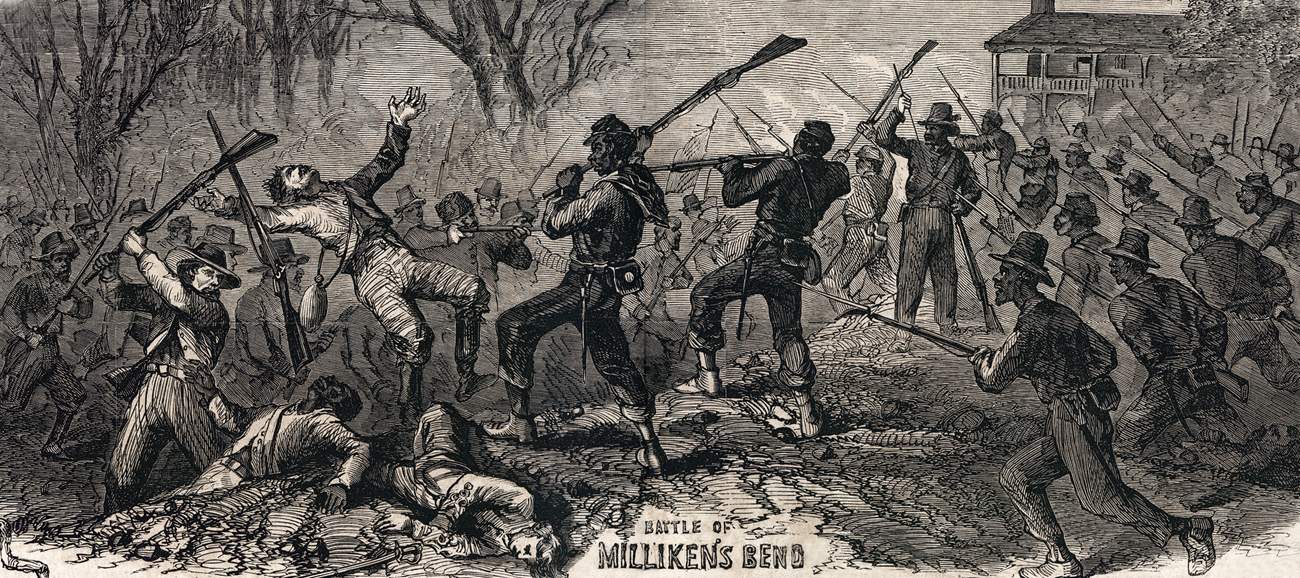

In June and July of 1863, three battles marked the first significant actions of the United States Colored Troops; Port Hudson (May 27), Fort (or Battery) Wagner (July 18), and Milliken's Bend (June 7). The latter was very different in its circumstances from the others. Port Hudson and Wagner both involved free blacks, free born Louisiana Creoles in the case of Hudson, and mostly New England free blacks in the case of the 54th Massachusetts assault on Wagner (an action depicted in the fine movie Glory). In contrast, the black soldiers at Milliken's Bend had been slaves just weeks before. Further, at Hudson and Wagner most of the Union soldiers involved in the battle were white, while at Milliken's Bend about 90% of the Federals engaged were black.

Last night our local Civil War Roundtable, for which I serve as program chair, had the pleasure of hearing a presentation by Linda Barnickel, author of Milliken's Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory, the first book-length treatment of the battle and one I highly recommend.

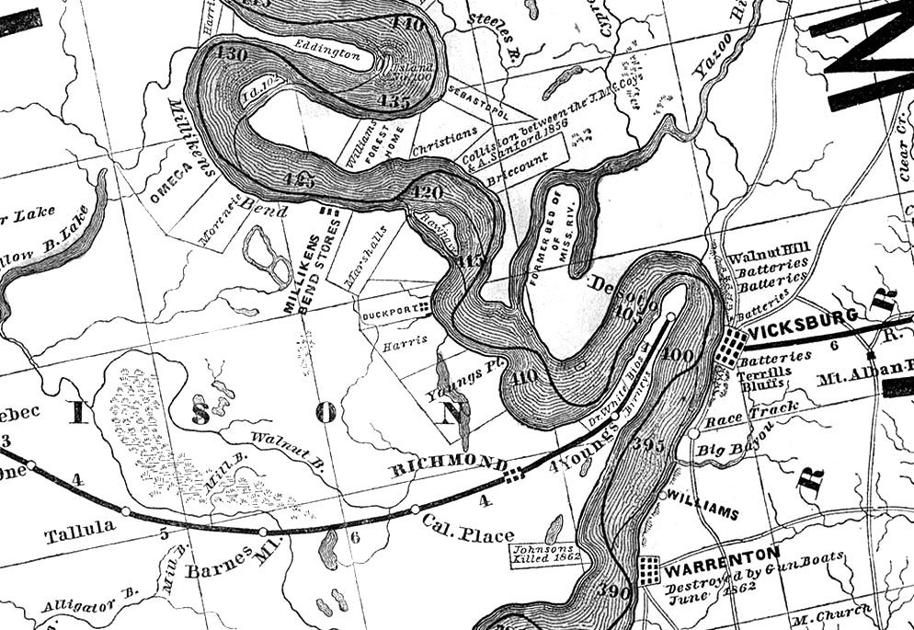

The battle took place during the last month of U.S. Grant's seven month effort to capture the citadel of Vicksburg, the last crucial strategic outpost held by the Confederacy on the Mississippi River. Milliken's Bend lies about 15 miles north of Vicksburg on the opposite (west) side of the river and is within the northernmost parishes of Louisiana along the great river. The slave population of these parishes amounted to from 80% to more than 90% of the total population and as the Union Army advanced it caused panic among plantation owners and a recruitment opportunity for the Federals in light of policy changes that allowed for the enlistment of what were called the United States Colored Troops.

Barnickel gives a good accounting of the battle itself, which was little known to most Civil War buffs like Barnickel (and myself) until in 1992 she stumbled across a reference to a Union officer "murdered" and decided to pursue the story. As an archivist with the Nashville Public Library she knew how to do research but with having a full-time job it took her 20 years to complete the book which was published in 2013 to rave reviews by the Civil War press and historians.

In the context of the great battles of the war, Milliken's Bluff was a small affair with only about 1,500 soldiers involved on each side but casualties were significant. About 12% of the Confederate force was killed or wounded and a third of the Union force (including an understrength white regiment from Iowa) killed, wounded, or captured. One of the black regiments suffered 68% losses, including 23% killed, more dead than the 1st Minnesota in its famed suicidal charge at Gettysburg. Though driven back to the river bank, the Union troops held on and eventually the attacking Confederates withdrew. And it led to more Union officers and soldiers admitting (sometimes grudgingly) that blacks could be effective soldiers.

What I enjoyed most about the book were the parts before and after the battle. We learn about the Confederate attacking force consisting of four regiments from Texas and the background of turmoil in the regions of that state from where they came. We learn about plantation life and the abrupt and confusing changes confronting the former slaves when the Union Army entered the area. We learn about how the plantation owners reacted to the uncertain fortunes of war and their constant fear of a slave uprising.

After the battle Barnickel investigates the confused over Confederate policies towards captured black soldiers and their white offices along with the rumors of Rebel execution of captured white officers from the black regiments, rumors proved true in at least two instances, and which contributed to the decision of the Lincoln Administration to suspend prisoner exchanges with the South. And she recounts how the battle was mostly not remembered for a century (aided by the immersion of the battlefield under the shifting waters of the Mississippi and the lack of acknowledgement of the role of black soldiers in the war), something that has changed in recent decades.

Most of all, I appreciated the lack of presentism and lecturing in the book. The author presented her findings and goes to great effort to try to understand everyone as they existed and thought in the 1860s, not in the 21st century. She lets the reader draw their own conclusions.

No comments:

Post a Comment