It was seventy years ago this month that Berlin became a city divided, a status it retained until the Berlin Wall, constructed in 1961, came down on that memorable evening in November 1989.

The event occurred amidst the turmoil of the Berlin Blockade and the relief airlift launched by the United States and Britain to keep its sectors of the city supplied.

With the end of the Third Reich in May 1945, Berlin was divided into four zones of occupation (Soviet, American, British, and France) but governed as a unified city. The entire country was also divided into four zones, but Berlin lay completely within the Soviet zone. In order to support their occupation forces and supply its sectors, the Western Allies had the right to use certain rail and road lines to connect their zones in Western Germany with their Berlin sectors. Governance of the entire structure was through the four-power Allied Control Council (ACC).

(

Berlin: Occupation Sectors from Air Force Historical Support Division)

As relations between the Soviet Union and the West worsened, Stalin decided on a plan designed to force the U.S., Britain, and France to choose between withdrawing from Berlin or agreeing to his wishes regarding the future of Germany. On March 20, 1948 the Soviet delegates walked out on what proved to be the final meeting of the ACC. Over the next three months the Soviets intermittently interfered with Western shipments to Berlin.

Germany was in the middle of an economic crisis and the Soviets refused to agree to currency reform efforts. On June 18 Britain, French, and the United States announced the introduction of the Deutsche Mark (DM) as the new currency in their sectors. The following day, the Soviets began permanently restricting and, within a few days, completely blocking the rail and road supply links to the Western Allies sectors in Berlin. Only the air corridors remained open but the Soviets thought the Allies incapable of the massive airlift needed to maintain the civilian population of Berlin. As of late June, western Berlin had only 36 days of food supplies and 45 days of coal.

From a military perspective the West was vulnerable. There were only about 21,000 British, American, and French military personnel in Berlin and fewer than 150,000 troops (and only one combat ready division) in West Germany, while the Soviets had 1.5 million soldiers in East Germany.

President Harry Truman was confronted with deciding how to respond. Though the U.S. commanders on the ground in Germany and Europe, Lucius Clay and Curtis LeMay, urged a strong response, he was getting different advice from his senior civilian and military advisers in Washington.

Army Secretary Kenneth Royall, Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, acting Secretary of State Robert Lovett, and Truman's military advisor, Admiral William Leahy all believed the Western Allied position in Berlin to be militarily indefensible and quickly overrun if the Soviets attacked. Army Chief of Staff Omar Bradley advised that it would be better for the U.S. to pull out of Berlin on its own terms, than to be forced out. Walter Bedell Smith, the current U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, and former chief of staff to General Eisenhower in WW2 also thought America should leave Berlin. Several months into the crisis, Bedell Smith remarked:

"Our present hysterical outburst of humanitarian feeling keeps reminding me that just three and a half years ago I would have been considered a hero if I had succeeded in exterminating those same Germans with bombs."

The initial response from our British and French allies was also undecided on how to respond.

And there was a political aspect, with a presidential election coming in November. Thomas Dewey had just wrapped up the Republican nomination and was considered by the press as a sure victor in November. Truman was also facing what looked like a strong third-party challenge to his left from Henry Wallace.

Wallace, an Iowan, had been Secretary of Agriculture under FDR, then served a Vice-President during Roosevelt's third term, before being forced off the ticket in 1944 by Democratic party bosses, clearing the path for Truman, and returned to FDR's cabinet as Secretary of Commerce. He was also, as Andrei Cherny writes in

The Candy Bombers (a highly recommended account of the Berlin Airlift), a "

profoundly strange" man who "

believed the future could be foretold by markings on the Great Pyramid of Egypt", and convinced FDR to add the pyramid to the dollar bill. He was also involved with theosophists (for more on this odd group read

Madame Blatavsky and the Birth of Baseball).

Wallace was also not unsympathetic to the communists. In September 1946 he was fired by Truman after attacking his policy of opposing Soviet domination in Europe. As Truman moved to counter Soviet aggression, Wallace became even more outspoken. In March 1947 in response to the announcement of what became known as the Truman Doctrine under which it became the "policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressure", Wallace declared that "

America will become the most hated nation in the world", placing all blame on America for the emerging Cold War. He opposed the Marshall Plan calling it a "

blueprint for war". Throughout 1947 Wallace spoke to enthusiastic audiences of up to 30,000 people announcing, at the end of the year, a third party presidential run as the Progressive Party candidate. Wallace knew he could not win an election from hope to deny Truman victory and ultimately allow Progressives to take over the Democratic Party.

As 1948 began international tensions already high, became worse after a successful communist coup in Czechoslovakia, the last remaining free country in Eastern Europe. Wallace excused the coup on the grounds that the communists were driven to it by threats of a Rightist coup. It should come as no surprise that as the Soviets ratcheted up pressure on Berlin, Wallace urged an American withdrawal in order to preserve the piece.

From a political perspective Truman was faced with a strong Republican opponent, and a Wallace campaign that could siphon off much needed votes.

Harry Truman decided to stand firm in Berlin. The logistical obstacles to supply the city were overwhelming but, by trial and error over the next three months along with Herculean efforts by the American and British Air Forces, a viable air corridor was established. We were fortunate that during the next year no crisis erupted elsewhere in the world, as the U.S. had no additional air logistical capacity to deploy. It was all needed to keep Berlin supplied.

At the Progressive Party convention in Philadelphia during July, enthusiasm ran high and Wallace was doing well in the polls. With thirty being the average age of delegates, and three quarters having no prior political involvement, it appeared to be a transformational youth movement.

(

Berlin after WW2 ended, from Rare Historical Photos. com)

In the meantime though, the airlift was transforming American and German views of each other. The horrors of Nazism and hundred of thousands of dead American soldiers left little sympathy for German civilians trying to survive amidst the ruins of their shattered cities. We did want we needed to do to prevent outright starvation, but economically and spiritually the country remained prostrate, and in Berlin there were still food shortages and little rebuilding; that was fine with most Americans but in 1948 the Soviet threat, the determination of the Germans in Berlin to resist the Russians, and their enthusiastic response to the Airlift sparked more public sympathy and interest in American efforts to help German recovery.

One specific event had a profound impact on both Germans and Americans during the blockade. On July 18, 1948, while on approach to Templehof Airport in Berline, C-54 pilot Gil Halvorsen, wiggled his wings and dropped chocolate bars attached to a handkerchief parachute to children waiting below. The prior day while at Templehof, Halvorsen while walking around encountered the children who were watching the planes land and asked him questions about the aircraft. He gave them gum and promised he'd drop them candy the next day after wiggling his wing. Halvorsen continued his daily candy runs and when news reached the airlift commander he organized Operation Little Vittles; soon American children sent candy for the drops and eventually U.S. candy manufacturers made donations; 23 tons of candy were dropped in toto, and Halvorsen became known as The Candy Bomber, giving title to Cherny's book. The candy drops became a symbol of America's willingness to help and of the perseverance of Berliners.

(

C-54 Lands At Templehof,

from wikipedia)

In November Truman pulled off one of the most surprising upsets in presidential history beating Dewey. Ironically, it was the Berlin Airlift that probably was the critical factor. For independent voters it demonstrated that Truman could be tough in protecting America's interests. For potential Wallace voters seeing the reality of the heartless face of communism in its willingness to starve millions of civilians, the American response to help those in need, and the Democratic party's attacks on Wallace as a tool of communism, blunted their progressive enthusiasm. Early in the fall it looked like Wallace was going to get 6-7% of the vote, guaranteeing a Dewey victory, but the campaign collapsed in the final weeks and Wallace polled only 2.5% (1.15 million). Even then it was close; the Wallace vote threw New York to Dewey, while if the Progressive candidate had received only 7,000 more votes in Ohio, and 18,000 in California the race would have gone to the House of Representatives, and 69,000 more in five other states given Dewey an outright victory.

The Western Allies knew winter would be their biggest challenge, as coal needs increased, and worsening weather restricted the airlift on many days. And, in the midst of this, Berlin was scheduled to have its first municipal elections since 1946 in which a communist party faced three non-communist opponents. The Soviets, knowing the communists would lose the election tried a mixture of threats, gifts, and force to intimidate Berliners.

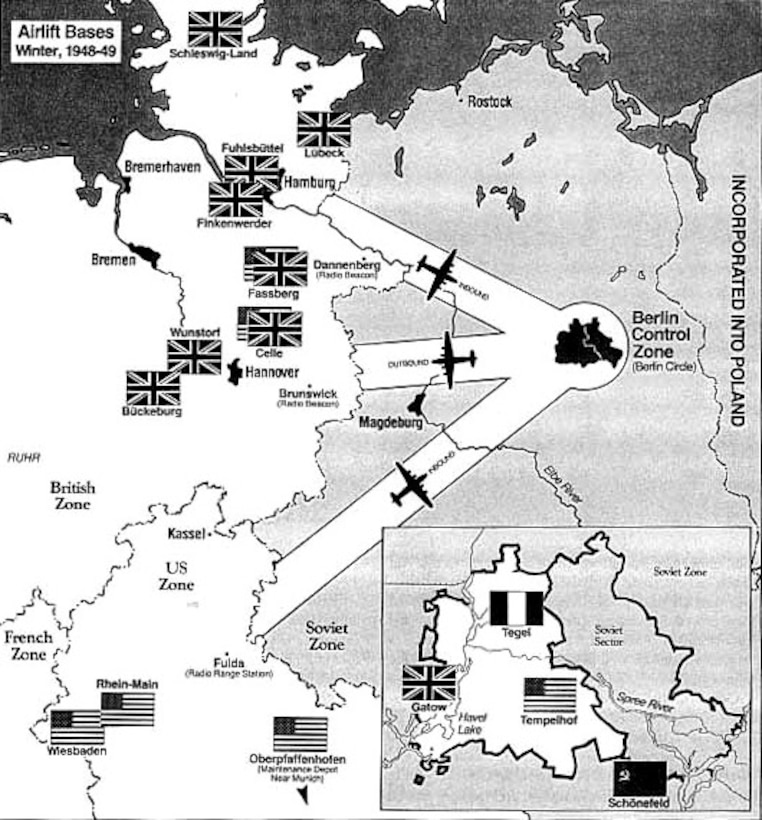

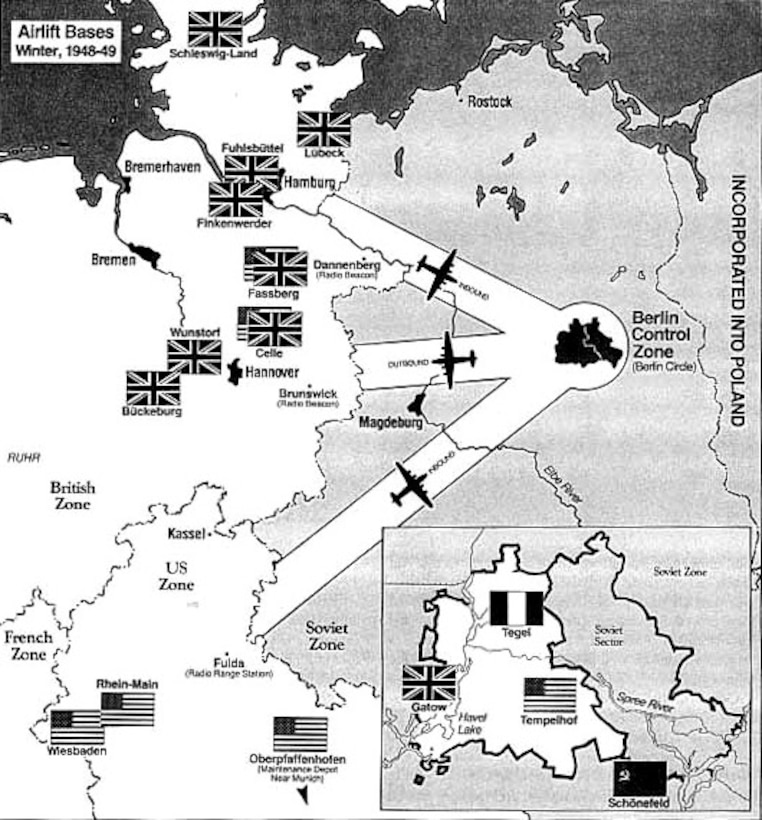

(

Airlift: Winter 48-49, from US Department of Defense)

From the start the city's population, no matter how they disliked the Russians and/or communists knew that if the Western Allies abandoned them, they would have to live under Soviet domination, a fear the Soviets made use of by constantly reminding the populace of the consequences they would suffer if they supported the West, and then were left behind when the British and Americans withdrew.

On November 30 the city parliamentarians of the Soviet supported local communist party held an assembly in which they declared themselves the legitimate government of the city. In conjunction with this, the Soviets accelerated their campaign to discourage Berliners from voting in the municipal elections scheduled for December 5. Along with threats the Soviets made generous offers to those who agreed not to vote; Soviet ration cards, nearly a ton of coal to each household, unlimited amounts of electricity, and a half pound of candy for each school age child. They also reminded Berliners, "

if you vote on the 5th, you vote for war".

Meanwhile, General Lucius Clay, commander of the American garrison in the city, who had become the symbol of Allied defiance of the Russians, found himself stranded in West Germany where he had gone for meetings, because of days of thick fog in Berlin. Worried that his absence would be taken as an indicator of weakened American resolve Clay and his wife boarded a flight during the night of December 4 taking off through the mist. Arriving in Berlin before dawn the fog was so dense the controllers at Templehof refused permission to land because visibility was less than 100 feet. According to Cherny, "

Clay barged into the cockpit and grabbed the microphone from the pilot." Permission to land was granted, the plane landed, skidded to a stop, and was escorted by servicemen with hand held flashlights to its stand, since the pilot could not otherwise see anything on the taxiway.

An overwhelming 86% of eligible Berliners cast their votes on December 5, with the Social Democrats, the strongest anti-communist party of the opposition winning more votes than the others combined. Two days later the newly elected city government took power. With the election, Berlin became divided, with East Berlin governed by the communist party, and the three sectors under Allied occupation having a different government. Though some connections between East and West Berlin continued until the building of The Wall in 1961severed all contact, it would be 43 years before the city would be unified under one government.

One other significant event occurred in December involving the French. Initially the French, suffering through the rise and fall of multiple governments in Paris and with the French Communists, a strong political force, supporting Stalin's actions, hesitated to strongly support the American and French response. However, in August they agreed to build a new airport in their sector to support the airlift, completed in early November, built almost entirely by hand by 17,000 Berliners working around the clock, and having the longest runway in Europe.

There was a problem though. About 400 yards from the runway were two towers of Radio Berlin, the Soviet propaganda arm. They were not illuminated and posed a danger to landing planes. The Soviets refused to move the towers, even though the Americans offered to pay for rebuilding in a different location.

On the morning of December 16, British and American officers at the airport were asked to come to French General Jean Ganeval's conference room for a reception. They found plentiful food but no explanation for their summons. At 1045 they were startled to hear a huge explosion and saw the two Russian radio towers collapse. Ganeval, who had been grossly insulted by Soviet behavior earlier that fall, told his guests, "

You will have no more trouble with the tower."

The Allies and the people of Berlin persevered through the winter; Stalin knew he could not prevail. On May 12, 1949 the Soviets lifted the blockade, though the airlift was not declared ended until September 30, as the Allies continued flights in order to build up a three month stockpile of supplies in case the Russians changed their minds.

In the course of the airlift, the Allies made 280,000 flights to Berlin to deliver more than 2.3 million tons of supplies. Seventeen American and eight British planes crashed during the effort, and 40 British along with 31 Americans died.

In the 1950s, Henry Wallace realized his 1948 Progressive Party campaign had actually been run by communists and expressed regret that he had not understood that at the time.

"Candy Bomber" Hal Halvorsen, a Utah Mormon, remained in the Air Force until 1974.

His final assignment was as group commander at Templehof Airport. Hal

recently celebrated his 98th birthday and splits his time between Utah and Arizona, where he winters.

Hal Halvorsen

Just to the right of the Arch can be seen part of the Colosseum. The Arch was constructed in the early 4th century after the Constantine the Great's defeat of his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312, just outside of Rome. It was the last triumphal monument of the Rome Empire constructed in the city. Even by that time the quality of monumental art had declined, with many of the statutes and facades of the Arch scavenged from monuments of prior centuries.

Just to the right of the Arch can be seen part of the Colosseum. The Arch was constructed in the early 4th century after the Constantine the Great's defeat of his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312, just outside of Rome. It was the last triumphal monument of the Rome Empire constructed in the city. Even by that time the quality of monumental art had declined, with many of the statutes and facades of the Arch scavenged from monuments of prior centuries.

(Reverdy Johnson, from wikipedia)

(Reverdy Johnson, from wikipedia)

(Yep, this is the place)

(Yep, this is the place)