Today is the anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy but instead of writing about that, let's go back to darker days two years earlier.

In early 1942 Japan rampaged across the Pacific and South Asia. Islands in the central Pacific, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies and Burma had all been occupied, Imperial Army troops had recently landed on New Guinea, and the Imperial Navy fleet ranged as far as the Indian Ocean, raiding Ceylon and bombing cities on the coast of India, and even struck Australia, raiding Darwin on the north coast.

To Japan's surprise the American and Filipino forces in the Philippines posed tough resistance, holding out on the Bataan Peninsula until April 9, when weakened by disease and malnutrition (the average soldier had lost a 1/3 of their body weight) surrender became the only option. The prisoners then embarked on the horror of the Bataan Death March during which thousands were shot, bayoneted or beheaded by the Japanese before reaching the prison camps where thousands more were to die.

That left the final American and Filipino stronghold - the tiny island of Corregidor, off the coast of Bataan with 13,000 military personnel under the command of General Jonathan Wainwright. All knew there was no hope of rescue and only a matter of time before the Japanese assault.

On May 3 the Japanese began the artillery bombardment of the island, landing troops two days later. Wainwright's command post was in the Malinta Tunnel near the center of the island. As the Japanese attack continued the tunnel also filled with dead, wounded and those seeking a place of refuge from the shelling. By the next day the situation was hopeless and Wainwright agreed to surrender.

(Malinta Tunnel before Japanese attack)

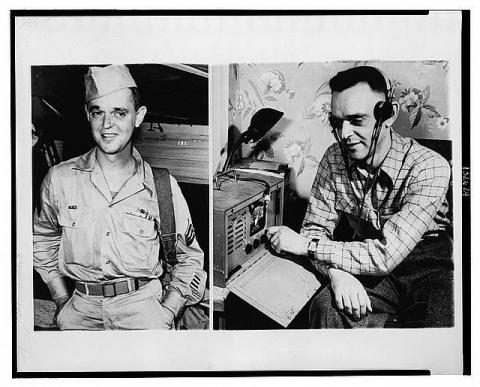

In the Malinta Tunnel was radio operator Cpl. Irving Strobing, a 22 year old from Brooklyn who'd enlisted in 1939. During the last 90 minutes before the capitulation became official, Strobling sent a stream of Morse Code messages that, when transcribed, were over the next few months broadcast and reprinted across America. The personal nature of them, mixing humor, horror, and emotion, struck a chord with listeners.

Here are some of the messages:

We are waiting for God only knows what. How about a chocolate soda?

The jig is up. Everyone is bawling like a baby. They are piling dead and wounded in our tunnel. I'm vomiting. Arm's weak from pounding key, long hours, no rest, short rations, tired.

Corregidor used to be a nice place. Haunted now.

Hey, I have 60 pesos you can have for the weekend.

General Wainwright is a right guy and we are willing to go on for him, but shells were dropping all night, faster than hell. Damage terrific. Too much for guys to take.And then came his final transmission:

My name is Irving Strobing. Get this to my mother, Mrs. Minnie Strobing, 605 Barbey Street, Brooklyn, N.Y. They are to get along OK. Get in touch with them as soon as possible. Message, my love to Pa, Joe, Sue, Mac, Harry, Joy and Paul. Also to all family and friends. God bless 'em all. Hope they be there when I come home. Tell Joe, wherever he is, go give 'em hell for us. My love you all. God bless you and keep you. Love. Sign my name and tell my mother how you heard from me.There was a pause, then "Stand by," then nothing.

You can listen to a reading of Strobing's transmissions here.

Strobing's final message reached Secretary of War Henry Stimson and arrangements were made to have an Army Colonel personally deliver it to Minnie Strobing.

After the surrender, Strobing was imprisoned in a Phillipine POW camp. In November 1942 he was sent to Japan, spending 27 days in the hold of a transport ship (also known as Hell Ships) and then did hard labor, part of a group of prisoners excavating by hand a dry dock, stoking steel mill furnaces and, as he described it, making "little rocks out of big rocks", for the next 2 1/2 years before freedom arrived on September 5, 1945.

(The surrender, emerging from the tunnel)

In this radio interview, Strobing tells of the moment of surrender and of his time as a prisoner.

Returning to the U.S. he met the man who'd received and transcribed his transmissions in Hawaii, Sgt Arnold Lappert. Lappert, based at Schofield Barracks on Oahu, was responsible for passing messages to and from the Phillipines. After the fall of Bataan, Corregidor was the sole remaining transmission post in the Philippines and he and Strobing had gotten to know each other, discovering they were both New Yorkers (Lappert was from Manhattan). When they finally met in 1946 they had chocolate sodas together.

Leaving the Army in 1949, Strobing worked for the Federal Aviation Agency in New York and the Department of Agriculture in New Jersey. After retiring in 1980, he moved to North Carolina and became active in amateur radio clubs. He died in 1997 at the Veteran's Hospital in Durham, North Carolina. Arnold Lappert passed in 2007.

I came across this comment on one of the YouTube videos which reflected nicely on Mr Strobing.

I was fortunate enough to meet him when he was a ham radio operator in retirement in North Carolina--he was call sign N4FLW and I was N4NDK (now W1ST). A great and humble man, and my young son Will and I would often stop by his home for a friendly visit. He was always an avid radio operator and always had a significant modeling project underway across a table on his living room table. He would loan to me radio gear from time to time. He also always had a new plastic truck toy from the Hess Oil company to give to my son. I went to his funeral and met some of his family. I was amazed that they knew of me, from stories he would tell of the visits.Irving Strobing is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

GOD bless Mr. Strobing and all the brave men and women who served at Bataan and Corregidor. It was a miracle anyone lived through that nightmare to tell the story.

ReplyDelete