He entered the city through the Porta Asinaria, a gate on the Aurelian Wall, built by the third century emperor who restored a splintered empire. Belisarius and his small army were reconquering the city of Rome for the Roman Emperor Justinian, based in Constantinople. The city had not had a Roman Emperor in sixty years. It was December 9, 536 AD.

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries Rome was the largest city in the world with a population estimated at one million. Even with the slow decline and eventual end of the western Roman Empire, the city remained prosperous (at least relative to much of the rest of the West) into the early 6th century with perhaps 200,000 inhabitants as late as 500 AD.

Yet a decade after Belisarius' entry Rome went through a brief period when it was virtually depopulated and a decade after that the population was still no more than 30,000. Indeed, for a thousand years, Rome's population did not exceed 50 or 60,000 (except for brief periods when refugees from various wars crammed inside its walls) and did not again reach a million inhabitants until the 1930s. What happened?

At the beginning of the fourth century Rome covered about 3,400 acres within the Aurelian Walls, and its total urbanized area may have been 6,000 acres. The city contained 28 libraries, 1,352 street fountains, and 856 communal baths with a capacity of 63,000. To supply the city with 200,000 tons of grain annually and other vital supplies, seventeen ships arrived each day during the sailing season at the city's ports at Ostia. More than 300,000 amphorae containing olive oil arrived each year which, when empty, were discarded into a huge landfill that still exists today containing the rubble of an estimated 53 million amphorae rising 30 meters high and a kilometer in circumference. (Statistics from Rome: A Living Portrait Of An Ancient City, Stephen L Dyson (2010)).

And what would a visitor see in the heart of the city?

The great streets . . . all ended in the same general area, marked by the Capitoline Hill, Forum, Palatine, and Colosseum. Over the centuries this area had grown into a grand display of state architecture . . . There, Romans, provincials, and foreigners gawked at temples, basilicas, theatres, porticos; heaps of marbles . . . gilded capitals, triumphal arches, honorific statues . . . all this was the grand show that reflected the glory of Rome and her empire (Rome: Profile of a City, 312-1308, Richard Krautheimer (1980))Below, Circus Maximus, seating capacity of 200,000. Imperial palace on the Palatine Hill to the left. On the other side of the Palatine were the forums and the Colosseum. (From Roman History Facebook Page)(Interior of Pantheon)

During the 4th century the population slowly declined as Rome ceased to be political capital of the Empire; the Emperors in the east resided in Constantinople while those in the West kept their residences in cities like as Trier and Milan, closer to the frontiers threatened by barbarians across the Rhine and Danube. Even so, as the 5th century dawned it still appeared the city and empire would go on eternally.

Things quickly changed. In 402 the Goths made their first appearance in northern Italy triggering a convulsive series of events (for more see Adrianople) that would lead to the sack of Rome in 410 while other barbarians temporarily overran Gaul and Spain, and Britain was abandoned forever. While some semblance of order was restored in Italy after the Goths moved into Gaul in 414 the province had been devastated. Despite brief periods of stability the Empire in the west continued its decline. In 455 Rome was subject to a second, and more brutal, sacking at the hands of the Vandals who had conquered Roman Africa in 439. The last emperors were mostly figureheads and by 476 the Romanized barbarians who controlled them grew tired of the charade, overthrowing the last emperor (Romulus Augustus) and sending the imperial regalia to the eastern Emperor in Constantinople.

In 493 Theodoric the Ostrogoth seized control of Italy, restoring order and stability until his death in 526. While Theodoric's capital was at Ravenna, he attempted to maintain Rome in the face of its slow deterioration. Krautheimer describes the efforts of Cassiodorus, Theodoric's chancellor:

Try as Cassiodorus might, his efforts to halt the erosion were in vain. Sewers were in need of repairs. So were aqueducts . . . The public granaries had 'collapsed through old age'. . . Bronze statues all over were being looted '. . nor are they mute; the ringing sound they give forth under the blows of thieves . . . wakes the dozing watchman.' Marble, lead, and brass were looted from public buildings . . . Temples, Cassiodorus complains, 'have been handed over to spoliation and ruin' . . . Many of the great mansions, too, had been abandoned . . .The tenements and apartment houses suffered even more. Theodoric the Great has a positive historical reputation for what is seen as his relatively enlightened rule. Of course, "enlightened" is a relative term. He became sole ruler of Italy in 493 when, at a celebration banquet marking the end of a four year war with his predecessor and future co-ruler Odoacer, he terminated the peace agreement by coming up behind Odoacer and, with one swipe of his sword, sliced him from the shoulder down to his waist. He was also responsible for the arrest and execution in 525 of the man often referred to as "the last Roman", the philosopher Boethius, who served as one of his principal administrators.

Theodoric's death the next year triggered succession struggle lasting a decade. Amidst the chaos, eastern Roman Emperor Justinian (527-65) saw an opportunity to fulfill his ambition to reestablish the empire in the west. In 533 the emperor sent his trusted general Belisarius, who had achieved great success fighting the Persians, on an expedition against the Vandals and their capital Carthage, located in modern-day Tunisia. With a small army of 10,000 men, the general gained a quick and stunning victory leading to the collapse of the century old barbarian kingdom in 534. The next year Belisarius seized Sicily and in the fall of 536 landed his force in Italy taking Naples in November and Rome the following month. Outmaneuvering his Gothic enemies he occupied Rome without a fight. It seemed that this war would be ended as quickly and triumphantly as the one against the Vandals.

Instead the reconquest of Italy turned into a long drawn out affair as the Goths rallied and fought fiercely until finally being defeated in 554. It was the Gothic War, not the fall of the western empire in the prior century, which brought the definitive end of classical Rome and Italy. Byzantine and Goth armies marched up and down the peninsula leaving a path of devastation and impoverishment. Maintenance and upkeep of the cities declined and their populations fled to rural areas only to find many of the villas and smaller towns had been pillaged. Some of the aqueducts supplying water to Rome (which changed hands five times during the war) were wrecked and never repaired, leaving parts of the city unable to support a dense population. And little more than a decade after the final triumph over the Goths, Italy was invaded from the north by the Lombards initiating more years of warfare and redividing the province.

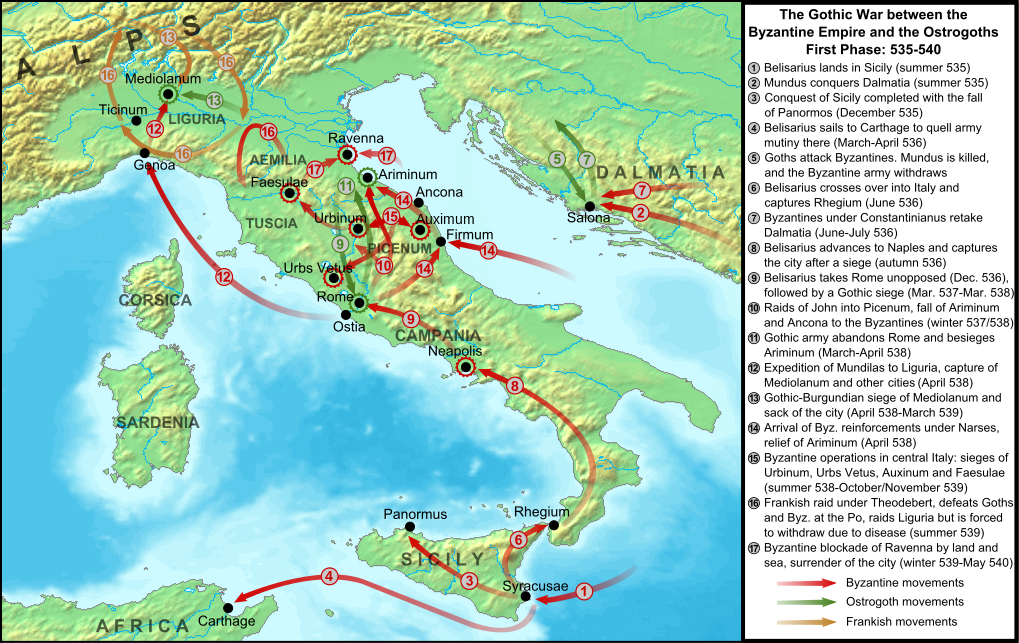

The map below covers only the first phase of the Gothic Wars.

It was during the Gothic Wars that the symbols of the power of the Roman Empire ceased to be used. The last record we have of the Baths of Caracalla operating is in 537, and both the Coliseum and the Circus Maximus saw their final shows during these years.

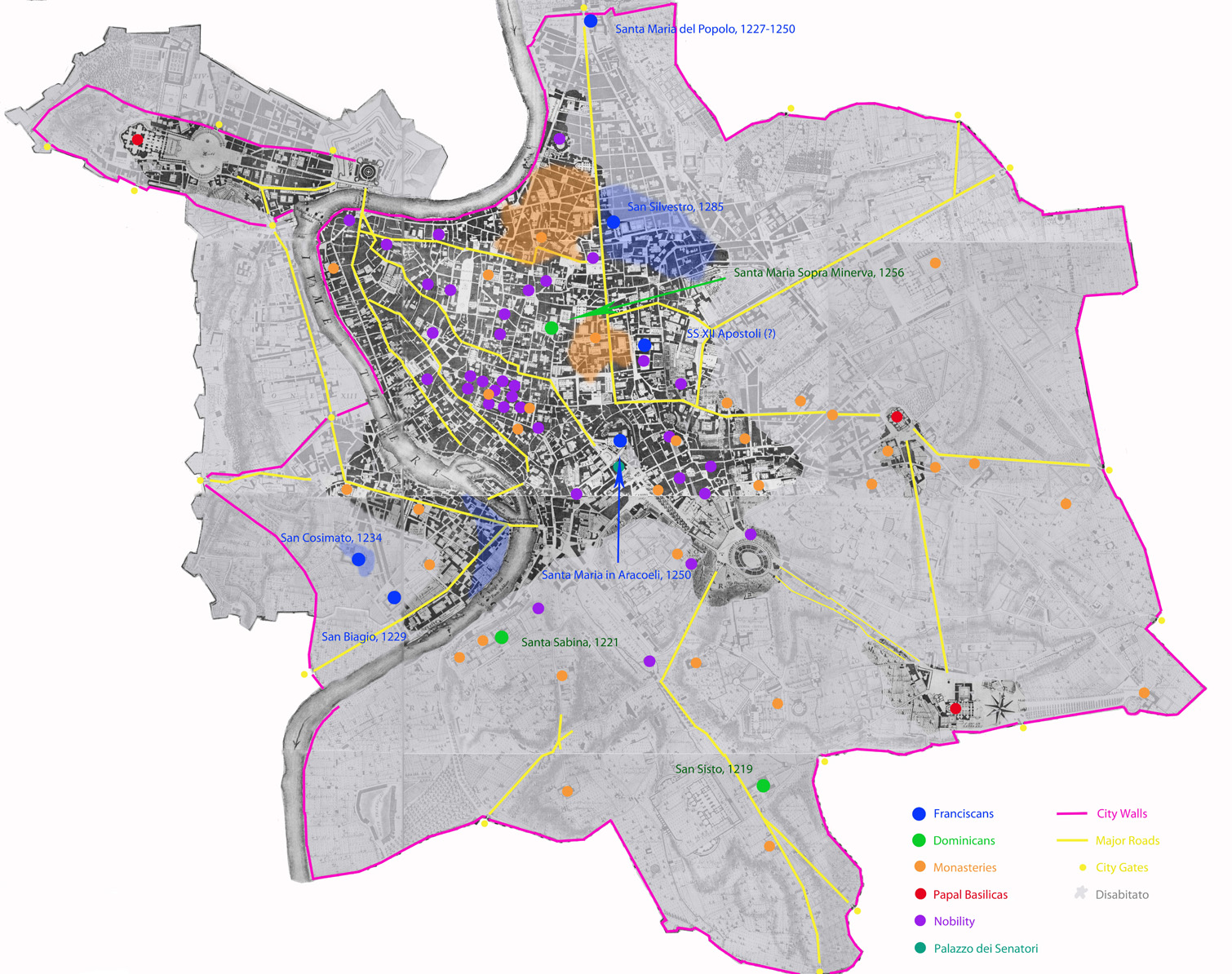

A transformed city emerged from the wreckage of the Gothic Wars in the later 6th century, with a much diminished population concentrated along the Tiber River, particularly on the former Campus Martius on the east bank, and in the Travestere and the area that later became the Vatican on the west bank, where water was more readily available (referred to as the abitato). Large tracts of the ancient city, including the Forums, the hills (including the Palatine on which the Imperial Palace was sited), and the area around the Colosseum, were mostly abandoned except for the farms and vineyards that had sprung up among the ruins and for the churches and monasteries scattered among the ruins, most prominently the Lateran in the far southeast of the walled city, which until the 15th century was the seat of the Papacy; an area known as the disabitato.

The city that emerged from the Gothic Wars was also different in another way, it was Christian, completing a transformation starting in the 4th century. Although nominally ruled by the Byzantines until the mid-8th century, the city was actually governed by the popes, and, indeed, without their presence it is conceivable the city could have been completely abandoned, though there were still occasional visits by imperial dignitaries. In 608 the Byzantine Emperor Phocas came and a column was set up in his honor in the Forum, the last such monument to be placed there. The Emperor Constans II visited in 667 and one of his retinue carved the emperor's name inside the Column of Trajan.

Almost all new construction during this period was Christian - churches, monasteries, convents. A year after the visit of Phocas a temple was Christianized becoming the church of S. Maria Rotunda - the Pantheon built during the reign of Hadrian (117-138) - allowing this building with its remarkable architectural and structural aspects to be preserved relatively intact into the modern era. Likewise, the Column of Trajan, was saved for posterity in 1162 when it was placed under the protection of the Senate to ensure the column would "remain whole and undiminished as long as the world lasts"; which it has except for the substitution of the figure of St Peter in place of Trajan at the top of the column.

Below, the Pantheon, flooded in 1800, drainage in the city was still not as good as during the Roman empire. From Krautheimer

Column of Trajan and ruins of Trajan's Forum. The monstrosity to the right and behind is the Victor Emmanuel monument, built in the early 20th century to in honor of Italy's first king after reunification in 1870. (Photo from National Geographic)

The first systematic steps towards urban recovery occurred during the papacy of Gregory the Great (590-604). Some repairs were undertaken, the major streets and plazas were kept open and a few of the aqueducts and baths still functioned. The Forum of Trajan still saw some use and the former imperial palaces on the Palatine kept in some semblance of repair, though unused.

It was probably Gregory who restarted a scaled down version of the old imperial welfare offices in the city at which food was doled out at the start of each month. These centers, known as diaconiae, were scattered throughout the city with financial support coming from landholding set aside by the Church or from wealthy donors. The diaconie also served another audience, providing shelter and hospital services to the increasing number of religious pilgrims who visited the city beginning in the latter part of the 6th century, and whose numbers greatly increased during the 7th and 8th centuries. Krautheimer describes them:

The largest number came from among the peoples recently converted in the West. Franks, Irish and English, joined in the eighth century by Frisians and South Germans, struggled over the Alpine passes on foot or horseback . . . Hostels were set up in Provence and North Italy to shelter them on the road . . .The pilgrims consisted of bishops, clergy, monks and nuns, nobles and "ordinary folks in large numbers" making the perilous journey. Most only made the journey once. During the mid-9th century one of the child pilgrims was the young boy who became Alfred the Great, King of Wessex and victor over the Vikings.

The Basilica of Constantine & Maxentius, Giovanni Piranesi, 18th century. Ruins of the last large structure built in the Forum (4th century). From Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Despite becoming a religious center, the city remained poor and struggling. Though the Byzantine Empire lost its eastern and North African provinces to the followers of Muhammed in the 7th century it simultaneously attempted to assert control of Rome and its remaining Italian possessions. The city saw an influx of Greek refugees from the lost eastern provinces, and for a century an almost unbroken line of Greeks and Syrians served as popes.

Tensions were arising. A new class of local Rome landholders arose who objected to increasing Byzantine taxation, while an enormous rift opened between Rome and Constantinople over the abolition of images, iconoclasm, which had been decreed in the East. The final element was the renewal of efforts by the Lombards to crush the Byzantines. In 751 the Lombards captured Ravenna, the Byzantine capital of Italy, and in 753 laid siege to Rome. Realizing the enfeebled eastern empire could not provide help, Pope Stephen II appealed to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks, who intervened, saving the city. Twenty years later, when the Lombards tried once again to attack Rome, Pope Hadrian I sought help from Pepin's son, Charlemagne, who in 774 invaded Italy, crushed the Lombards, and ended their kingdom. In 800, the Pope crowned Charlemage as Emperor of the West and of what became known as the Holy Roman Empire. For the next three centuries there ensued a constant struggle for control of Rome between the Holy Roman emperors, the popes and the most powerful families within the city.

The wars of the late eighth century caused additional damage to Rome and its environs.

Once again, estates outside the walls, private and Church property, were looted and burned, country folk and monastic congregations were driven into the city . . . The aqueducts, neglected and partly destroyed in the Lombard sieges, functioned badly or not at all . . . time and again the Tiber flooded the town and the fields across the river [the flood control structures of the Roman empire had long ago decayed] . . . buildings were in poor repair.A new threat arose in the early 9th century. After completing the conquest of North Africa in 698, Moslems invaded Sicily early in the 9th century. They also began raiding the Italian mainland, in 846 looting the churches of Saints Peter and Paul, which at the time lay outside the walls of Rome and the threat continued into the early 10th century.

What was it like to be in Rome during those centuries? As Krautheimer notes, after the Gothic War "Rome had become a rural town, dependent on agricultural produce close at hand"; when the Tiber flooded, famine ensued and the crumbling ancient drainage systems led to malaria becoming endemic. The populace huddled against the river with the ruins of the imperial city surrounding them. Ancient structures like the Theaters of Pompey and Marcellus were converted into crowded housing or small market stalls, others were dismantled for their valuable exteriors, marble or bronze, or stripped for other construction (Emperor Constans had offended Romans when during his visit in 667 he removed the bronze tiles from the Pantheon and shipped them to Constantinople).

Theatre of Marcellus with shops in 1880. From Krautheimer

More ancient monuments and buildings lay further afield in the disabitato. Rome had:

no need to search for the remains of antiquity. They were ever present: the Pantheon, the Colosseum . . . the ruins of the great thermae and of the palaces of the Palatine; the remains of the temples on the forum and the Campus Martius, the forums themselves, those of Nerva, Augustus, Trajan; the triumphal arches and the monumental columns of Marcus Aurelius and Trajan, the mausolea of Hadrian and Augusuts, the obelisks . . . Ancient sculpture, too, was plentiful: the reliefs on the triumphal columns and arches . . . Wall paintings, mosaics, and stucco decoration must have been accessible in the ruins of the Golden House, on the Palatine, in the vaults of the Colosseum - many lost to us but surviving in their medieval reflections.After the turmoil of the 9th and 10th centuries, large scale building activity resumed. As Krautheimer points out, while not a commercial center, Rome:

The hoi polloi of Romans and visitors, especially pilgrims, would be overwhelmed by the sheer size of a building or a colossal statue surviving in fragments and spin strange yarns about it . . .

had developed resources of a different kind: the vast income of the Church . . . the swollen bureaucracy of the Curia; the city's place as the foremost legal center of Europe with lawyers, clerks, and scribes attracting business; the flux of pilgrims . . . the banking operations of and connected with the ChurchThis revival, unlike the earlier ones, was sustained and by 1527, when the first real census was undertaken, the population had risen to 55,000. It was also in these centuries that most of the damage to the structures of ancient Rome occurred. Krautheimer describes the city of those centuries as:

. . . not so much as a coherent unit, but as a conglomerate of built-up clusters separated by large ruins, gardens, and stretches of wasteland, with only scattered houses linking the clusters.Settlement in 13th century Rome. You can see how little of the area within the walls is urbanized. (From the Mendicant Revolution)

The accelerated pace of building took place within the established clusters of settlement and created increased demand for building materials. Remaining marble cladding was removed from the old buildings and the buildings themselves disassembled to provide materials for new construction. Some structures had almost completely disappeared. The vast Circus Maximus, pictured near the beginning of this post in all its glory, lay in a valley between the Palatine and Aventine hills. Much of its structures was removed and Once drainage systems were no longer maintained it became vulnerable to flooding from the Tiber; repeated inundations over the centuries left a thick layer of mud over the entire site, which remains 20 to 30 feet below the surface.

Flooding also affected the low lying Forum. The accumulated mud eventually became a grazing area for cattle with only the tops of monuments peeking above ground until excavation of the area began in the 19th century.

Below, Arch of Septimius Severus in the Forum showing inundation by Claudio Lorense (1650)

The same area in 1575 with a defensive tower built on top of the arch. The Roman senate house is to the right. From Krautheimer.

Below, the disabitato south of the Colosseum still existed in 1870. Today this area is entirely urbanized. From Krautheimer.

What would have it been like to walk around the city in the year 1000? You'd see some structures already in ruins, or, if in low lying areas, mostly covered in mud. Other buildings would still have their marble cladding, perhaps damaged or partially covered by plant growth. Much of the statuary, now damaged or lost, was still relatively intact. The Stadium of Domitian (built in the 1st century) still existed though crumbling, and its racing area remained open land. It was not till the 17th century that a large church was built and the open area converted into the grand piazza that we see today. From an aerial view (below) you can still see the layout of the ancient stadium and track.

The Colosseum was not the partly dismantled wreck it is today; the arena floor had been converted into a cemetery and the arcades under the seating had been converted into workshops and housing. It was not until after an earthquake 1349 that parts of the massive structure were removed for use elsewhere in the city. It was only saved from further use as a quarry by order of Pope Benedict XIV who in 1749 designated it as a sacred site because of the martyrdom of early Christians in its arena. Seeing these buildings, statues and monuments would evoke a sense of wonder in us - and of what had been lost - what did those who lived there in those centuries think?

This is a wonderful blog and I'd like to inform the creator that I have shared a couple of photos and the blog's entire URL with Facebook friends and interested parties...with full CREDIT to this page. Sol

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed it. Take a look at my other posts with Rome tag as you may also like.

Delete