The finest pop song about an historical event is undoubtedly Roads To Moscow, the 1973 song composed and recorded by Al Stewart which I saw performed in 1974 at the Orpheum Theater in Boston while he was on tour in support of the album Past, Present, and Future. The events he describes began more than 78 years ago as Operation Barbarossa, the German surprise attack on the Soviet Union, triggering the bloodiest conflict in human history. By its end in May 1945, 4.3 million Germans were dead, mostly military personnel, and perhaps up to 27 million Russians, two thirds of them civilians.

Stewart's song balances a vivid, poignant, and historically accurate lyric with a lovely melody, a Russian influenced chorus, and an evocative and emotional arrangement. He tells the story of a Soviet soldier, one of tens of millions of people caught in the horrific tragedy caused by two of the most brutal regimes to ever be inflicted upon the human race - Nazi Germany, led by Adolph Hitler, and the Communist Soviet Union of Josef Stalin. It's a world of spiritual darkness and limited and terrible choices for the common people trapped by those events, a dilemma also brought to life by Alan Furst in his splendid series of novels set in the same time period - particularly Night Soldier and Dark Star.

Let's look at the lyrics and explore the song in more detail.

They cross over the border the hour before dawnAt about 315am on the morning of June 22, 1941, the German army launched Operation Barbarossa. The attack, including 14 Finnish and 13 Romanian divisions, involved 3.8 million soldiers, 3,400 tanks, 3,500 aircraft and 700,000 horses. Facing the onslaught were about 2.5 million frontline Soviet troops (the Red Army had about 4 million men under arms in total in the European part of the country).

Though Hitler and Stalin had been allies since the August 1939 signing of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Treaty, which divided Poland and the Baltic States between them, they were long-term ideological enemies and a conflict was inevitable at some point. However, the specific timing of the German attack was dictated by Hitler's desire to remove what he viewed as Britain's last hope for support in the war, the same motive that drove Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 (for more on this read Bonapartaroo Barbarossa).

Ideological considerations drove Nazi decisions as to how the war would be conducted. The inhabitants of occupied portions of the Soviet Union were to be starved, driven out, or left as slave labor for German settlers, captured Red Army communist commissars to be executed, and roving extermination squads (Einsatzgruppen) organized that would ultimately kill a million Jews.

In the months leading to the attacks, Stalin dismissed multiple warnings from his own intelligence services as well as from Churchill and Roosevelt, claiming they were provocations designed to entice him into a war with Germany that would only benefit the Western capitalist powers. As late as the night of June 21-22 he ordered the execution of German defectors who entered Soviet lines to warn of the imminent attack. The result was that Red Army troops were left deployed in forward positions near the border, in vulnerable formations ill-suited to defense.

The Soviet Army was still recovering from Stalin's 1937-38 purge (possibly triggered by information planted by German agents) of senior military leadership in which at least 75% of these officers were killed, and its poor performance in the 1939-40 Winter War with Finland, gave the German military what proved to be unwarranted confidence that the Russians would be quickly defeated. This overconfidence also contributed to the inexplicable lack of attention by the Germans to the logistical challenges of a massive campaign designed to penetrate deeply into the Soviet Union, challenges that were ultimately to doom Barbarossa.

The border referred to in the lyric was different from the 1939 Soviet border. With the 1939 pact, Stalin was able to occupy half of Poland, all of the Baltic States and the Romanian province of Bessarabia. By advancing the border, he gained strategic depth against attack, while also arresting, murdering, and deporting hundreds of thousands of citizens of those countries who he believed might oppose his plans (a sordid tale told in disturbing detail in Timothy Snyder's Bloodlands). In addition, with his surprise attack on Finland in October 1939 he gained buffer room for Leningrad and the crucial northern port of Murmansk.

Moving in lines through the dayThe Luftwaffe destroyed over 2,000 Soviet aircraft on the ground that first day, losing only 35 planes in its attacks. More than 3,900 Soviet planes were destroyed in the first three days, giving the Germans overwhelming air superiority.

Most of our planes were destroyed on the ground where they lay

Waiting for orders he held in the woodIn those first days and weeks many Soviet troops found themselves isolated behind the rapidly advancing Germans and without order amidst the command chaos. "The Front" refers not to the front lines where the soldiers were, but to the organization of Russian armies into "Fronts", equivalent to American Army Groups on the Western Front. In other words, they heard nothing from the High Command.

Word from the Front never came

By evening the sound of the gunfire was miles away

Ah, softly we move through the shadows, slip away through the trees

Crossing their lines in the mists in the fields on our hands and our knees

And all that I ever, was able to see

The fire in the air glowing red, silhouetting the smoke on the breeze

While many isolated or surrounded soldiers surrendered (nearly 3 million by the end of 1941, 3/4 of whom would die in German captivity) many thousands were eventually able to find their way back through gaps between the rapidly advancing German Panzer units and the slower infantry following behind to rejoin their comrades, our narrator being one of those. Others remained uncaptured but behind enemy lines, becoming the core of the partisan units that would harass the Germans for years (and who make an appearance later in the lyrics).

All summer they drove us back through the UkraineIn this passage, the narrator uses the terms "us" and "we" in reference not to his personal location but rather to the overall plight of the Red Army.

Smolensk and Vyazma soon fell

By autumn we stood with our backs to the town of Orel

The German attack was divided into three army groups. Army Group North advanced through the Baltic States towards Leningrad, while Army Group South drove the Soviets, "back through the Ukraine", culminating in September with a great encirclement near Kiev in which more than 700,000 Soviets were killed or captured.

The third, and initially most powerful, group was Army Group Center, taking the road to Moscow along with Smolensk, Vyazma, and Orel were located. The Battle of Smolensk lasted from July 10 to September 10, with the Red Army losing nearly a half million soldiers dead, wounded, or captured. The battle was prolonged because in its early stages Hitler diverted panzer units to the south for the Kiev encirclement. The delay in capturing Smolensk may have fatally delayed the German drive on Moscow.

With the panzers returning to Army Group Center, the advance on Moscow resumed in late September, racing against the onset of winter. During October, the Germans pulled off two more giant encirclements at Vyazma and Bryanks, in which another million Soviet soldiers were killed or captured. Orel fell on October 3 to General Guderian's tanks.

Closer and closer to Moscow they comeOn November 15, the Germans began their final push on Moscow. General Heinz Guderian (1888-1954), commander of the Second Panzer Army, is considered one of the finest tank generals of the war, performing brilliantly during the Poland invasion and then leading the armored spearheads in the 1940 French campaign. Guderian's task was to approach the Soviet capital from the southwest and encircle it. Though he made some advances, his overextended forces were halted short of the capital and left in vulnerable defensive positions. On December 26, 1941 he would be dismissed from command because of a dispute with his superiors (including Hitler) over how to respond tactically to the recently launched Soviet offensive. Recalled to duty by Hitler in 1943 after the disaster at Stalingrad, he was charged with rebuilding the army's panzer capabilities. On July 21, 1944, the day after the failed assassination attempt against Hitler, Guderian was appointed Army Chief of Staff. Though often arguing with Hitler about tactical decisions, he remained a faithful supporter of the Fuehrer until the end of the war.

Riding the wind like a bell

General Guderian stands at the crest of a hill

(Guderian)

Winter brought with her the rainsIn this section, two weather periods are mixed together. From late October until mid-November came a period of cold rain, turning the primitive Soviet road network into a sea of mud. Then came freezing temperatures, making the roads stable and more passable. The final German push was launched in this window before the onset of brutal cold and snow made offensive operations much more difficult.

Oceans of mud filled the roads

Glueing the tracks of their tanks to the ground

While the sky filled with snow

(Mud season, November 1941)

And all that I ever was able to seeNow the red is silhouetting "the snow on the breeze" rather than "the smoke on the breeze" of the first verse, signaling the passage of time from the warmth, sun, and disaster of June to the bitter cold, snow, and hope of December.

The fire in the air glowing red silhouetting the snow on the breeze

In the footsteps of Napoleon the shadow figures stagger through the winterThe German offensive continued until December 5 under increasingly taxing conditions with heavy snow and temperatures plunging to well below zero. Counting on achieving complete victory by the end of fall, German soldiers had not been issued winter clothing, nor were tanks, assault guns, and motor vehicles designed and equipped to operate in these conditions. At these temperatures the recoil fluid, lubricating oil and firing pins on German artillery, anti-tank, and machine guns failed, tank turrets would not turn and trucks had to be kept constantly running, using precious fuel. And all these troubles amplified by the already overstressed German supply system virtually collapsing in the winter conditions.

Yet despite these difficulties, isolated German units got within 15 miles of the Kremlin, while to the northwest the main German forces were within 25 miles of the city.

A German officer wrote of conditions during the advance:

It is icy cold . . . To start the engines, they must be warmed by lighting fires under the oil pan. The fuel is partially frozen, the motor oil is thick, and we lack antifreeze to prevent the cold water from freezing.On December 3, the commander of Fourth Panzer Group reported its offensive combat power "has run out" because of "physical and moral over-exertion, loss of a large number of commanders, inadequate winter equipment".

The remaining limited combat strength of the troops diminish further due to the continuous exposure to the cold. It is much too inconvenient to shelter the troops from the weather . . . In addition, the automatic weapons of the groups and platoons often fail to operate, because the breeches can no longer move.

Finally recognizing the reality of the brutal conditions and the disintegration of offensive capabilities Hitler and the High Command issued a halt order on December 5.

References to Napoleon were also a constant theme of Soviet propaganda which constantly reminded German troops of the fate of the last western invader, whose myth of invincibility, along with his army, disappeared in the Russian winter.

Falling back before the gates of MoscowWhat kept the German high command pressing ahead for so long despite the casualties and exhaustion of men and equipment was the persistent belief the Russians had exhausted their reserves and were on the verge of collapse. It was a massive miscalculation and demonstrated the complete failure of German intelligence assessments. They underestimated the willingness of Stalin to move troops from the Soviet Far East as well as the capability of the brutal and ruthless Soviet system to mobilize an almost endless number of reserves (unlike Hitler, who resisted fully mobilizing the German economy and populace until 1944, Stalin immediately took such measures). Between June 22 and December 31, the Soviets lost 4 million men, the equivalent of its entire army on June 22 yet still had 4 million under arms at the end of the year. It is hard to believe any other society surviving with that magnitude of loss in such a short time.

Standing in the wings like an avenger

Less than 24 hours after the German offensive halted, the Soviets began launching their own attacks, designed to push back and isolate the German forces near Moscow. In a series of actions lasting until the beginning of March 1942, the exhausted Germans were forced back more than 100 miles, permanently eliminating the threat to Moscow.

While Soviet soldiers were somewhat better equipped for the weather, the winter conditions still took a toll, a toll only enhanced by Soviet commanders still favoring frontal assaults. Thus, despite its success, the tactical shortcomings of the Red Army can be seen in the disparity in casualties during its three month offensive - 1.6 million for the Soviets versus 262,000 for the Germans.

And far away behind their lines the partisans are stirring in the forestThough not a major factor in 1941, by the following year the partisan threat became a major problem for the extended supply lines of the German army. Partisan warfare in Russia was on a completely different, and larger, scale than in most of the rest of Europe, involving huge numbers, semi-organized and large scale assaults on German rear lines. Big chunks of the Soviet countryside behind enemy lines remained out of German control throughout the war and forcing many troops to be diverted to fighting partisans.

Coming unexpectedly upon their outposts, growing like a promise

You'll never know, you'll never know

Which way to turn, which way to look, you'll never see us

As we're stealing through the blackness of the night

You'll never know, you'll never hear us

And the evening sings in a voice of amber, the dawn is surely comingUsing "amber" in this context is very interesting. Amber is a fossilized tree resin, valued as a gemstone. From 1500 BC there was an Amber Road by which this material was moved in trade from the shores of the Baltic to the Mediterranean. The leading source of amber was near what used to be the city of Konigsberg in Prussia, now known as Kaliningrad and part of Russia since 1945.

The famous Amber Room was initially constructed in Konigsberg and gifted in 1716 by the Prussian King to Peter the Great of Russia. Installed in a palace outside of Petersburg (later Leningrad), the room was expanded, eventually covering 590 square feet and containing over 6,000 pounds of amber on panels backed with gold leaf and mirrors.

(The Amber Room)

During the war the German Army dismantled the Amber Room and transported it back to Konigsberg. Disappearing at the end of the war, its location remains unknown, one of the last mysteries of the war.

The voice of amber is soothing - its message that things will get better. The next lines tell us how:

The morning road leads to StalingradWe've moved ahead several months to the summer of 1942. Unlike 1941, when the German Army was powerful enough to attack the Soviets from across its entire front, the Nazis summer offensive would be more limited in scope.

And the sky is softly humming

On June 28, the Germans attacked in the south, aiming for the oil fields of the Caucasus region and the heavy industrial town of Stalingrad. The Germans advanced quickly, nearly reaching the Caspian Sea, but became bogged down in Stalingrad, with an increasingly obsessed Hitler insistent upon its capture. The fighting lasted for almost six months ending in catastrophe for the Nazi regime with the destruction of the Sixth Army and the allied Hungarian and Romanian armies, along with heavy losses in other German units. Of 91,000 prisoners taken by the Russians only 5,000 ever returned to Germany, some not until a decade after the end of the war. The cost of victory was staggering for the Red Army - another 1.1 million dead, wounded or captured.

On June 28, the Germans attacked in the south, aiming for the oil fields of the Caucasus region and the heavy industrial town of Stalingrad. The Germans advanced quickly, nearly reaching the Caspian Sea, but became bogged down in Stalingrad, with an increasingly obsessed Hitler insistent upon its capture. The fighting lasted for almost six months ending in catastrophe for the Nazi regime with the destruction of the Sixth Army and the allied Hungarian and Romanian armies, along with heavy losses in other German units. Of 91,000 prisoners taken by the Russians only 5,000 ever returned to Germany, some not until a decade after the end of the war. The cost of victory was staggering for the Red Army - another 1.1 million dead, wounded or captured.(Russian soldiers, Stalingrad)

In a military sense the failure to knock the Soviets out by the fall of 1941 was the turning point in the war, the point where unconditional victory by Germany became impossible but Stalingrad was the symbolic turning point of the war and both Stalin and Hitler were aware of its symbolism at the time. The horror of the battle from the Russian perspective is captured best in Life and Fate by Vassily Grossman, one of the greatest works of 20th century literature, in a section recounting the struggle of one Red Army squad to hold a ruined building amidst the rubble of the city. Of course, being a Russian novel, everyone dies.

After Stalingrad, German military leaders no longer believed the war could be won, though it was not certain how long it might take the Soviets to win.

Two broken Tigers on fire in the nightThe lyrics here are very cleverly structured. The first line tells us of "two broken Tigers" followed by a reference to "the final approach" but we don't know where or when it is. The next line tells us it's been "almost four years that I've carried a gun", placing us in 1945, but still not giving us a location as Soviet armies are fighting from the Baltic to Hungary. Then it's revealed that the flaming Tigers are also "lighting the road to Berlin", creating a vivid and precise word picture.

Flicker their souls to the wind

We wait in the lines, for the final approach to begin

It's been almost four years, that I've carried a gun

At home it'll almost be spring

The flames of the Tigers are lighting the road to Berlin

The Tiger was the heaviest and most powerful tank produced by Germany during the war. Like much German equipment it was over engineered, overly complex to manufacture and required high level maintenance to keep operational. The Tiger I was produced from 1942 to 1944 and the Tiger II from 1944 on, but fewer than 2,000 made it to the army. When it was available and running the Tiger proved devastatingly effective.

(Tiger II)

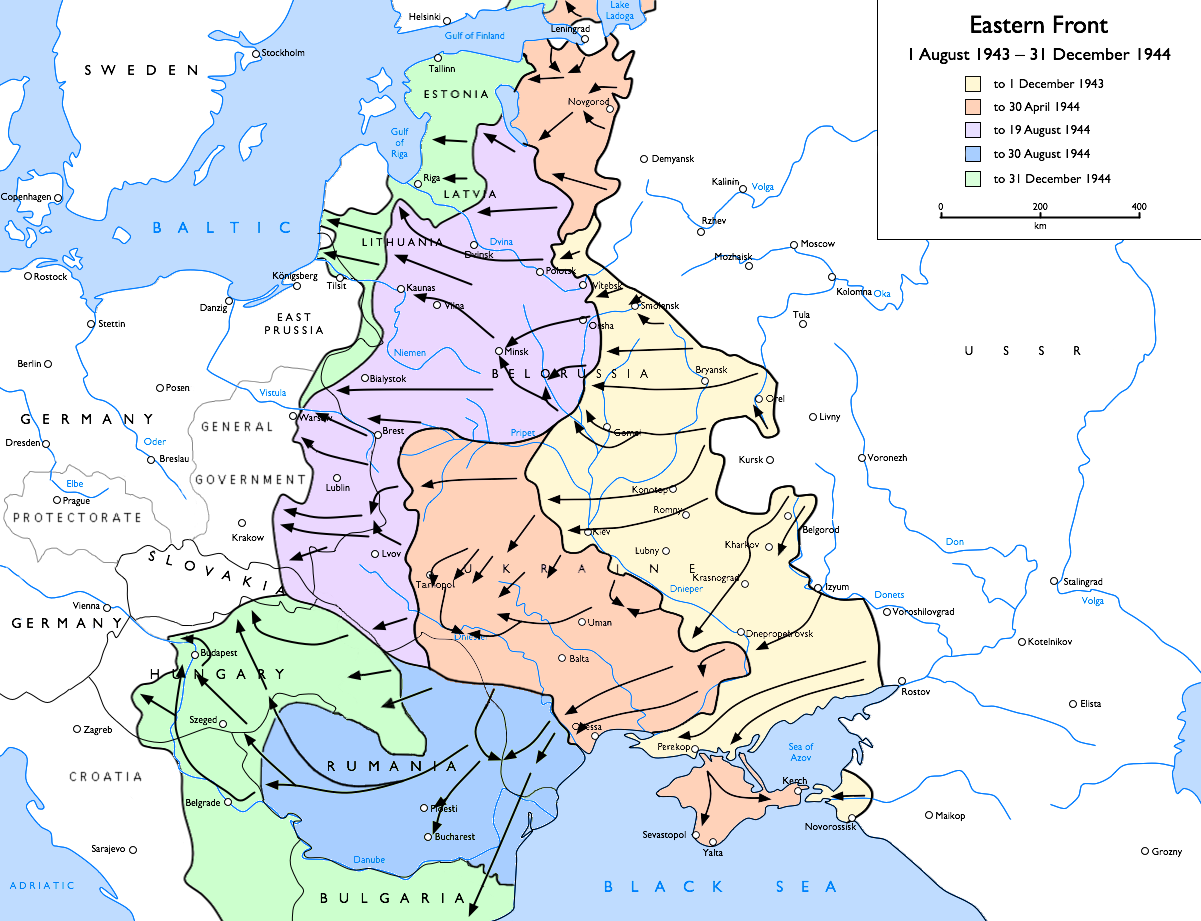

It's now April 16, 1945. The Red Army is less than 50 miles from Berlin. Much has transpired since the German surrender at Stalingrad in February 1943. In July 1943 Hitler attempted his last major attack on the Eastern Front near the city of Kursk. It quickly proved unsuccessful, the Soviets counterattacked, and from then until the end of the war the Red Army conducted a series of attacks. The German siege of Leningrad ended and most of the Ukraine was reconquered by the end of 1943. In June 1944, the Soviets crushed Army Group Center and drove the Germans out of Russia, advancing into Poland where by late July they were on the outskirts of Warsaw. Then followed another of the countless tragedies of the war when the Polish Home Army rose up to evict the Germans. Stalin, who opposed the anti-communist Poles, ordered the Red Army to stand by while the Nazis crushed the uprising, killing 200,000 Poles and razing the city (for more on the uprising read Warsaw Does Not Cry).

In late 1944, the Soviets advanced into the Balkans, causing Romania and Bulgaria to switch sides and reaching the borders of Hungary.

On January 12, 1945 the Russians renewed their attack on the Polish front, sweeping away the Germans quickly advancing to the Oder River near Berlin, where they paused to regroup for the final assault.

Ah, quickly we move through the ruins that bow to the groundThe Berlin campaign lasted from April 16 through May 2. Though the assault contributed to the "ruins that bow to the ground" much of the city was already ruined by American and British bombing raids, some consisting of more than 1,000 bombers striking the city.

The old men and children they send out to face us, they can't slow us down

All all that I ever, was able to see

The eyes of the city are opening now, it's the end of a dream

The reference to "old men and children" refers to the Volksstrum ("People's Storm"), a national militia consisting of all men between 16 and 60 capable of bearing arms, formed in October 1944, as the manpower needs of the crumbling Third Reich became ever more desperate (though even boys of 14 and 15 would see service by the end). Poorly armed and trained, the Volkssturm units were of varying effectiveness and took heavy casualties.

Notice the contrast with the opening verse of the song. In 1941, the narrator speaks of defeat, confusion, and retreat; four years later he is moving triumphantly forwards to victory.

(Berlin 1945)

Despite the claim that "old men and children . . . they can't slow us down", the Volkssturm and remaining regular Wehrmacht units imposed heavy losses on the Army army - 79,000 dead and 270,000 wounded in less than three weeks, a per day toll higher than any the Soviets had suffered since the dark days of 1941. The human cost was made higher by Stalin's cynical move to place Marshals Zhukov and Koniev in competition to be first to Berlin, relentlessly mocking and scolding them, leading to reckless frontal assaults, particularly by Zhukov (for more on him read The Secret of Khalkin Gol). And, with the encouragement of Stalin and the Red Army command, the victorious soldiers took a terrible vengeance on German civilians.

I'm coming home, I'm coming homeThe lyric brims over with optimism. Against all odds, our narrator has survived and looks forward to being reunited with his family. In reality the odds were low that any soldier on the front line on June 22, 1941 would be alive and healthy enough to fight continuously and still be in the Berlin fighting.

Now you can taste in the wind, the war is over

And I listen to the clicking of the train wheels as we roll across the border

8.6 million Red Army personnel died in the war; effectively the original 1941 army was killed twice over. In comparison, the United States suffered 296,000 battlefield deaths with another 100,000 dead due to accidents and illnesses.

Nor were all the Russian dead solely the responsibility of the German army. Life for Red Army soldier during the war was brutal. Commanders employed tactics that wasted countless lives. If you died, particularly early in the war, it was unlikely your family would be notified. Any infraction, real or imagined, was subject to harsh discipline and extreme punishment. During the first 18 months of the war (the only period for which we have figures), 160,000 Soviet soldiers were executed for cowardice or desertion. By comparison, only one American was executed for these offenses during the entire war. For those not summarily executed there were the Punishment Battalions and Companies to which officers and soldiers were sentenced to be used, in Stalin's words, at "the most difficult parts of the front, to give them the possibility to redeem their crimes against their country with blood". The Punishment units were deployed for tasks such as suicidal front assaults and the clearing of minefields by marching through them, making it no surprise that an estimated 400,000 died in the process. Their existence was such an embarrassment to the Soviets after the war that the existence of the units was officially denied.

And there were the Red Army's blocking detachments formed to shoot down retreating soldiers - retreating Red Army soldiers. In this clip from the movie Enemy At The Gates, which takes place at Stalingrad, you can watch (about 2 minutes in) a blocking detachment in action (the first 20 minutes of the movie are stunning and accurate, after that it falls apart).

The optimism of those that survived extended beyond the relief of being alive and reuniting with family. The memoirs and recollections of returning soldiers and officers are filled with belief and hope that conditions in the Soviet Union would be improved. There was a feeling that, through their war effort, the common Soviet citizen had proven to Stalin they could be trusted, that the regime need not fear them, that the fear of being subject to arbitrary justice would end and there would be a new start for the Soviet people and a new and more cordial relationship with their government.. It was not to be.

And now they ask me of the timeIn his account of the German-Soviet struggle, Absolute War, author Chris Bellamy writes, "the Red Army was the only one in the world where being taken prisoner counted as desertion and treason". Stalin believed any soldier who allowed himself to be captured was a traitor and potential counter-revolutionary, and that Russians exposed to Westerners for any length of time became a danger to the Soviet state. Bellamy adds:

That I was caught behind their lines and taken prisoner

"They only held me for a day, a lucky break", I say

They turn and listen closer

I'll never know, I'll never know

Why I was taken from the line and all the others

To board a special train and journey deep into the heart of Holy Russia

And it's cold and damp in this transit camp

And the air is still and sullen

And the pale sun of October whispers

The snow will soon be coming

The Soviet government and military command had absolutely no interest in what happened to Soviet people in German captivity. When prisoners of war who survived were released at the end of the war [3 of the 4 million POWs died due to the German policy of exposing them to the elements and leaving them to starve, though a small number also died serving as guinea pigs during the initial testing of the gas chambers used at Auschwitz], they were usually sent to the Gulag or shot, and the same fate even befell many who had fought and crawled their way out of German encirclements during the war.Our narrators falls into this last group. His years of valiant service and suffering are to no avail.

Also subject to this treatment were civilians who either volunteered or been seized and taken to Germany as slave laborers. Bellamy estimates that up to 1.8 million returning Soviet citizens were sent to Gulag camps or shot.

In Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege, Anthony Beever tells the tale of a Soviet lieutenant caught in this madness. Captured by the Germans in August 1942, he manages to escape and rejoin the Red Army, where he is promptly arrested, charged as a deserter, and sentenced to a Punishment Company. Realizing his sentence is an effective death penalty, he deserts to the Germans! We don't know his fate but it is unlikely he had a happy ending.

To their mutual disgrace, both Britain and America contributed to this horror. Between 1945 and 1946, the two countries forcibly repatriated over a million Russians who did not want to return to the Soviet Union. While it was the British who insisted on honoring agreements made with Stalin during the course of the war, the United States eventually went along. The returnees were among those sent to the Gulag or shot.

Even for those escaping the Gulag or execution, optimism proved misplaced. Stalin believed that after the "laxity" of the war years, Soviet discipline needed to reimposed to prevent any sliding back from the pre-war accomplishments of the state. The post-war years proved grimly repressive with further waves of purges and the elimination of those tiny, fragile zones of personal autonomy some had carved out during the war. Stalin even ordered the removal of crippled and disabled war veterans from the streets of Moscow because he felt their presence demoralizing. It was in this atmosphere that a young returning officer, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, found himself sentenced to ten years in the Gulag for telling a joke about Stalin.

And I wonder when I'll be home again and the morning answers, "Never"I find these the saddest line in music and no matter how often I hear them they affect me as powerfully as the first time. They represent the betrayal of the hopes and dreams of people caught up in a horrible time, who thought they'd survived the worst, only to find themselves condemned to death, exile, continued fear and hopelessness.

And the evening sighs and the steely Russian skies go on forever

We take leave of our narrator as he disappears into the mist beneath the steely Russian skies passing to an unknown fate, like so many other millions. We'll end with some lines from the poet Osip Mandlestam (1891-1938), who himself died in a Gulag transit camp after sentencing for committing "counter-revolutionary activities" consisting of writing a poem mocking Stalin.

Mounds of human heads(Gulag prisoners)

Are wandering into the distance

I dwindle among them

Nobody sees me

(Prisoner 282, Solzhenitsyn)

No comments:

Post a Comment