/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/86/9e/869e5471-35d5-4ec7-b88f-ab8566d82207/julaug2024_g99_berenike.jpg) Last year Smithsonian Magazine carried an article on the recent excavations at the Ptolemaic port of Berenike on the Red Sea, the Egyptian end of the sea trade with India, which have revealed more about the depth of the connections between the two regions.

Last year Smithsonian Magazine carried an article on the recent excavations at the Ptolemaic port of Berenike on the Red Sea, the Egyptian end of the sea trade with India, which have revealed more about the depth of the connections between the two regions.

Though the port was founded by the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty (320-30 BC), the trade was greatly expanded after Rome annexed Egypt in 30 BC. THC wrote about this trade and the farthest reaches of the Roman Empire in The Farthest Outpost. It's not just the extent of the trade and the navigation skills and knowledge needed for it, but the logistics of building an isolated port on the Red Sea, separated from the rest of Egypt by a vast desert requiring the establishment and maintenance of a safe and secure land-based transport system.

From the Smithsonian article:

In antiquity, this site, known as Berenike, was described by chroniclers such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder as the Roman Empire’s maritime gateway to the East: a crucial entry point for mind-boggling riches brought across the sea from eastern Africa, southern Arabia, India and beyond. It is hard to imagine how such vast and complex trade could have been supported here, miles from any natural source of drinking water and many days’ arduous trek across mountainous desert from the Nile. Yet excavations are revealing that the stories are true.

Archaeologists led by Steven Sidebotham, of the University of Delaware, have revealed two harbors and scores of houses, shops and shrines. They have uncovered mounds of administrative detritus, including letters, receipts and customs passes, and imported treasures such as ivory, incense, textiles, gems and foodstuffs such as pots of Indian peppercorns, coconuts and rice. The finds are not only painting a uniquely detailed picture of life at a lesser-known but critical crossroads between East and West. They are also focusing scholarly attention on a vast ancient ocean trade that may have dwarfed the terrestrial Silk Road in economic importance and helped sustain the Roman Empire for centuries.

“All the ancient sources talk about this place,” he says. One Greco-Roman text, known as the Periplus Maris Erythraei, or “Voyage around the Erythraean Sea”—which Bhandare, of Oxford, described as “a kind of Lonely Planet guide for the first century A.D.”—lists the port as a hub for maritime trade routes stretching south as far as modern-day Tanzania, and east, past Arabia, to India and beyond. But Berenike’s location was lost for centuries, until the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni, after nearly perishing from thirst in the search, rediscovered it in 1818 and hired a Bedouin youth to dig in the Isis temple with a giant seashell. A handful of European and American travelers followed, but the entire area fell back out of reach for decades, designated off-limits by an Egyptian army keen to control the coastline close to Sudan.

And as archaeologists are busy analyzing the growing material finds, other scholars are reassessing literary sources to better evaluate the economic impacts of these intercontinental networks. They already knew that trade was robust. In the early first century A.D., before trade reached its peak, the Greek geographer Strabo described eastbound fleets of more than 100 merchant ships. Another key source, a contract known as the Muziris papyrus dating from the second century, is more specific, describing a loan between an Alexandria-based businessman and a merchant for a return voyage to Muziris. On the reverse side, the text details the cargo of a ship called the Hermapollon, which included 140 tons of pepper, 80 boxes of nard (an aromatic oil used for perfumes, medicines and rituals), and around four tons of ivory. Its value, after payment of the Roman Empire’s 25 percent import tax, was nearly seven million sesterces, which scholars have calculated was easily enough to buy a luxury estate in central Italy, or, if you prefer, to pay 40,000 stonecutters for a year. That translates into some vast fortunes.

The island of Socotra, mentioned in the article, is also the subject of a THC post.

Berenike today:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/46/cf460e49-7920-44a1-8476-44c5c0c44f2c/julaug2024_g06_berenike.jpg)

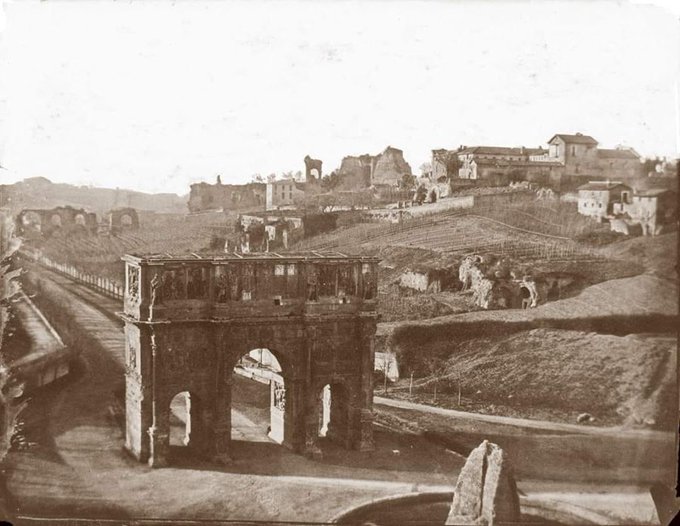

Comparing the two pictures you can see the dramatic difference after the flood sediment and debris were removed during the 19th century. In the painting the top of the arch on right is barely visible, while the photo shows the arch fully revealed. Examining the height of the people around it, the sediment was 10-15 feet deep.

Comparing the two pictures you can see the dramatic difference after the flood sediment and debris were removed during the 19th century. In the painting the top of the arch on right is barely visible, while the photo shows the arch fully revealed. Examining the height of the people around it, the sediment was 10-15 feet deep.

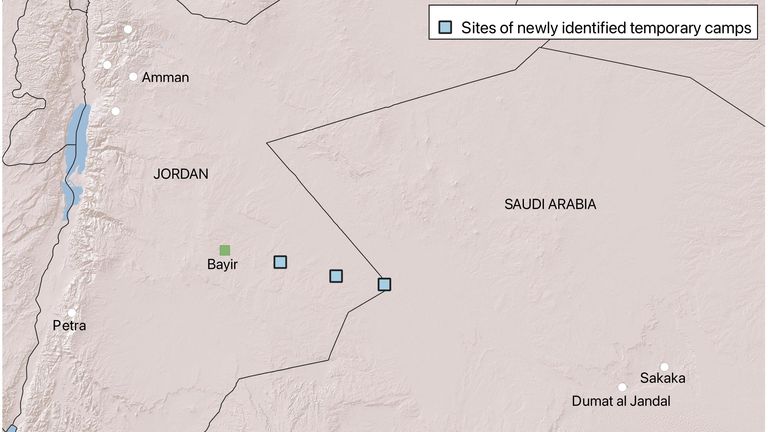

Three previously unknown Roman forts have been identified in the bleakness and isolation of the Arabian Desert. First located via Google Earth, they are in the southeast part of present-day Jordan, adjacent to Saudi Arabia. As reported in

Three previously unknown Roman forts have been identified in the bleakness and isolation of the Arabian Desert. First located via Google Earth, they are in the southeast part of present-day Jordan, adjacent to Saudi Arabia. As reported in

and if you are walking from the Forum through the arch you will be looking at the Colosseum, built in part with the labor of Jewish slaves captured in that war (66-70 AD). The Emperor Hadrian (117-38 AD), a devotee of Hellenism and enemy of the Jews, decreed a temple honoring the gods of Rome should be placed on the vacant Temple Mount as a demonstration of Roman power, a decree that prompted one final great revolt, finally suppressed after three years, resulting in the banishment of all Jews from Jerusalem and the surrounding area and changing the name of the province from Judea to Palestine. Starting in the 4th century the Eastern Roman emperors placed increasing restrictions on Jewish life in Palestine, until finally in the aftermath of the great

and if you are walking from the Forum through the arch you will be looking at the Colosseum, built in part with the labor of Jewish slaves captured in that war (66-70 AD). The Emperor Hadrian (117-38 AD), a devotee of Hellenism and enemy of the Jews, decreed a temple honoring the gods of Rome should be placed on the vacant Temple Mount as a demonstration of Roman power, a decree that prompted one final great revolt, finally suppressed after three years, resulting in the banishment of all Jews from Jerusalem and the surrounding area and changing the name of the province from Judea to Palestine. Starting in the 4th century the Eastern Roman emperors placed increasing restrictions on Jewish life in Palestine, until finally in the aftermath of the great

This animated video below provides an entertaining and instructive guide to how the tunnel, which may have provided water for a thousand years, was designed and constructed.

This animated video below provides an entertaining and instructive guide to how the tunnel, which may have provided water for a thousand years, was designed and constructed.