Captain Major of the Seas of Arabia discussed how Portugal became the dominant power in the Indian Ocean during the 16th century. The Ottoman Age of Exploration by Giancarlo Casale provides a different perspective on that time and place.

The Ottomans have been frequently portrayed as reactive and relatively uninterested in the Indian Ocean but Casale's thesis is that the Ottoman encounter with the Indian Ocean and that empire's attempts to exert its controls had parallels to the Western European experience during the age of exploration in the Americas and the Indian Ocean. (For more THC posts on the Ottomans go here.)

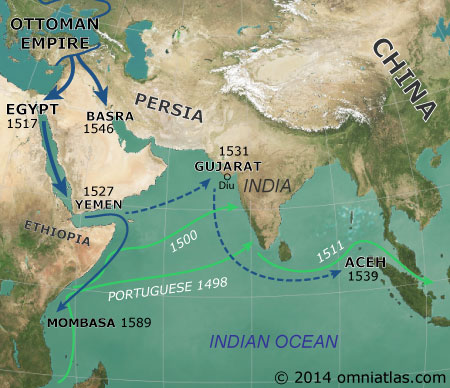

It was in 1517 that the Ottomans first came into direct contact, via the Red Sea, with the Indian Ocean and its surrounding territories after destroying the Mamluks and occupying Egypt. Before carrying forward the story, Casale gives us some context. He reminds us of the relative isolation of Western Europe, during the 15th century, before Columbus sailed, at a time when Muslim merchants could travel "virtually unobstructed" from Morocco to Southeast Asia, and Ming China was sending naval expeditions which reached Ceylon, the Persian Gulf, and East Africa. But Muslim is not equivalent to Ottoman. In the 15th century, the Ottomans were focused on expansion in Europe from their original base in what is now western Turkey. They conquered Greece, the southern Balkans, and made Constantinople their capital after its capture in 1453. Ottoman merchants were not traversing the Muslim world at the time.

As to the Portuguese, who reached India in 1498, pioneering a direct trade route for precious spices from South Asia to Europe via the Cape of Good Hope, they continued to have bigger goals. In the short term the Portuguese royal family used the wealth generated in the spice trade to finance its plans for expansion in Morocco, but its longer term goal was even more ambitious. Casale writes:

"As contemporary records make clear, they were well aware of the superiority of the traditional Egyptian route, such that Egypt and the Holy Lands remained at the very center of their strategic calculations throughout the early decades of the sixteenth century. By their own admission, in fact, early Portuguese strategists hoped not to permanently bypass Egypt, by means of their blockade of the Red Sea, by rather to pave the way for an invasion of Egypt by weakening the Mamluks' access to customs revenues and raising money for themselves in the process".

Ultimately the goal was to conquer Egypt and the Holy Land and open a more direct, less risky, and less expansive route to the Indian Ocean. In retrospect it seems a lunatic aspiration, given Portugal's limited financial and manpower resources, but what that country and Spain accomplished in the early 16th century in the Americas, Africa, and South Asia on a relative shoestring budget showed anything was possible.

Prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean, the spice trade to the Middle East, North Africa and Europe was routed through Egypt. Between its agricultural productivity and the revenues generated via the spice trade, Egypt prospered (for the similar role Egypt played in the Roman Empire, read The Farthest Outpost). With its conquest, the Ottomans now had access to that trade, but faced Portugal's efforts to blockade the Red Sea and seize outposts in the Persian Gulf and along the southern coast of Arabia.

Rapidly acquiring knowledge of South and East Asia and with access to maps and charts of the area, in the 1520s the Ottomans began to challenge Portugal's dominance, first attempting to conquer Yemen at the south end of the Red Sea, and developing alliances with the rulers of Gujarat, in what is now western India, efforts that were to continue until near the close of the century.

Casale documents the difficulties faced by the Ottomans, attributable to several factors:

The lack of a direct sea link between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, meant an entirely new fleet had to be constructed for operations in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, a costly proposition as galley and ship construction was extremely expensive. On three occasions during the century, the Ottomans began construction on a canal to link the Nile with the Red Sea, but abandoned each due to cost and technical issues.

Difficult logistics. The lack of sufficient mature forests in Egypt and Arabia meant wood and other basic raw materials needed for shipbuilding had to be imported from Anatolia or Lebanon, and expensive and time consuming proposition.

Continued instability in Yemen. After its initial conquest in the early 1520s, there were several revolts by Yemenite tribesmen, a couple of which temporarily ended Ottoman control of the territory. These revolts impeded Ottoman plans for action in the Indian Ocean and, once again, required diversion of financial, naval and land forces to reassert control.

Over and above these regional issues there was an ongoing back and forth in Constantinople involving the Sultans and their viziers over where the Empire's priorities should be - Europe? The Safavid dynasty in Iran? The Indian Ocean? The degree of Ottoman aggressiveness in South Asia depended on how the winds were blowing in the Bosporus, and the winds frequently changed.

Despite these challenges the Ottomans accomplished quite a bit during the 16th century. In the 1530s the dynasty conquered Iraq, seizing Basra, giving it access to the Persian Gulf trade and opening a new front with Portugal, which had taken Hormuz, at the narrowest part of the Gulf, in 1509.

The Ottomans were able to prevent Portugal from gaining a permanent foothold in Yemen, despite repeated efforts, and finally decisively defeated efforts to blockade the Red Sea.

Along with maintaining, at a high cost, its position in Yemen, the Ottomans also seized Eritrea on the opposite side of the Red Sea.

Developed close relations with Gujurat and Aceh, at the north end of the island of Sumatra, supplying arms and troops to both to support their opposition to the Portuguese.

In 1589, a raid by corsair Mir Ali, came within a whisker of evicting Portugal from the Swahili Coast of East Africa, which would have transformed the entire conflict and the ability of the Iberian Kingdom to continue its spice trade. Only a series of freakish events prevented this from becoming a reality.

All of this helped the Ottomans to develop a free trade position for its merchants which allowed it to become a bigger player than Portugal in the spice trade.

Perhaps the biggest threat was the plan for a major Ottoman offensive in 1567, which was derailed by yet another revolt in Yemen. This involved a coordinated offensive with the Ottomans sending a large fleet into the Indian Ocean, also involving Muslim Indian states and the Sultanate of Aceh (which would move against the Portuguese stronghold of Malacca).

Despite its ultimate failure, Portugal remained continually worried about the Ottoman threat, but by the end of the century both powers were in decline.

The royal obsession with Morocco led Portugal to disaster in 1578, when its young king launched a crusade to conquer that North African kingdom, an effort that resulted in its army being destroyed and the king and much of the royal male line killed. Two years later, Portugal was absorbed by King Philip of Spain, for whom the Indian Ocean was a backwater to which he would pay little attention. By the time Portugal became independent again in 1640 most of its possessions were gone, taken by the English and Dutch.

The Ottomans began a period of stagnation in latter decades of the century, with less resources being allocated to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. In 1622, the Iranian Safavids took Hormuz from Portugal, severing Ottoman Basra's links with India and by the 1630s, Ottoman rule of Yemen permanently ended, weakening the Red Sea-India connection.

Along with telling this story, Casale's book also introduces us to fascinating characters like Sokollu Mehmed, the long serving vizier from 1565 to 1579, and advocate for an expansive Indian Ocean policy, Ozdemir Pasha, who rose from lowly origins to suppress a huge revolt in Yemen and conquer Eritrea, and Sefer Reis, the corsair, whose clever tactics drove the Portuguese from the shores of Arabia and the Red Sea.

No comments:

Post a Comment