Originally posted in 2015 and intended as a meditation on how history is remembered or misremembered rather than a discussion of evolutionary theory. At the time I wrote it there were still some efforts to insert creationism into public school curriculum. That effort seems to have ceased, but evolutionary biology now appears under assault from different quarters so thought I'd repost with some edits.

Rather than the often

repeated adage that the victors write the history of an event, the story

of anything is actually determined by the unswerving adoption of one

version of it, and the telling of that version by a determined cadre of

writers. In time, the version with the most persistent adherents becomes

the “truth.” – David & Jeanne Heidler in Henry Clay: The Essential American (2010)

I

still recall the family getting in the car for the drive to

Hartford, Connecticut. It was the late 1950s, and my father was taking

us to pick up a monkey. He had a small role as an Italian

organ-grinder in a play put on by a local community theater group. The

director wanted to use a prop monkey, but dad insisted on the real

thing. We housed that monkey for the next week; I remember it as nasty

and mean-tempered, but the audience loved it as well as dad in his bit

part (he always had a knack for showmanship). The play was

Inherit The Wind, based on a 1925 event in Tennessee that became popularly known

as the Scopes Monkey Trial.

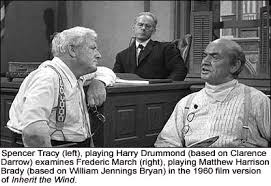

Seeing the play and, later, the movie, I accepted its narrative of

the forces of enlightenment, reason, heroism, and tolerance (represented

by

Spencer Tracey in the movie, playing a character based on

Clarence

Darrow) against the forces of narrow-mindedness, mean-spiritedness,

repression, and unthinking old-fashioned religion (represented by

Frederic March playing a character based on

William Jennings Bryan); a

morality play of liberal versus conservative written during the McCarthy years. The play is still staged

frequently by regional theaters (here’s a recent

Wisconsin production), has gone through several Broadway revivals, most recently

in 2007,

with Christopher Plummer and Brian Dennehy. There was even a London

production, in 2009, with Kevin Spacey. In most cases, it is widely

accepted by audiences as historically accurate.

It was only years later, prompted by reading

Edward Larson’s Summer For The Gods

and doing related research that I appreciated how much more complex and

interesting the real story was. American history is much more

fascinating and instructive when you don’t try to neatly shoehorn it

into boxes labeled “liberal,” “conservative,” “progressive,” and

“reactionary” as

Inherit The Wind did, aided by influential

mid-20th century historians and literary critics such as Richard

Hofstadter. Throughout our history, you’ll see prominent people with constellations of political views that are unrecognizable in today’s

categories (see

Sam Houston as an example). I support the teaching of evolutionary theory but the

full story behind the Scopes Trial is more interesting than the

caricature of

Inherit The Wind and, as I learned, the main character in this drama, William

Jennings Bryan, would not neatly fit into any political classification

in modern-day America.

The Background

Dayton in 1925

The early 20th century saw an explosion in the growth of public high

schools. In 1890, there were fewer than 200,000 public high-school

students nationwide; by 1920, more than two million. In

Tennessee, fewer than 10,000 in

1910, but more than 50,000 by 1920. What were they to be taught?

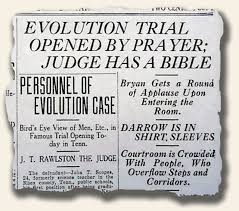

At the same time, battles were heating up between Darwinists and some

religious denominations over the teaching of evolution. State

legislative fights over its inclusion in educational curriculum became

common.

Legislative efforts barring the teaching of evolutionary theory were

successful in a small number of states, including Tennessee, which

passed its law in early 1925. It was part of a larger package of

laws in a massive education reform bill that laid the foundation for

state-supported public schools. It was signed into law by progressive

Governor Peay. Violation of the ban on teaching evolution carried a $100

fine, but no jail. Bryan supported the bill, but unsuccessfully lobbied

against having any fine attached to violating the evolution provision,

though no one at the time expected any prosecutions under the statute.

John Scopes

Looking for a test case, the American Civil Liberties Union placed

advertisements in Tennessee papers offering to defend anyone prosecuted

under the Act. Leading citizens of the town of Dayton decided to take

them up on it. While some were interested in challenging the law, many

others just saw it as a good opportunity to create publicity and

generate business for the town. Rather than showcasing a contentious,

divided populace, as portrayed in the play, the actual trial took place

in a festive atmosphere, according to reporters like H.L. Mencken. The

key players in Dayton recruited John Scopes, a young, part-time

schoolteacher, to be the defendant and agreed to pay any penalty imposed

on him.

Dayton was a small town in East Tennessee, and part of the only

Republican enclave in the state. Bryan won every southern state in each

of his three presidential runs, but never carried Rhea County

where Dayton was located. The town was also heavily Methodist in a state

dominated by Baptists (the Baptist Convention, meeting in Memphis just

before the trial, refused to add an anti-evolution plank to the

denomination’s statement of faith).

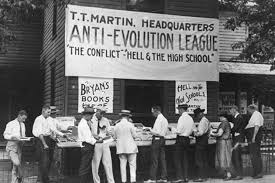

Once the ACLU came into the case, Bryan — the country’s leading

opponent of the teaching of evolution — agreed to become part of the

prosecution’s team. And through some very complicated machinations,

Clarence Darrow, the most famous criminal defense lawyer in America,

joined the defense team. When this happened, the trial became the

biggest story in the country, and was also followed heavily in Europe. A

deluge of reporters descended on Dayton.

Why Evolution? Why Bryan?

In

1925, 65-year-old William Jennings Bryan was well known to every

American, having run unsuccessfully three times as the Democratic

Party’s presidential candidate (1896, 1900, and 1908). A remarkable

orator — his “

Cross of Gold” speech at the 1896 convention

secured him the nomination — he is considered to be the first

populist to run for President. In 1913,

Woodrow Wilson appointed him

Secretary of State, a post he resigned in 1915 when the pacifist Bryan

became convinced Wilson was maneuvering the country into entering the

First World War.

Bryan campaigned successfully

in support of four

constitutional amendments: direct election of senators, the Federal

income tax, women’s suffrage, and Prohibition. He certainly doesn’t

sound like a man who fits the image created by

Inherit The Wind.

So why, in the 1920s, did he undertake leadership of the crusade

against the teaching of Darwinism, and why did he think it was

consistent with his other views?

Bryan believed in

“

popular sovereignty" and had always campaigned against big business

and the banks and on behalf of the common people. When the Supreme Court

overturned some of the early progressive labor laws, Bryan supported

(unsuccessful) legislation to limit judicial review, and backed the

Progressive use of popular referendums. He believed the people were

entitled to what they wanted, and he saw the evolution issue in the same

way. According to Bryan:

It is no infringement on their freedom of

conscience or freedom of speech to say that, while as individuals they

are at liberty to think as they please and say what they like, they have

no right to demand pay for teaching that which parents and the taxpayer

do not want taught.

The

deeper reason was Bryan’s concerns about the implications of Darwinism.

Bryan was a committed Christian and pacifist. He rejected evolutionary theory as a matter of

religious faith, but also believed Darwinism and its doctrine of

“

survival of the fittest” threatened the dignity and perhaps even the

very existence of the weakest of the human flock. Bryan saw a direct

connection between the excesses of capitalism and militarism — which he

had denounced throughout his career — and Darwinism, which, as early as

1904, he had called “

the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and

kill off the weak.”

The concerns Bryan raised in 1904 were reinforced by recent events.

The slaughter of WWI appalled Bryan. He saw German militarism as

Darwinian selection in action; this was a common view at the time, as

reflected in the words of Vernon Kellogg in his book

Headquarters Nights: “

Natural selection based on violent and fatal competitive struggle is the gospel of the German intellectuals.”

Bryan saw the modernist wing of the Progressives, led by Woodrow

Wilson, as willing to go down this same road. It is striking to see how

much Darwinism was in the air of politics at the time.

Wilson’s key 1912 campaign speech, “

What is Progress?” espoused a

Darwinian approach to American government:

Now, it came to me, as this interesting man talked, that

the Constitution of the United States had been made under the dominion

of the Newtonian Theory. You have only to read the papers of the The

Federalist to see that fact written on every page. They speak of the

“checks and balances” of the Constitution, and use to express their idea

the simile of the organization of the universe, and particularly of the

solar system — how by the attraction of gravitation the various parts

are held in their orbits; and then they proceed to represent Congress,

the Judiciary, and the President as a sort of imitation of the solar

system. …

Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure

and in practice. Society is a living organism and must obey the laws of

life, not of mechanics; it must develop. All that progressives

ask or desire is permission — in an era when “development” “evolution,”

is the scientific word — to interpret the Constitution according to the

Darwinian principle; all they ask is recognition of the fact that a

nation is a living thing and not a machine. [emphasis added]

The new science of eugenics troubled Bryan. The high school textbook used by John Scopes was

A Civic Biology

by George William Hunter, in which he defined eugenics as “

the science

of improving the human race by better heredity.” Hunter wrote,

If such people were lower animals, we would

probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading … Humanity will

not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in

asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and

the possibility of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.

The prior edition of Hunter’s textbook had contained language specifically citing biological deficiencies of African races.

Eugenics had many scientist adherents in the United States and

England who believed that the human race could be made better via

selective breeding to create a better and more progressive world. One of

those scientists, A.E. Wiggam, expressed the connection between the

teaching of evolution and eugenics:

“until we can convince the common man of the fact of

evolution … I fear we cannot convince him of the profound ethical and

religious significance of the thing we call eugenics.”

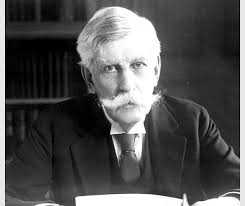

Holmes

During the 1920s and 30s, the eugenics movement gained momentum. By

1935, more than 30 states had laws mandating sexual segregation and

sterilization of persons regarded as eugenically unfit. The most

notorious expression of support for eugenics came in 1927 from the

leading Social Darwinist on the Supreme Court,

Oliver Wendell Holmes,

Jr., who in his opinion for the Court upholding Oklahoma’s sterilization

law wrote, “

three generations of imbeciles is enough.” The only

dissenting vote was cast by

Pierce Butler, the lone Catholic on the

Court.

Within a few years, WWII and the revulsion against Nazi law and

experimentation would put an end to the eugenics movement (though a

revival of eugenics under another name is conceivable with modern

advances in biology and genetics). The heyday of both the eugenics

movement and the rise of anti-evolutionary forces led to the Dayton

trial in 1925. Bryan expressed his pithy view of the whole matter when

commenting on the latest discovery of purported early human remains:

“

Men who would not cross the street to save a soul have traveled across

the world in search of skeletons.” In his closing argument at trial, Bryan put it this way regarding evolutionary theory:

". . . if taken seriously and made the basis of a philosophy of life, it

would eliminate love and carry man back to a struggle of tooth and

claw."

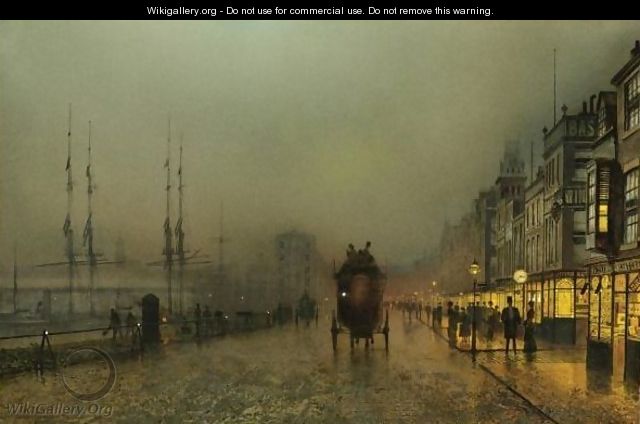

By John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-93). Until recent years, the English artist had languished in obscurity as his reputation declined after the Victorian era. Today he is regarded as one of the finest nightscape and townscape painters.

By John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-93). Until recent years, the English artist had languished in obscurity as his reputation declined after the Victorian era. Today he is regarded as one of the finest nightscape and townscape painters.

and if you are walking from the Forum through the arch you will be looking at the Colosseum, built in part with the labor of Jewish slaves captured in that war (66-70 AD). The Emperor Hadrian (117-38 AD), a devotee of Hellenism and enemy of the Jews, decreed a temple honoring the gods of Rome should be placed on the vacant Temple Mount as a demonstration of Roman power, a decree that prompted one final great revolt, finally suppressed after three years, resulting in the banishment of all Jews from Jerusalem and the surrounding area and changing the name of the province from Judea to Palestine. Starting in the 4th century the Eastern Roman emperors placed increasing restrictions on Jewish life in Palestine, until finally in the aftermath of the great

and if you are walking from the Forum through the arch you will be looking at the Colosseum, built in part with the labor of Jewish slaves captured in that war (66-70 AD). The Emperor Hadrian (117-38 AD), a devotee of Hellenism and enemy of the Jews, decreed a temple honoring the gods of Rome should be placed on the vacant Temple Mount as a demonstration of Roman power, a decree that prompted one final great revolt, finally suppressed after three years, resulting in the banishment of all Jews from Jerusalem and the surrounding area and changing the name of the province from Judea to Palestine. Starting in the 4th century the Eastern Roman emperors placed increasing restrictions on Jewish life in Palestine, until finally in the aftermath of the great  (From Astronomy Picture of the Day)

(From Astronomy Picture of the Day)