air Force bombing campaign inducing

famine in the civilian population.

- The invasion of lightly defended Hokkaido (the northernmost home island of Japan) by the

Soviets in September 1945 - one of the revelations from the opening of

the Soviet archives in the 1990s.

- The British proceeding with their planned amphibious landing in

Malaya, scheduled for early September, and incurring heavy casualties

against Japanese forces who had anticipated the landings.

- Continued fighting in the Philippines, on smaller islands across the Pacific, and in China.

- Huge death tolls of Asian civilians under Japanese occupation

(primarily in China and secondarily in Southeast Asia), estimated to be

100,000 to 250,000 a month from famine, disease, imprisonment and execution.

The question is how long could Japan have survived in this scenario and

whether the ending would be an organized surrender of all Japanese military forces or a

disorganized collapse in which scattered fighting continued across the

Pacific and mainland Asia.

The end of the Pacific war, just as that of the European war, would have been grim under any scenario.

This post only begins to touch on the issues impacting the end of the war and covered in detail in Downfall.

Frank discusses the Soviet attack on Japan in Manchuria and its impact

on the Japanese government, the lead up to, and the impact of, the

Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks, Japanese cabinet deliberations and

debates over peace terms, the controversy over American casualty

estimates for the invasion (for an excellent summary of the complex history and methodology of the casualty estimates read "A Score of Bloody Okinawas and Iwo Jimas" by DM Giangreco in Hiroshima In History, edited by Robert James Maddox (2007)) and the nuts and bolts of U.S. and Japanese

military operational planning.

The book is

thought provoking, giving the reader a greater appreciation of the

information decision makers had available, the different paths that

could have been followed and the consequences that would have flowed

from them. It is particularly valuable in conveying what it is like to

have to make decisions affecting the lives of millions with only the

information you have available at the time and without the advantage of

hindsight.

It strikes THC that these events would be a terrific instructional tool

for students and others regarding real-life contingencies and

decision-making. A course where students were assigned roles in the

American civilian and military hierarchy and then fed information as it

became available and asked to make decisions based on the available

information would make for a memorable learning experience, and would

probably be humbling and sobering to those who think everything looks as

clear to the participants at the time as it does to others in

hindsight. It could be done in two parts - the first based upon what we

know happened through the decisions to drop the atomic bombs and accept

the continued role of Emperor Hirohito and a second based on a scenario

where the bombs are not dropped and the war continues. Most

importantly, those participating should be challenged along the way by

the instructor(s) but not led to any predetermined outcome.

----------------------------------------

(1) 196,000 is double

the total number of American combat fatalities in the 80 years since 1945

including Korea, Vietnam, The Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Here's the opening:

Here's the opening: