Archibald Wright Graham died on this date, sixty years ago in Chisholm, Minnesota. Graham, better known to most as Moonlight and in Chisholm as Doc, came to wide attention as a character in WP Kinsella's novel Shoeless Joe, and the 1989 film based on his book, Field of Dreams.

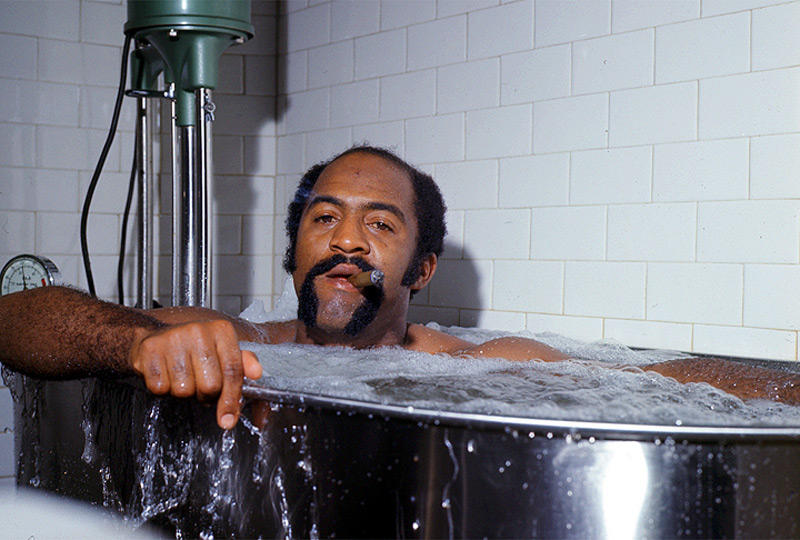

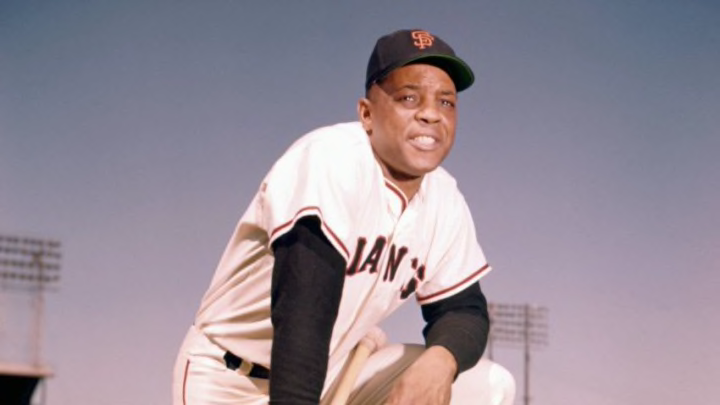

(Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, from wikipedia)

(Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, from wikipedia)

I recently caught Field of Dreams on TV.

It remains highly rewatchable. If you haven't seen it, I won't

describe the plot because it makes the movie sound ridiculous, while it

is really wonderful (and ridiculous at times). The last scene always moves me. And it is about much more than baseball.

I already knew that

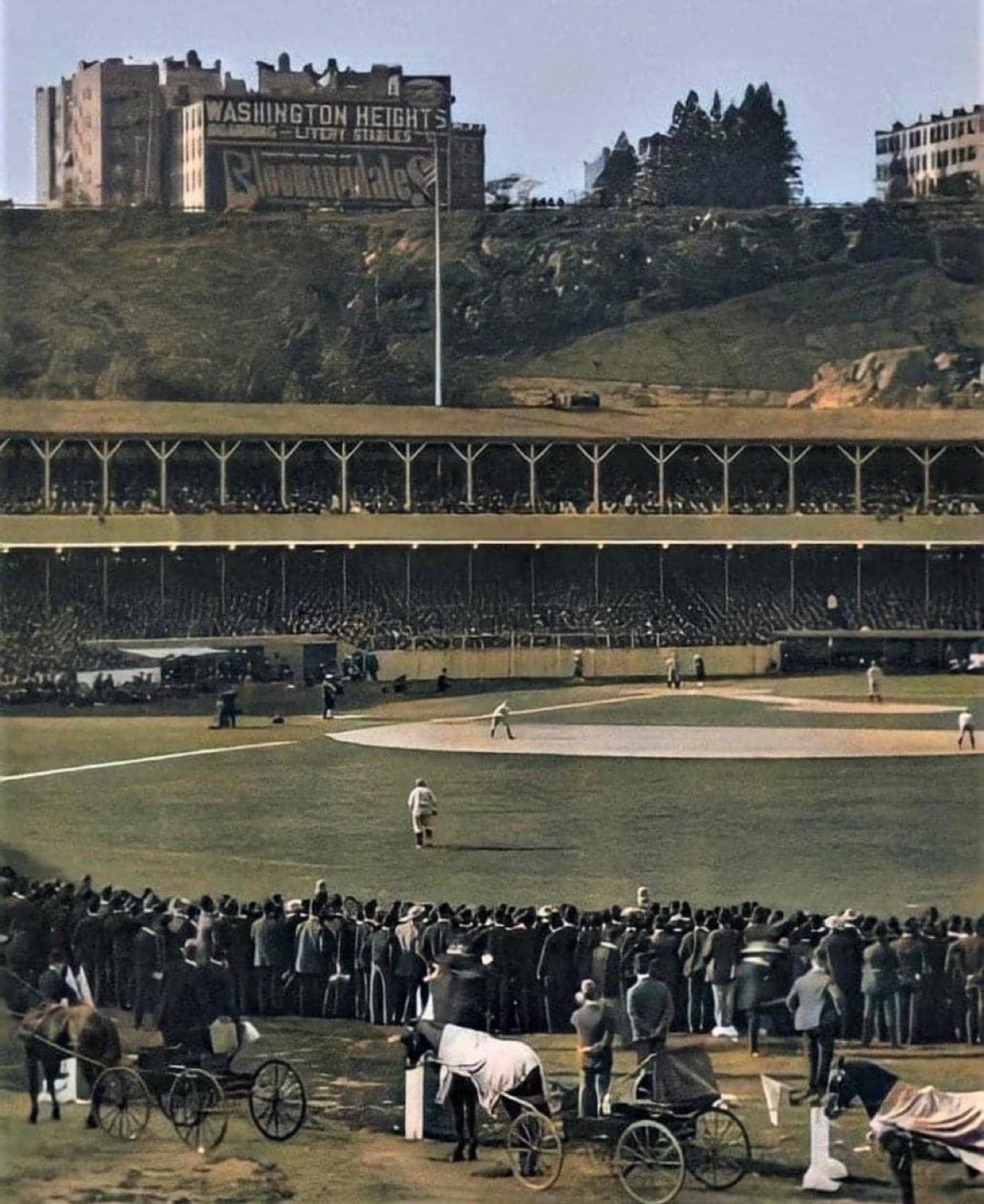

the real Archie Graham played in the outfield for two innings in a June

1905 game after being called up from the minors to join John McGraw's

New York Giants. It was his only major league appearance and he never got a chance to bat. Graham (Burt Lancaster) tells the story in Field of Dreams. In the 1970s, author WP Kinsella ran across a mention of Graham while perusing the Baseball Encyclopedia, was captured by his brief career and nickname, and included him as a character in Shoeless Joe. Graham reportedly garnered the nickname Moonlight because he was "fast as a flash".

What I had not realized was how closely the fictionalized version of

Moonlight Graham in the book and movie was to the real Archibald Graham.

In the movie, Graham's one appearance with the Giants takes place in

1922. He later retires from baseball and moves to Chisholm, Minnesota,

becoming a doctor and dying in 1972. Doc Graham, as he is known, is a

beloved figure in that small town, with a sterling reputation, and

devoted to his wife Alicia, who always wears blue. Doc always walks

with an umbrella. In one scene, Terrence Mann (James Earl Jones)

interviews older townsfolk about Doc Graham and they tell endearing

stories of him. Terrence and Ray Kinsella (Kevin

Costner) also go to the local newspaper where a reporter reads to them from

Doc Graham's obituary.

It turns out the real Archibald Graham was a college graduate, unusual

in baseball in those days, and received his medical degree from the

University of Maryland in 1905, the same year he played for the Giants. After a couple of more years in the minor leagues he moved to Chisholm in 1909, because he was suffering from a respiratory condition and heard the climate in the Iron Range mining town could help him. The town immediately to the south of Chisholm is Hibbing, where Robert Zimmerman (Bob Dylan) grew up. Graham opened a medical practice, a few years later becoming the school system doctor, a role he remained in until 1960, along with being the team doctor for all of the school sports teams. He married Alicia Madden, who always wore blue,

and he always carried an umbrella. Doc Graham died in 1965 and Alicia in 1981. The

anecdotes used in the movie are from the life of the real Graham, and

the reporter in the film is reading from his actual obituary.

From the Chisholm Free Press & Tribune (1965)

"And there were times when children could not afford eyeglasses or milk or

clothing. Yet no child was ever denied these essentials because in the

background there was always Dr. Graham. Without any fanfare or publicity,

the glasses or the milk or the ticket to the ballgame found their way into

the child's pocket." [This was the portion read in Field of Dreams]

From a 2005 article in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune:

While still new in Chisholm, he grew sweet on Alicia Madden, a

schoolteacher. She was a farmer's daughter from Rochester, and they married

in 1915.

They never had children. Instead, they showered their affection on every

child in town -- he as the full-time doctor for the public schools for more

than 40 years, she as the director of countless community plays.

They built a house that still stands in southeast Chisholm, on the fringe of

a neighborhood known as Pig Town, for the livestock kept by the hardscrabble

immigrant miners' families.

"That was Doc," said Bob McDonald, who grew up in Chisholm and has coached

high school basketball there for 44 years. "He and Alicia could have lived

up with the high and mighty on Windy Hill, but they chose to be among the

common people."

McDonald remembers a wiry, athletic man, dapper in an ever-present black hat

and black trench coat, walking everywhere and always swinging an umbrella.

Yes, he said, Alicia did always wear blue.

On the opening night of all of her plays, Graham would sit in the same seat

in the back of the high school auditorium, a dozen roses in his lap,

Ponikvar said.

People were poor, but schools used mining company taxes to meet needs. Under

Doc's care, kids got free eyeglasses, toothbrushes and medical care. He

lectured them on nutrition, inoculated them, rode their team buses, made

20-year charts of their blood pressure, swabbed their sore throats, made

house calls if they stayed home sick.

He bought apartment houses but charged rock-bottom rents, and no rent to a

single mother and her eight children, Ponikvar remembers.

"Doc became a legend," she wrote when he died. "He was the champion of the

oppressed. Never did he ask for money or fees."

Below is a preview (narrated by Vin Scully!) of a Mayo Clinic film about Doc Graham's collaboration with the clinic on a groundbreaking study of blood pressure in children.

(Lou Brissie)

(Lou Brissie) (Phil Marchildon)

(Phil Marchildon)

(Ruth, on right)

(Ruth, on right)