(NOTE: This was prematurely published but I'll leave it here from now and revise and extend it as I originally planned when I can get to it).

I recently read The Earth Is Weeping; The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West by Peter Cozzens, an account of the years from the Civil War to the final surrender of the Lakota Sioux in January 1891 after the fight at Wounded Knee. Over the past few years, I've also read The Apache Wars by Paul Hutton, The Heart of Everything That Is by Paul Drury and Tom Clavin (the story of Red Cloud, the only western Indian to defeat the US Army and obtain a favorable treaty), and Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches by SC Gwynne, all of which are worth reading.

Each book is a sad tale of conflict, misunderstanding, betrayal, and broken promises. Beyond that it made me think about what were the realistic alternatives to what happened and the legacy that continues to this day as described by Naomi Schaefer Riley in her recent book, The New Trail of Tears: How Washington is Destroying American Indians.

Before returning to the Indians of the American West let's go all the way back to the initial European settlement of the Americas. The chances of the Indians of the Western Hemisphere meeting Europeans on grounds of equal strength were fatally compromised at the beginning, when they were exposed to illnesses for which they had no immunity. This unintended biological invasion diminished native populations between 70% and 90% across both continents within several decades of the first voyage of Columbus (for its impact on Mexico see Ten Years After: 1519-1529). In 1620 when the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth they found deserted Indian villages along the coast, with most of the population gone after an epidemic fueled by contact with Portugese and English fishermen who had trawled the area over the previous two decades.

Various Indian attempts to repel the invaders in the 16th and 17th centuries failed, often because of disunity and rivalries among the tribes (see Bloody Brook and The Sudbury Fight). One revolt was temporarily successful when the Pueblos drove Spanish settlers from New Mexico only to have their efforts reversed twelve years later (see Pueblo Revolt).

However, while Europeans cleverly manipulated tribal rivalries (Cortez' conquest of Mexico would have been impossible without the aid of tribes opposed to Aztec rule), Indians were capable of the same behavior. In North America this meant exploiting the rivalry of French and Britain, allowing Canada west of Quebec and American west of the Appalachians to avoid European settlement for a century. This strategy became doomed when France ceded its North American posessions to Britain when the French & Indian War ended in 1763. While the tribes tried a variant of this strategy during the American Revolution, continuing until the end of the War of 1812 during which time many allied themselves with the British, it proved unsuccessful as the English eventually withdrew from contesting the ambitions of the new American nation.

Showing posts with label American West. Show all posts

Showing posts with label American West. Show all posts

Thursday, March 23, 2017

Friday, October 7, 2016

Kit Carson Meets General Kearny

October 6, 1846. It was early autumn and cooler weather had finally arrived as three hundred cavalry troopers rode south for eleven days along the Rio Grande, crossing fields and stands of cottonwoods with the arid mountains looming above them, farther away from the river's banks. They were camped near the deserted town of Valverde, abandoned by its frightened inhabitants because of constant Navajo and Apache raids. During the morning, clouds of dust began rising to the west, the direction to which they'd eventually be turning. Making out about a dozen mounted men riding towards them, they went on alert, thinking they might be Indians, only relaxing once they realized Americans were among the riders.

As the riders entered the camp, a small (5'5''), thin (less than 140 lbs), sunburnt man with lanky blond hair down to his shoulders, dismounted, informing the troopers he was carrying important messages from California to be delivered to Washington DC. When asked his name, the man replied, "I''m Kit Carson".

(Kit Carson)

(Kit Carson)

It was General Stephen Kearny's introduction to the scout who had already gained a national reputation.

We've told part of the story of how they came to meet in Forgotten Americans: Henry Lafayette Dodge. At the start of the Mexican-American war, Kearny led an army across the Great Plains, capturing Santa Fe in August 1846, after Mexican government officials fled without a fight. Once the territory was secured, Kearny had orders to proceed to California to capture that Mexican state for America. Selecting three hundred of his best cavalry, Kearny left Santa Fe on September 25 (one of his guides being Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the son of Sacagewea, born during the Lewis & Clark expedition). He knew it would be an arduous journey; first south along the Rio Grande, then west across the little known high plains, mountains and Sonoran Desert for 800 miles to San Diego and then fighting the Mexican army.

A New Jersey native, born in 1794, Stephen Kearny enlisted in the army at the start of the War of 1812. Staying in the service after the war, by 1833 he was a Lieutenant Colonel, having, by that time, been a member of expeditions across the Great Plains and into the Rockies. In that year, the well-thought of Kearny became second in command of the newly formed 1st Dragoons Regiment, the regular army's first cavalry unit. Kearny developed the army's initial mounted fighting tactics and is considered the father of the American cavalry. Promoted to brigadier general at the outset of the Mexican-American War, Kearny planned the complex and logistically complicated march of the Army of the West from Ft Leavenworth, Missouri to Santa Fe. He was known as a man of iron will with "a resolute countenance and cold blue eyes which there was no evading".

Carson's journey to Valverde was a little more roundabout. A resident of Taos, New Mexico and married to a Mexican (after two earlier marriages to Arapaho and Cheyenne women), the former mountain man and renowned scout was the best known person in the territory. Born in Missouri in 1809, Kit had moved to Nuevo Mexico, settling in Taos in 1826. Over the next years he trapped, hunted and traded all over the west, from Wyoming and Montana to California. One journey, that would play a role in the events of 1846, was an 1829 trip as a member of a trapping party led by Ewing Young which became one of the first groups to travel cross country from Nuevo Mexico to California.

(Josefa Carson and their son)

(Josefa Carson and their son)

His national renown came about from a chance meeting with John C Fremont on a Missouri River steamboat in the summer of 1842. Fremont, an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was preparing an expedition to map the Oregon Trail as far west as South Pass in Wyoming. Fremont, an ambitious self-promoter, recently married to the daughter of Senate Democratic leader Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri (who, before becoming an ally of President Andrew Jackson, had, in 1813, engaged the future president in a pistol gunfight at a Nashville tavern), immediately hit it off with Carson and asked him to join the expedition as a scout.

Carson would serve as scout on each of Fremont's three journeys of exploration. The first was the successful five month trip to South Pass. The second made both Fremont and Carson famous. They traversed the Oregon Trail to the Columbia River with a side trip to the Great Salt Lake. They then made an illegal trek to California and were saved from suffering from the bad weather in the Sierra Nevada mountains by Carson's wilderness acumen. Expelled from California by the Mexican Governor they returned to the U.S. Fremont's well publicized report on their travels gave Carson copious credit but one event he recounted gained particular notoriety. At one point they came across two Mexicans (a man and boy) in the Mojave Desert who were survivors of a groups ambushed by Indians who had killed the men as well as women (after raping them) and stealing all their horses. Carson and one other man went after the killers, tracking down and killing two of them, recovering the horses and returning them to their owners. Although the first dime novel portraying Carson was not published until 1847 (see below, depicting the incident in the Mojave), it was Fremont's report in 1844 that made Kit famous and earned Fremont the nickname "The Pathfinder".

(from wikimedia)

(from wikimedia)

The third expedition began in the summer of 1845, initially taking Fremont and Kit back to Oregon. They then proceeded into California, still under Mexican rule and possibly in accordance with secret orders from the Polk administration which sought to annex the area. Expelled once again, they returned to Oregon, returning to the state with the onset of war and organizing a revolt of American settlers which soon took control of the state. Fremont, eager to get the news to Washington, asked Kit to carry dispatches across the country, which Carson promised to do in sixty days. Twenty-eight days out he met Kearny.

Carson's news was startling. California was already under American control. Kearny pondered the news and quickly reached a decision. His orders were to proceed to California and he would fulfill them. However, since he was increasingly worried about reports of the unruly Navajo and anticipated no military action on the west coast, he sent most of his three hundred dragoons back to Santa Fe, only retaining one hundred for the next stage of his expedition.

He sent a note to back to Santa Fe notifying them of the change of plan:

Kearny, Carson and the dragoons proceeded south, turning west on October 15, near the modern-day town of Truth Or Consequences. Reaching the headwaters of the Gila River in western New Mexico five days later, they followed it through Arizona (through the present day towns of Safford and Florence, and south of Globe and the Phoenix area, none of which were settled at the time), finally reaching the Colorado River, south of present day Yuma, on November 22. I've visited the pass over which Kearny's men struggled southeast of Globe (photo below).

Four days out of Valverde, Kearny agreed with Carson that his supply wagons were slowing the column down and sent them back to Santa Fe, packing everything on mules, except for two howitzers the general insisted on taking. Even without the wagons it was tough going. One officer wrote of a day on the route in Arizona:

The starving troopers found some succor when they entered the irrigated lands of the friendly Pima Indians, near present day Phoenix and were able to obtain fresh food.

One of Kearny's assignments was to find a viable passage for road and railroad to California and in his official report of December 12, 1846, written after reaching San Diego, he noted:

Crossing the Colorado, Kearny and Carson entered California, but as tough and exhausting as their march had been so far, their difficulties were only beginning, as they situation was much different than what they expected; California was in chaos. Between contention over American military leadership between Fremont and Navy Commodore Stockton, overconfidence and ineptness in their occupation, they enabled the Mexican population to regroup and, with some military reinforcements, to retake much of the state. Kearny could have used those 200 troopers he sent back to Santa Fe.

After climbing 3,000 feet out of the Imperial Valley and into the hills as they approached the California coast, the weary men were confronted by well-trained Mexican lancers on horses. On December 6, Kearny and his men were battered by the lancers, losing 18 dead and seven severely wounded (Kearny being one of them), ending up surrounded on a hilltop. It was Kit Carson to the rescue as he made a daring nighttime escape through the Mexican lines, making his way to San Diego and Commodore Stockton after walking barefoot for thirty hours without food or water. A relief force was sent which rescued Kearny. Kit stayed behind, unable to walk for a week because of the condition of his feet.

On December 12, 1846, General Kearny entered San Diego, completing the 1,900 mile march of the Army of the West, one of the greatest accomplishments in American military history.

Kearny, Stockton and Fremont were able to cooperate in defeating the Mexican forces and reoccupying the entire state but thereafter fell out in a long and dreary dispute which ended up in Kearny sending Fremont back to Washington to be court-martialed, from which he was saved by his political connections.

Kearny served as military governor of California, returning to Washington in 1847 to a hero's welcome and then serving as governor of Veracruz and Mexico City before the signing of the final peace treaty. Unfortunately he contracted yellow fever in Veracruz and returned to St Louis, dying in 1848.

Fremont recovered from his tumultuous adventure in California to become a leading abolitionist and, in 1856, the first Republican Party candidate for President.

Kit Carson went on to have many more adventures. He was a well-respected Indian agent in New Mexico and continued to do tracking. A Union man when the Civil War started, he became commander of 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry and helped to defeat the Confederate invasion of New Mexico in 1862. He also led his troops in the 1864 Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle, fighting Commanche, Kiowa and Apache, one of the largest conflicts between American troops and Indians on the Great Plains.

He also, with misgivings, led the campaign to force the surrender of the Navajo and their transport from their sacred lands to a reservation on the eastern border of New Mexico. Kit then became one of the important voices for allowing them to return to their lands along the New Mexico/Arizona border, which finally occurred in 1868, the same year Carson died.

He always remained a quiet, soft spoken man, embarrassed by his illiteracy. William Tecumseh Sherman met him while in California during 1847:

(Kit Carson, 1868)

(Kit Carson, 1868)

As the riders entered the camp, a small (5'5''), thin (less than 140 lbs), sunburnt man with lanky blond hair down to his shoulders, dismounted, informing the troopers he was carrying important messages from California to be delivered to Washington DC. When asked his name, the man replied, "I''m Kit Carson".

(Kit Carson)

(Kit Carson)It was General Stephen Kearny's introduction to the scout who had already gained a national reputation.

We've told part of the story of how they came to meet in Forgotten Americans: Henry Lafayette Dodge. At the start of the Mexican-American war, Kearny led an army across the Great Plains, capturing Santa Fe in August 1846, after Mexican government officials fled without a fight. Once the territory was secured, Kearny had orders to proceed to California to capture that Mexican state for America. Selecting three hundred of his best cavalry, Kearny left Santa Fe on September 25 (one of his guides being Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the son of Sacagewea, born during the Lewis & Clark expedition). He knew it would be an arduous journey; first south along the Rio Grande, then west across the little known high plains, mountains and Sonoran Desert for 800 miles to San Diego and then fighting the Mexican army.

A New Jersey native, born in 1794, Stephen Kearny enlisted in the army at the start of the War of 1812. Staying in the service after the war, by 1833 he was a Lieutenant Colonel, having, by that time, been a member of expeditions across the Great Plains and into the Rockies. In that year, the well-thought of Kearny became second in command of the newly formed 1st Dragoons Regiment, the regular army's first cavalry unit. Kearny developed the army's initial mounted fighting tactics and is considered the father of the American cavalry. Promoted to brigadier general at the outset of the Mexican-American War, Kearny planned the complex and logistically complicated march of the Army of the West from Ft Leavenworth, Missouri to Santa Fe. He was known as a man of iron will with "a resolute countenance and cold blue eyes which there was no evading".

Carson's journey to Valverde was a little more roundabout. A resident of Taos, New Mexico and married to a Mexican (after two earlier marriages to Arapaho and Cheyenne women), the former mountain man and renowned scout was the best known person in the territory. Born in Missouri in 1809, Kit had moved to Nuevo Mexico, settling in Taos in 1826. Over the next years he trapped, hunted and traded all over the west, from Wyoming and Montana to California. One journey, that would play a role in the events of 1846, was an 1829 trip as a member of a trapping party led by Ewing Young which became one of the first groups to travel cross country from Nuevo Mexico to California.

(Josefa Carson and their son)

(Josefa Carson and their son)His national renown came about from a chance meeting with John C Fremont on a Missouri River steamboat in the summer of 1842. Fremont, an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was preparing an expedition to map the Oregon Trail as far west as South Pass in Wyoming. Fremont, an ambitious self-promoter, recently married to the daughter of Senate Democratic leader Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri (who, before becoming an ally of President Andrew Jackson, had, in 1813, engaged the future president in a pistol gunfight at a Nashville tavern), immediately hit it off with Carson and asked him to join the expedition as a scout.

Carson would serve as scout on each of Fremont's three journeys of exploration. The first was the successful five month trip to South Pass. The second made both Fremont and Carson famous. They traversed the Oregon Trail to the Columbia River with a side trip to the Great Salt Lake. They then made an illegal trek to California and were saved from suffering from the bad weather in the Sierra Nevada mountains by Carson's wilderness acumen. Expelled from California by the Mexican Governor they returned to the U.S. Fremont's well publicized report on their travels gave Carson copious credit but one event he recounted gained particular notoriety. At one point they came across two Mexicans (a man and boy) in the Mojave Desert who were survivors of a groups ambushed by Indians who had killed the men as well as women (after raping them) and stealing all their horses. Carson and one other man went after the killers, tracking down and killing two of them, recovering the horses and returning them to their owners. Although the first dime novel portraying Carson was not published until 1847 (see below, depicting the incident in the Mojave), it was Fremont's report in 1844 that made Kit famous and earned Fremont the nickname "The Pathfinder".

(from wikimedia)

(from wikimedia)The third expedition began in the summer of 1845, initially taking Fremont and Kit back to Oregon. They then proceeded into California, still under Mexican rule and possibly in accordance with secret orders from the Polk administration which sought to annex the area. Expelled once again, they returned to Oregon, returning to the state with the onset of war and organizing a revolt of American settlers which soon took control of the state. Fremont, eager to get the news to Washington, asked Kit to carry dispatches across the country, which Carson promised to do in sixty days. Twenty-eight days out he met Kearny.

Carson's news was startling. California was already under American control. Kearny pondered the news and quickly reached a decision. His orders were to proceed to California and he would fulfill them. However, since he was increasingly worried about reports of the unruly Navajo and anticipated no military action on the west coast, he sent most of his three hundred dragoons back to Santa Fe, only retaining one hundred for the next stage of his expedition.

He sent a note to back to Santa Fe notifying them of the change of plan:

I this morning met an Express from Upper California to Washington city, sent by Lieut.Col. Fremont, reporting that the Americans had taken possession of that department, in consequence of which I have re-organized the Party to accompany me to that country as well be seen by Order No. 34, herewith enclosed.And what better use could he make of the surprising appearance of the best known guide in the southwest? Kearny ordered Carson to lead his men back to California, while he would arrange for someone else to get the dispatches to Washington. Carson briefly thought of disobeying. He'd not seen his wife and family in nearly two years and hoped to spend one night with them in Taos on the way to the east coast and he felt an obligation to keep his word to Fremont and Stockton. He later described his feelings (according to Hampton Sides in Blood and Thunder; the book to read about this era in the southwest):

I was pledged to them and could not disappoint them, and besides that I was under more obligations to Captain Fremont than any man alive.He finally agreed to accompany Kearny, or as Kit later put it, "Kearny ordered me to join him as his guide. I done so." His decision gained the admiration of Kearny's officers, one writing:

He turned his face to the west again, just as he was on the eve of entering the settlements, after his arduous trip and when he had set his hopes on seeing his family. It requires a brave man to give up his private feelings thus for the public good; but Carson is one such! Honor to him for it.(Kearny's route, from The West Point Atlas of American Wars)

Kearny, Carson and the dragoons proceeded south, turning west on October 15, near the modern-day town of Truth Or Consequences. Reaching the headwaters of the Gila River in western New Mexico five days later, they followed it through Arizona (through the present day towns of Safford and Florence, and south of Globe and the Phoenix area, none of which were settled at the time), finally reaching the Colorado River, south of present day Yuma, on November 22. I've visited the pass over which Kearny's men struggled southeast of Globe (photo below).

Four days out of Valverde, Kearny agreed with Carson that his supply wagons were slowing the column down and sent them back to Santa Fe, packing everything on mules, except for two howitzers the general insisted on taking. Even without the wagons it was tough going. One officer wrote of a day on the route in Arizona:

I shall not attempt to describe the route we have passed over today. I have no language to convey even a faint idea of it. Could we have foreseen so much difficulty it would have been better to have retraced our steps 20 miles, to have taken another and more practicable route. From the moment of starting until we dismounted at our present camp, our poor animals were stepping over and among rock of great size - some fixed, but most of them loose, and then the steep hills and gullies were very frequent.Their horses and many mules died. Most of the time the men walked. Both animals and men grew short of food. One officer wrote: "Twere better for it to be blotted out from the face of the earth. It is the veriest wilderness in the world. . . ", and later observing that "Invalids may live here when they might die in any other part of the world, but really the country is so forbidding that no one would scarcely be willing to secure a long life at the cost of living in it."

The starving troopers found some succor when they entered the irrigated lands of the friendly Pima Indians, near present day Phoenix and were able to obtain fresh food.

One of Kearny's assignments was to find a viable passage for road and railroad to California and in his official report of December 12, 1846, written after reaching San Diego, he noted:

This River (the Gila) more particularly the Northern side, is bounded nearly the whole distance by a range of lofty Mountains, & if a tolerable waggin Road to its mouth from the Del Norte is ever discovered, it must be on the South side & therefor the boundary line between the U. States & Mexico should certainly not be North of the 32°of lat. the country is destitute of timber, producing but few cotton wood & mesquite trees, & tho' the soil on the bottom lands is generally good, yet we found but very little grass or vegetation in consequence of the dryness of the climate & the little rain which falls here - The Pimo Indians who make good crops of wheat, corn, vegetables & irrigate the land by water from the Gila, as did the Aztecs (the former inhabitants of the Country) the remains of whose sequias or little canals were seen by us, as well as the position of many of their dwellings, & a large quantity of broken pottery & earthen ware used by them -Elsewhere Kearny wrote of the lands he'd traversed, "It surprised me to see so much land that can never be of any use to man or beast".

Crossing the Colorado, Kearny and Carson entered California, but as tough and exhausting as their march had been so far, their difficulties were only beginning, as they situation was much different than what they expected; California was in chaos. Between contention over American military leadership between Fremont and Navy Commodore Stockton, overconfidence and ineptness in their occupation, they enabled the Mexican population to regroup and, with some military reinforcements, to retake much of the state. Kearny could have used those 200 troopers he sent back to Santa Fe.

After climbing 3,000 feet out of the Imperial Valley and into the hills as they approached the California coast, the weary men were confronted by well-trained Mexican lancers on horses. On December 6, Kearny and his men were battered by the lancers, losing 18 dead and seven severely wounded (Kearny being one of them), ending up surrounded on a hilltop. It was Kit Carson to the rescue as he made a daring nighttime escape through the Mexican lines, making his way to San Diego and Commodore Stockton after walking barefoot for thirty hours without food or water. A relief force was sent which rescued Kearny. Kit stayed behind, unable to walk for a week because of the condition of his feet.

On December 12, 1846, General Kearny entered San Diego, completing the 1,900 mile march of the Army of the West, one of the greatest accomplishments in American military history.

Kearny, Stockton and Fremont were able to cooperate in defeating the Mexican forces and reoccupying the entire state but thereafter fell out in a long and dreary dispute which ended up in Kearny sending Fremont back to Washington to be court-martialed, from which he was saved by his political connections.

Kearny served as military governor of California, returning to Washington in 1847 to a hero's welcome and then serving as governor of Veracruz and Mexico City before the signing of the final peace treaty. Unfortunately he contracted yellow fever in Veracruz and returned to St Louis, dying in 1848.

Fremont recovered from his tumultuous adventure in California to become a leading abolitionist and, in 1856, the first Republican Party candidate for President.

Kit Carson went on to have many more adventures. He was a well-respected Indian agent in New Mexico and continued to do tracking. A Union man when the Civil War started, he became commander of 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry and helped to defeat the Confederate invasion of New Mexico in 1862. He also led his troops in the 1864 Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle, fighting Commanche, Kiowa and Apache, one of the largest conflicts between American troops and Indians on the Great Plains.

He also, with misgivings, led the campaign to force the surrender of the Navajo and their transport from their sacred lands to a reservation on the eastern border of New Mexico. Kit then became one of the important voices for allowing them to return to their lands along the New Mexico/Arizona border, which finally occurred in 1868, the same year Carson died.

He always remained a quiet, soft spoken man, embarrassed by his illiteracy. William Tecumseh Sherman met him while in California during 1847:

"His fame was then at its height, ... and I was very anxious to see a man who had achieved such feats of daring among the wild animals of the Rocky Mountains, and still wilder Indians of the plains ... I cannot express my surprise at beholding such a small, stoop-shouldered man, with reddish hair, freckled face, soft blue eyes, and nothing to indicate extraordinary courage or daring. He spoke but little and answered questions in monosyllables."How odd it must have felt for such a man to become a dime novel hero. In 1849 he tracked a woman (Ann White) and her infant daughter, kidnapped by the Apaches who had murdered her husband and others in a wagon train. He found the horribly abused woman dead, with an arrow in her heart and daughter gone, never to be seen again (it was later learned the Indians killed the baby shortly thereafter). In the Indian camp he also discovered a dime novel featuring him on the cover; the first time he'd ever seen himself in print. Carson remained haunted that the woman "had read the same ... [and prayed] for my appearance that she might be saved", feeling always that he let her down.

Monday, May 23, 2016

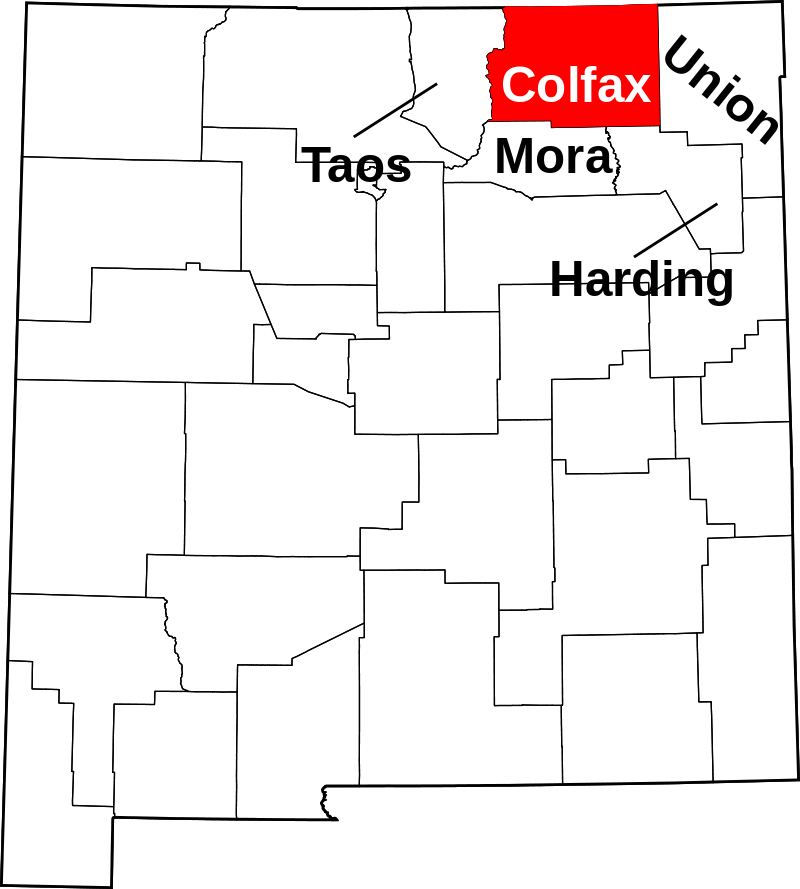

The Colfax County War

Methodist Reverend Parson Franklin J Tolby was well-liked in the Cimarron area of northeast New Mexico so a lot of folks were shocked when his body was found in Cimarron Canyon on September 14, 1875. He'd been shot in the back. Suspicion fell on Cimarron's new Constable, Cruz Vega. On the evening of October 30, a masked mob led by Clay Allison (today remembered as one of the most deadly gunfighters of the 19th century West), seized Vega and lynched him. Two days later, Allison gunned down Vega's friend, Francisco "Pancho" Griego, during a confrontation in a local saloon. More violence was to follow. A lot more.

On our road trips, THC and Mrs THC enjoy learning about the history of the areas we drive through. Often, as we pass a town or site of interest, whomever isn't driving will look it up on Wikipedia. While traveling I-25 in New Mexico and Colorado (and, by the way, the stretch of Interstate from Santa Fe to Denver with the Rockies on your left and the Great Plains on the right is gloriously scenic) a small reference in the Wikipedia entry on the town of Cimarron, New Mexico (present day population, 1021) led us to discover the tale of the Colfax County War, a violent, 15-year confrontation between landowners and squatters that took up to 200 lives and culminated in a decision by the United States Supreme Court.

The origins of the war go back to the days when Mexico governed the province of Nuevo Mexico. It starts with Charles H Beaubien, born in Quebec in 1800, who emigrated first to the United States and then to New Mexico, arriving there in the early 1820s, shortly after Mexico gained its independence from Spain. Settling in Taos, he applied to become a Mexican citizen and in the process his first name was recorded as Carlos, a name retained in all of his future records. Beaubien married Maria Paula Lobato . Scrambling to make a leaving during the governorship of Manuel Armijo, who placed discriminatory taxes on non-native Mexicans, Beaubien was able to enlist the governor's secretary, Guadalupe Miranda, in a scheme to obtain a land grant in northeast Nuevo Mexico. In 1841 the partners were successful in obtaining a grant of 1.7 million acres on the Great Plains, east of the Sangre de Christo Mountains (various sources claim that grants of more than 90,000 acres were not permitted under Mexican law).

Settlement of the grant was delayed by several years. First, by invasions from the new Republic of Texas, which claimed that its western border extended to the Rio Grande. The largest of these, while "unofficial", resulted in a Texian force being captured by Mexican troops. Second, by the American-Mexican War of 1846-8, in which Nuevo Mexico was conquered by the American army.

Beaubien weathered the transition, being appointed to the new American territory's Supreme Court and having his grant confirmed by the peace treaty. As for Miranda, after the war he left the territory and became mayor of Juarez in Mexico.

Lucien Bonaparte Maxwell was born in Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1814. At a young age, he went west and became a fur trapper and trader. He also served as chief hunter for John C Fremont's 1841 expedition of exploration through the Rockies, a journey on which he met and became fast friends with Kit Carson. Kit and Lucien settled in Taos and in a dual ceremony in 1844, Maxwell married the daughter of Carlos Beaubien and Carson the daughter of another prominent local family.

In the 1850s, Lucien Maxwell took on the active management of the land grant (now referred to as the Maxwell Land Grant) and, when Beaubien died in 1864, he inherited his share of the grant (in 1858, Miranda had sold his share of the grant to Maxwell for $2,745). According to most sources the Maxwell Land Grant was one of the three largest contiguous property holdings in American history.

In 1870, Maxwell sold the grant to financiers from Chicago representing British investors for the sum of $1,375,000 and retired to Fort Sumner, New Mexico where he died in 1875 (six years later, Sheriff Pat Garrett shot and killed Billy the Kid at Maxwell's Fort Sumner home, then owned by his son).

What did the new investors find when they took possession? Lucien Maxwell, moved to the settlement of Cimarron sometime in the 1850s (the town was formally chartered in 1859). While he sold some parcels, there were an increasing number of squatters; miners and farmers of Anglo, Spanish and Indian origin and given the size of the grant, Maxwell was pretty casual about enforcing his property rights. The number of squatters accelerated with the 1866 discovery of gold on Baldy Peak which quickly led to the founding of the boom town of Elizabethtown which had a population of 7,000 within a year. Both the town and the gold fields were within the land grant. In 1869, Colfax County was created by carving off an portion formerly belonging to Taos County and Elizabethtown became the county seat.

Unlike Maxwell, the new owners wanted to establish their property rights. The initial attempts by the Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company to assert its rights were a failure. With the assistance of the Territorial Attorney General, eviction notices were served but mostly ignored.

Before going further, let's take a moment to sort out the players on the ownership side. While the original investors were British, the company was eventually taken over by Dutch investors. At some point, Stephen Benton Elkins was installed as president of the company. Elkins was a big figure in New Mexico history. From 1867 to 1877 he served as Territorial Attorney General, US District Attorney, Territorial Delegate to Congress, as well as maintaining a law practice and becoming president of the Santa Fe National Bank. Along with a couple of associates he formed what became known as the Santa Fe Ring, which, through its manipulation of the territorial judicial process was able to control some of the old Spanish and Mexican land grants and play a major role in triggering both the Colfax Country and Lincoln County Wars (it was the latter, taking place from 1878-81 in which Billy the Kid attained national fame). In later life, Elkins moved to West Virginia, became Secretary of War in President Benjamin Harrison's administration and served as Senator from the state from 1895 until his death in 1911. [Note: The ownership trail and the role of Elkins and the Santa Fe Ring remain disputed; if you read ten accounts they will give you ten different versions of the story - THC has chosen to simplify it as best he can].

(Elkins, wikipedia)

(Elkins, wikipedia)The Territorial Attorney General to whom the land company turned for assistance was a friend and business associate of Elkins. The attempts to serve eviction notices in the squatter stronghold of Elizabethtown backfired, provoking a riot and leading the Territorial Governor to call for federal troops to restore order, a request that was ignored.

(Harvesting grain on the Maxwell Land Grant, from tumblr)

(Harvesting grain on the Maxwell Land Grant, from tumblr)However, other means were available. The first was in 1872 to transfer the county seat to Cimarron where the land company was headquartered. A further round of eviction notices followed and, like the first, were mostly ignored, along with more complicated maneuvering, summarized by one source as follows:

At this point the land grant company elected as vice president and COO the chief construction engineer of the Santa Fe Railroad, one William Raymond Morley. Morley was aware that the grant company controlled the key right-of-way over Raton Pass and he took a leave of absence from the railroad to try to strengthen the relationship between the land grant and the railroad. Aware of the impasse between the land grant company and the squatters, Morley requested his friend, Frank Springer, of his native Iowa, to come and help sort out the problem. Springer was a brilliant, analytical and honest attorney. He became one of the most respected of the territorial pioneers. He and his brother Charles founded the CS Ranch, which is still owned and operated by their descendants.Scattered violence was already taking place, but it was the events of 1875 that ignited the War.

In 1874, ignoring the 1860 Act of Congress, the Federal Department of the Interior declared the land grant to be public domain. At about the same time, the Maxwell Land Grant Company defaulted on their property tax obligations. A public auction was held and Melvin Mills, an associate of Thomas Catron, bought the property for $16,479 in back taxes, intending to sell it to Catron for $20,000. When this plan was exposed, the Dutch owners raised enough money to redeem the property. And exposure of this plan shed light on the “Santa Fe Ring,” a secret Republican coalition designed to control public offices in New Mexico, especially the judiciary.

Widely suspected as members of the Ring were Stephen Elkins, Dr. Robert Longwill, Melvin Mills and Thomas Catron (who, by then, was no longer the Territorial Attorney General). When they became aware of possible hidden motives, Morley and Springer founded The Cimarron News and Press, a newspaper which regularly criticized the Santa Fe Ring. This got both men marked for assassination.

Rev. Tolby had arrived in Colfax County and ministered to its population, becoming an advocate for many against the land company and the Santa Fe Ring. In July 1875, letters were published in the New York Sun, denouncing the Ring and naming Elkins, Catron and local judge Joseph Palen as key members. Tolby was suspected to be one of the authors. In early September, Rev Tolby publicly criticized Judge Palen and a local grand jury for failing to indict Pancho Griego for the killing of two soldiers. Later that month, while riding from Cimarron to Elizabethtown, Tolby was shot twice in the back in an ambush.

As related above, Cruz Vega was suspected of the murder, seized and hanged, but before that he was tortured and implicated Manuel Cardenas as an accomplice (Cardenas was killed on November 10) followed by the shoot out in which Clay Allison killed Griego.

Clay Allison already had a reputation as a dangerous man. In 1870 he led an Elizabethtown mob in attacking a jail and seizing and lynching a prisoner and in 1874 had killed another well known gunfighter, Chunk Colbert. The year after shooting Griego, Allison shot and killed Constable Charles Faber of Bent County, Colorado. Eventually relocating to Dodge City he is also alleged to have had a confrontation with Wyatt Earp, though that may just be a piece of Western myth (for more on that legendary cowboy town read The Dodge City Peace Commission).

The violence and legal maneuvering continued over the next decade. At one point, the land company recruited Bat Masterson's brother, James along with 35 enforcers to handle evictions and even got the governor to briefly give them militia status! In the meantime, the county seat was transferred yet again in 1881 to the new town of Springer.. In 1885, the lawn of the new country courthouse in Springer was the site of yet shootout that left two men dead.

The legal aspect of the dispute reached the Supreme Court in 1887 with the court hearing four days of oral argument. The case centered on whether the land grant was valid since there was evidence that the size of the grant far exceeded that allowed under Mexican law at the time. At the same time the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago, ending the Mexican-American War, as well as the 1860 Act of Congress declared the grant valid. The Court, Justice Miller writing on its behalf (United States v Maxwell Land Grant Co., 122 U.S. 365), found that the grant was indeed valid and noting in conclusion :

The case itself has been pending in the courts of the United States since August, 1882, and, on account of its importance, was advanced out of its order for hearing in this court. The arguments on both sides of the case were unrestricted in point of time, and were wanting in no element of ability, industrious research, or clear apprehension of the principles involved in it. The court was thoroughly impressed with the importance of the case, not only as regarded the extent of the grant and its value, but also on account of its involving principles which will become precedents in cases of a similar nature, now rapidly increasing in number. It was therefore given a most careful examination, and this petition for a rehearing has had a similar attentive consideration. The result is that we are entirely satisfied that the grant, as confirmed by the action of congress, is a valid grant; that the survey, and the patent issued upon it, as well as the original grant by Armijo, are entirely free from any fraud on the part of the grantees, or those claiming under them; and that the decision could be no other than that which the learned judge of the circuit court below made, and which this court affirmed.With the Court's decision most of the remaining squatters settled with the company or left. The last casualty was rancher Richard Russell, killed by company enforcers in 1888.

The gold was running out in Elizabethtown by the 1890s. Today it's a ghost town.

Wednesday, February 3, 2016

Forgotten Americans: Henry Lafayette Dodge

. . . to read about some other Forgotten Americans, go here.

(from redstone tours)

(from redstone tours)

In Blood And Thunder, his splendid account of the life of Kit Carson and the mid-19th century conflicts in the American southwest, Hampton Sides chronicles the story of the Navajo as they fought the Spanish, other tribes, and finally the Americans, after the occupation of New Mexico by General Stephen Kearny in 1846. For most of the next twenty years, the relationship between the United States and the Navajos was troubled, but Hampton noted one exception:

HL's grandfather, Israel Dodge, and his brother, John, emigrated west from Connecticut in the late 1770s, eventually making their way to Kaskaskia along the Mississippi River in modern-day Illinois. A rough, small settlement with a substantial percentage of French population, Kaskaskia was isolated in the surrounding wilderness. The Dodge brothers were ambitious, rowdy and occasionally lawless as they sought their fortunes. Under the Treaty of Paris (1783), the area became part of the new United States but by the end of the decade the Dodges had worn out their welcome in Kaskaskia and relocated across the river to Saint Genevieve in the Spanish territory of Missouri (in the 1790s, the two towns were on the opposite side of the Mississippi but the river has since shifted its channel, leaving both on the west bank).

Israel's son, Henry Dodge, who'd been left behind in Kentucky with Henry's wife, rejoined his father in the early 1790s. Israel and young Henry prospered under the Spanish and, after the territory became part of the United States in 1803 with the Louisiana Purchase, became mine and property owners as well as public officials. Henry was a lowly recruit in former Vice-President Aaron Burr's conspiracy to detach the new Louisiana territories from the United States. Upon hearing of President Thomas Jefferson denunciation of Burr's actions as an act of treason, Henry deserted Burr though he was subsequently indicted as a participant though the charges were eventually dropped (for more on this strange, and still controversial, episode see The General Was A Spy). Three years later, in 1810, Henry Lafayette Dodge was born. HL never liked his given middle name (selected by his father in honor of Marquis de Lafayette; as a young soldier, Israel Dodge and Lafayette had both been wounded at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777; for more, read Lafayette's Tour) and never used it once he'd left Wisconsin; although he is now often referred to as Henry Linn, during his time in New Mexico he was known as Henry L.; Linn was the last name of his father's half brother, Lewis Fields Linn (d. 1843)).

Henry Dodge became a general of the Missouri militia during the War of 1812. However, during the 1820s, the family's financial fortunes suffered and, in 1827, Dodge moved the entire family, including HL, to the booming river town of Galena, Illinois (a 20-day upstream journey by keelboat), leaving behind a mountain of debt. (keelboat, from steamboat times)

(keelboat, from steamboat times)

Shortly after arriving in Galena, Henry Dodge relocated his family once again into what is today Iowa County, Wisconsin in the southwestern part of the territory. The settlement he founded, along with forty other lead miners, became known as Dodgeville and is today the county seat. In the Black Hawk War of 1832, "General" Dodge commanded the territorial militia, leading them during the final battle of the campaign against the Sauk and Fox Indians in which 22-year old HL served as a lieutenant. Like many frontier wars, it originated in a welter of confusion and misunderstandings. The Sauk and Fox had been driven by the Americans out of Wisconsin and into Iowa, where they were subject to attacks from their traditional Indian enemies. Desperate to escape their tormentors and return to their homeland, about 1,300 tribe members recrossed the Mississippi triggering a war. Quickly realizing their dreams of a return would not be realized the Indians attempted to surrender but their efforts were not understood and they were violently repulsed. Massacres occurred on both sides, climaxing in a final battle in which the Indians were bloodily defeated, with men,women and children killed. The outcome of the war transformed the Wisconsin territory. At the time of the Black Hawk War there were fewer than 10,000 white settlers. By the mid-1840s the population had grown to 155,000. (from brittanica)

(from brittanica)

In 1833, President Andrew Jackson appointed Henry Dodge commander of the First Regiment of United States Dragoon. Among his junior officers were Stephen Kearny, who would later conquer New Mexico, and Jefferson Davis (who despised Dodge). Three years later, Jackson named Dodge the first governor of the new Wisconsin Territory, a role in which he served until 1841 and then again from 1845 to 1848, when Wisconsin was admitted to the Union and Dodge became its first senator.

(Senator Henry Dodge)

(Senator Henry Dodge)

In the same year, HL married Adele Bequette, whom he had known in Saint Genevieve. It was also becoming clear that, for reasons that remain unclear, Henry Dodge had selected HL's younger brother, Augustus, as his political heir and began grooming him for higher things, though HL continued to look after the family business interests. August Caesar Dodge became Iowa's first territorial delegate to the U.S. Congress and then one of the state's first two senators after its admission to the Union. Augustus Caesar and Henry Dodge are the only father and son to serve in the U.S. Senate at the same time.

HL and Adele soon started a family, having four children and, from 1838 through 1843, HL served as postmaster at Dodgeville, along with running an inn and store in the town (the post office was housed in the store - synergy!). Like his father and brother, HL was active in Democratic party politics and in 1843 was elected Sheriff of Iowa County, uneventfully holding the office until December 1844 when he became clerk of the U.S. District Court for Iowa County.

Then, in May 1846, HL Dodge vanished from Wisconsin, leaving his wife and children, never to see them again. His presence is next documented on August 28, 1846 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, when Stephen Kearny, in the process of establishing a civil administration for the newly conquered territory announced:

Kearny's Army of the West did not leave until the end of June, 1846, giving HL plenty of time to make the journey from Wisconsin and join the expedition. It is very possible HL carried a letter from his father to Kearny. HL did not enlist, nor is he shown on any roster of teamsters so it is uncertain in what capacity he accompanied the 2,000 man army on its journey across the Great Plains, a great feat of logistics, planning and leadership by Kearny who later in the year, accompanied by a little more than 100 dragoons, undertook an epic journey, guided by Kit Carson, across the southwest desert to San Diego, a trek which THC will feature in a post on October 6, 2016.

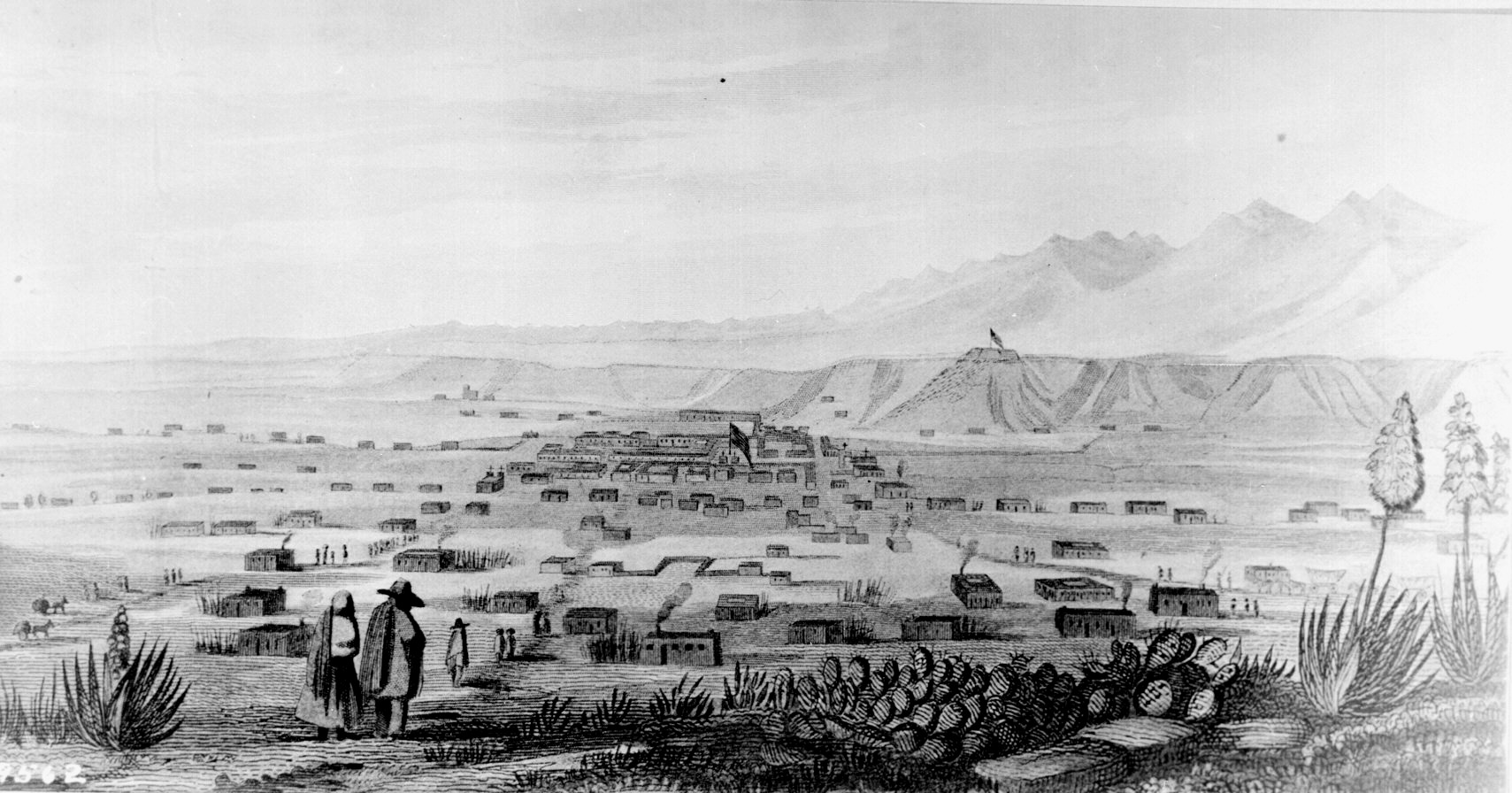

Kearny was able to occupy Santa Fe without a fight, entering on August 18 and quickly moving to establish civil government, leading to HL Dodge's appointment.

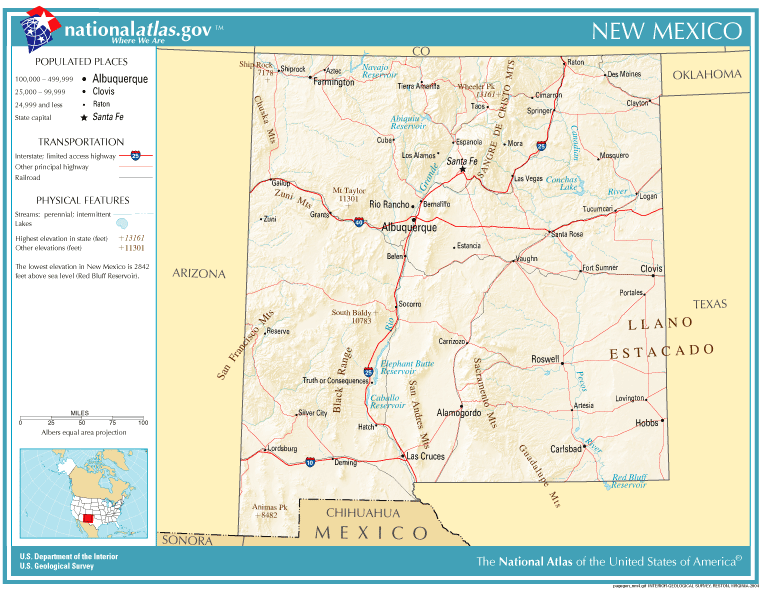

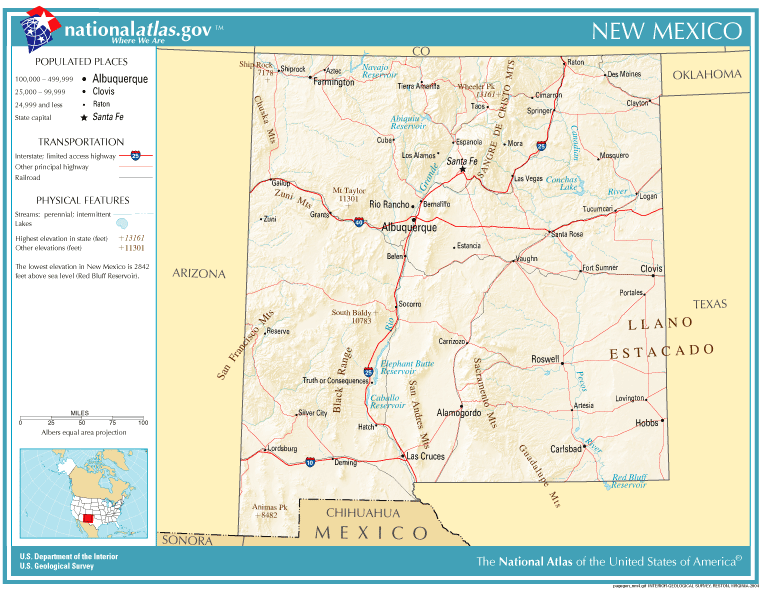

The world Kearny and the other Americans entered was different from anything they'd seen before. There was the light and blue sky amidst dramatic rock formations with little grass or forest. The Spanish colony (part of the new nation of Mexico since 1821) was in many respects unchanged since its founding in the late 16th century as the second European settlement within the boundaries of what was to become the United States. Isolated by 1,000 miles from the nearest substantial settlements in Spanish Mexico it had existed as a (Nuevo Mexico, with Santa Fe to north) beleaguered outpost, from which at one time the native Pueblos had temporarily expelled the settlers (see Pueblo Revolt). For 250 years, the Spanish (now Mexicans) and Indians had existed in a state of perpetual hostility. To the east were the Comanche who ruled the Great Plains. To the north, south and west, the Apache (Jicarillo, Chiricahua, Mescalero), Utes, Navajo and other tribes. Both sides raided each other for sheep, horses and slaves. Not only did the tribes fight the Mexicans but they were constantly at war with each other.

(Nuevo Mexico, with Santa Fe to north) beleaguered outpost, from which at one time the native Pueblos had temporarily expelled the settlers (see Pueblo Revolt). For 250 years, the Spanish (now Mexicans) and Indians had existed in a state of perpetual hostility. To the east were the Comanche who ruled the Great Plains. To the north, south and west, the Apache (Jicarillo, Chiricahua, Mescalero), Utes, Navajo and other tribes. Both sides raided each other for sheep, horses and slaves. Not only did the tribes fight the Mexicans but they were constantly at war with each other.

(This map of present day New Mexico can serve for orientation. During the 1840s & 50s, settlements were strung out from around Taos in the north through Santa Fe and Albuquerque and further south along the Rio Grande, which roughly follows I-25 from Santa Fe to the Texas border. The major route to Navajo country follows I-40 west from Albuquerque, and Dodge's initial trading post at Ciboletta was about where the I-40 icon is located. Fort Defiance was located just north of where I-40 enters Arizona.)

(map via wikimedia)

The largest and most feared of the tribes were the Navajo, with an estimated population of 10-12,000, , having settled in the area perhaps 400 years earlier after having traveled south along the front of the Rocky Mountains from the northern plains. Unlike their counterparts on the Great Plains, the Navajo were a pastoral people herding large flocks of thousands of sheep, cultivating crops, including large orchards of peach trees in the Canyon de Chelly in the heart of their homeland, which covered all of central and northern New Mexico, west of the Rio Grande, northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah, and living in semi-permanent dwellings. Like most tribes, they were very loosely organized with no formal governing structure, a situation incomprehensible to the Americans they were soon to encounter.

(Navajo hogan, from wikicommons)

The living conditions for the Mexicans were primitive even by the standards of frontier Americans. As Sundberg writes:

The next decade saw a constant series of crises between the Americans, the Mexicans and the tribes brought on by raids, random murders, kidnapping for purposes of slavery, rustling and every kind of unruly activity. Things got bad that in 1852, the commander of the American garrison wrote the Secretary of War recommending, according to Sundberg:

This was the situation in which Henry L Dodge found himself (once in New Mexico he never used his middle name of Lafayette). On July 15, 1847 he enlisted as a private in the Santa Fe Battalion of Mounted Volunteers. In enlistment papers he is described as 5'9", with a florid complexion, gray eyes, dark hair and his occupation as lawyer.

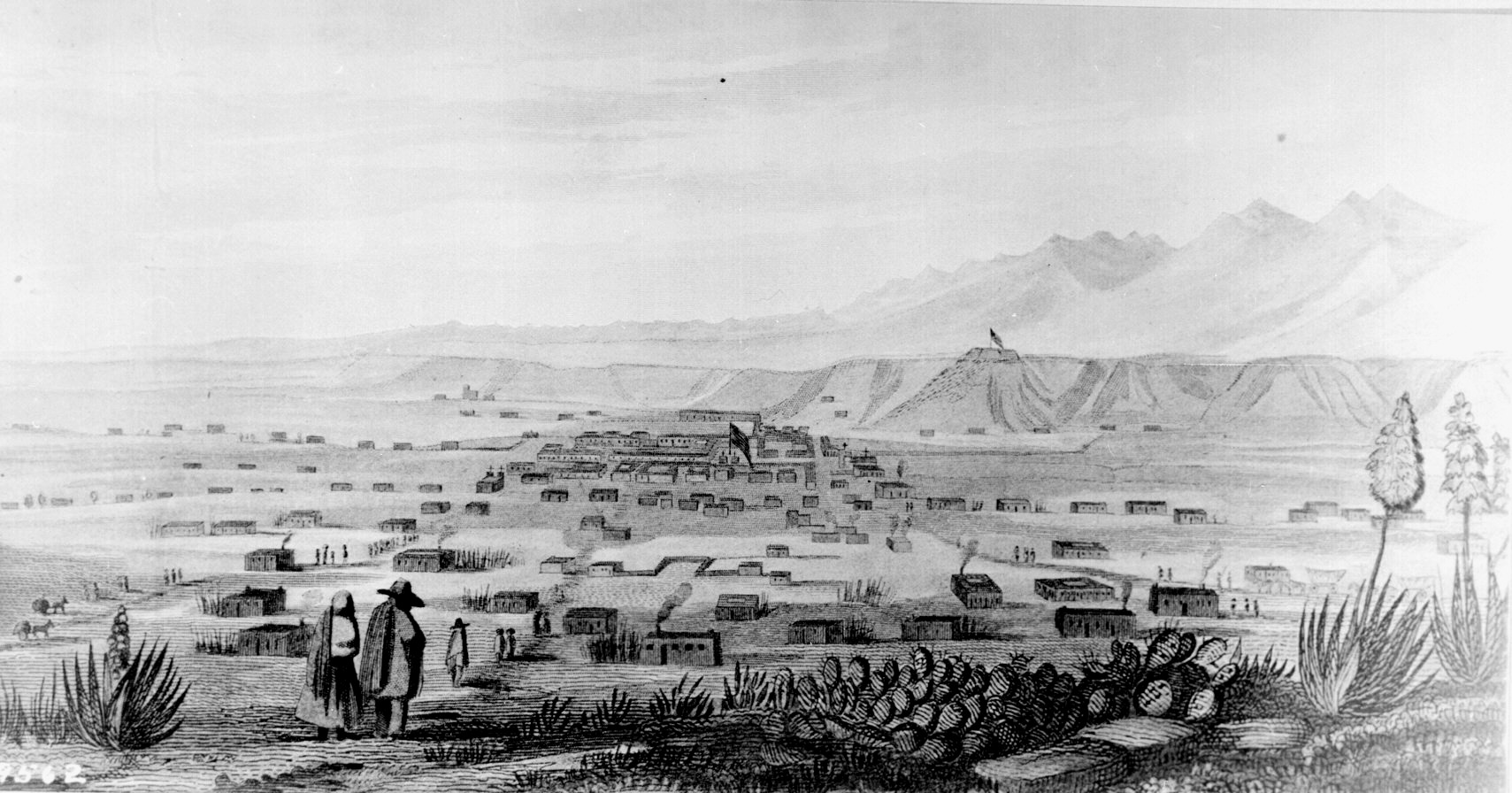

(Santa Fe, 1840s, from wikimedia)

(Santa Fe, 1840s, from wikimedia)

Based on Sundberg's narrative we can tell a few more things about HL Dodge; he was smart, had a sense of humor, an easygoing and open personality, was good with languages, quickly learning Spanish and passable Navajo, seemed less burdened with some of the common prejudices of the day, and liked the ladies.

After serving in Santa Fe and Taos, Dodge was discharged on August 28, 1848. In November he was appointed Notary Public for Santa Fe, a financially lucrative post signaling he had established strong political connections.

By March 1849 he was back in the military as captain of an infantry company composed of sixty men, mostly Mexican. He participated in an expedition that summer against the Ute and Jicarilla in northern New Mexico. While the expedition was underway, a fiasco occurred in which a group of Navajo leaders at a gathering at a military outpost were the subject of an outburst of violence caused by yet another misunderstanding. Several Navajos were killed, including Narbona, the 80 year old senior headman of the tribe. Lodge was involved in trying to prevent this event from triggering a war and in September the Navajo agreed to another treaty. HL was the only American commended in report to the U.S. Commissioner for Indian Affairs.

A few weeks after being mustered out of the army in late September, Dodge was appointed Quartermaster and Commissary agent for a new army outpost at Ciboletta, about 50 miles west of Alburquerque, near the Laguna pueblo. His job was to find and procure supplies for the dragoons stationed in the remote outpost and it served as his primary base until 1853.

Dodge was a wanderer and from Ciboletta he could indulge himself while fulfilling his trading and commissary obligations. It also gave him an opportunity to get to know the Navajo. At Ciboletta he lived with Juana Sandoval by whom he had two children. As his reputation for fairness grew, he was often called in to mediate disputes among the tribes and between the Americans, Mexicans and Indians.

(Mangas Coloradas, Apache, from townnews.com)

(Mangas Coloradas, Apache, from townnews.com)

Dodge was even able to establish a relationship with Mangas Coloradas, the great chief of the Chiricahua Apache and helped broker a peace between the tribe and the Americans in 1852. By the following year, the beleaguered U.S. civilian and military leaders, with the likely encouragement of Wisconsin Senator Henry Dodge, decided to appoint HL Dodge as Indian agent for the Navajo, the pueblos of Azuni, Laguna and Acoma and the seven secluded towns of the Hopi. Dodge's agency covered 79,000 square miles, an area the size of Nebraska. It was quite a challenge, since the Navajo and the other tribes were enemies of long standing though Dodge was to spend almost all his time with the Navajo.

Supported by a minimal budget, an Indian agent's role was to represent the government to his Indian charges and vice versa, encouraging the tribes to abide by their agreements and to provide them with promised supplies. Most agents did not reside with their tribes and saw it as a potentially profitable opportunity and had no specialized knowledge or affinity for Indians. Dodge would do it differently.

In September 1851, the U.S. army decided it needed to project its power into Navajo country and took a risk in building Fort Defiance, a lonely outpost just across the current day border with Arizona and more than 150 miles from the nearest substantial New Mexican settlement. Its main source for food was the Zuni pueblo, seventy miles away.

(from turtletrack)

(from turtletrack)

(Navajo at Fort Defiance)

Unlike our images of a Western fort surrounded by a stockade, Ft Defiance consisted of several buildings, stables, and a stockade for livestock but was open to the surrounding area. Manned by a garrison of about 190 infantry it was the logical place to house Dodge's agency if his intent was to reside close to his clients.

But that's not what HL did. Feeling confident that his personal relationships with the Navajo were strong, he decided to live amongst them, setting up his agency about thirty miles northeast of the fort near the Chuska mountains. Those relationships may have been particularly close because according to Navajo lore, Red Shirt (the name they gave him because of his love of red flannel shirts) had taken a Navajo wife who was closely related to headman Zarcillos Largos which made him a kinsman to the tribe. If this had become known to Dodge's American bosses the relationship would have caused a scandal.

Dodge quickly got to work, requesting farming equipment, a constant refrain in his letters. Here's one sent to the superintendent for Indian Affairs in the territory in the spring of 1855:

(Navajo silversmith Jim Wilson, from Tusconweekly)

(Navajo silversmith Jim Wilson, from Tusconweekly)

A lot of his work was done from the saddle, riding more than 1,000 miles in his first three months on the job (July-Sept 1853). He was busy crossing Navajo country to collect thousands of stolen sheep and horses that the tribe had agreed to return to the settlements along the Rio Grande as well as negotiating a peaceful settlement to a dispute between the Navajo and the Jicarilla Apache.

While Dodge was successful at keeping the peace he was notoriously terrible at writing reports to his superiors and keeping accurate accounts. Often he'd go months between reports and some of the ones he did send contained only one sentence; government audits of his accounts always found deficiencies. He was saved because of the unusual circumstance of having both a territorial governor and superintendent of Indian Affairs who recognized the value of his work, were willing to give him some leeway, and were themselves flexible in their thinking of how best to deal with the Indians.

This was even more true of the man who became Dodge's closest ally, Major Henry Lane Kendrick, commander of the outpost at Fort Defiance. Dodge and Kendrick worked together well and while Kendrick was a strict disciplinarian he had more sensitivity about the Navajo than any of his predecessors or successors. It was at Kendrick's urging that after a few months Dodge relocated his agency to Fort Defiance.

Together, over the next three years, they were able to maintain the peace. As early as June 1854, the Santa Fe Gazette, a paper which had constantly called for ejecting the Indians from the area, noted:

The kidnapping of children, which had gone on for centuries, was a particular sore point for both parties. New Mexicans insisted that the Americans ensure by treaty that the tribes return their kidnapped children, yet resisted returning the Indian children they had kidnapped (a significantly higher number than those held by the Indians). Dodge was, for the first time, able to obtain the release of some Navajo children.

All this occurred while the army was fighting the Jicarilla and Ute in northern New Mexico, making it even more important to maintain peace with the Navajo. The Jicarilla War climaxed in 1854 with two events; the first on March 30 when the Indians inflicted one of the army's worst defeats in the West, attacking sixty dragoons near Taos, killing 22 and wounding 34, followed several weeks later by a successful army attack, guided by Kit Carson, which ended the war.

In November 1856, amidst rumors that the Coyotero and Mogollon Apache were raiding near the Zuni pueblo, Major Kendrick decided to mount an expedition with forty dragoons as a show of strength. He invited Henry to along, and HL, always restless and interested in an adventure, accepted, bringing along a friend, Navajo headman Armijo. Riding south from Zuni, the expedition moved into uplands, a rocky world of mesas and arroyo canyons, dotted with pinon pines and sage.

(Zuni pueblo, late 1800s, from arizonastate)

(Zuni pueblo, late 1800s, from arizonastate)

On the morning of November 19, Dodge and Armijo decided to do some hunting and split off from Kendrick's column, intending to rejoin it later in the day. It was typical of Dodge's casual nature to ride off with only one companion while the dragoons were hunting Apache. They soon shot a deer; Armijo dressed the carcass and volunteered to take it back to the troops. Dodge wanted to do more hunting so the two parted ways. Henry was never seen alive again.

By the next day, when Dodge had still not rejoined the column, Kendrick launched a thorough search, in which Armijo took the leading role, the only thing found were some tracks, clearly indicating that Dodge had encountered Apache but giving some hope that Dodge was kidnapped and still alive. The realization that a large party of Apache had been so close to the dragoons without them having a hint of their existence was a shock.

Efforts were made to contact the Apache in order to ransom Dodge but they were unsuccessful. Two months later remains were found, making it evident Henry had been murdered shortly after encountering the Apaches.

Within a few months of Dodge's death, the entire team that he had worked with was gone. A new territorial governor and superintendent of Indian affairs (who happened to hate all Indians) were appointed. Major Henry Lane Kendrick was also gone by the summer of 1857, leaving to become professor of Chemistry, Mineralogy and Geology at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, NY. Promoted to colonel in 1873, he retired in 1880 and was remembered as one of the most popular professors to ever teach at the academy. In 1885, a Navajo delegation to Washington DC took a side trip to New York City to visit the retired officer whom they greatly respected. The 80-year old Kendrick died in 1891, having caught cold serving as an honorary pallbearer at the funeral of General William Tecumseh Sherman (as did former Confederate General, Joseph E Johnston).

(Henry Lane Kendrick from aztecclub)

(Henry Lane Kendrick from aztecclub)

All of the successors in New Mexico, military and civilian, were to be found wanting in their ability to keep the peace. Several Indian agents for the Navajos were appointed in quick succession with their performance ranging from indifferent to incompetent and none able to establish the personal relationships with the tribe that Dodge had done so effectively.

in 1860, hostilities resumed between the Americans and Navajo. By 1863 the situation was so bad the Americans decided to put an end to it once and for all and sent a large military force under the command of Kit Carson to Canyon de Chelly, the heart of Navajo country. The campaign accomplished its goal by laying waste to the Navajo homeland and forcing the starving Indians to surrender. In the spring of 1864, 9,000 Navajo walked about 300 miles to a small reservation near Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico, well outside of their traditional lands. It was a miserable experience on flat land unsuited to agriculture and eventually the plight of the Navajo drew sympathetic attention from many Americans, including Kit Carson, who wanted them to be allowed to return to their homeland.

(Canyon de Chelly, from launchphotography)

In 1868, yet another treaty was negotiated and the Navajo returned to the New Mexico/Arizona border area under their headman Manuelito, and armed conflicts with the U.S. government ended. The reservation, which has been expanded several times over the years, now covers an area about the size of the state of South Carolina, making it the largest reservation in the country. Navajo Nation, with about 300,000 members, of which 2/3 live on the reservation, is the largest tribe in the United States.

Abandoned by her husband, Adele Bequette Dodge never remarried, dying in 1905. Of her four children with HL, only the eldest had any recollection of their father.

One of HL Dodge's grandchildren from his relationship with Juana Sandoval lived until 1966.

And then there is Henry Chee Dodge, about whom Sundberg provides some fascinating background. Henry Chee, whose mother was Navajo, always claimed his father was Juan Amaya, Dodge's interpreter, who named him in honor of his friend, but there remains a question about whether he was really HL's son by his Navajo wife. From the age of eight, the orphaned Henry Chee was raised at Fort Defiance by mixed Anglo-Navajo families. HL's brother, former senator Augustus Caesar Dodge, took an interest in assuring the child was properly educated at the Fort's school. In 1883, he became patrol chief of the Navajo police force and a year later was appointed by the Indian Agent as head chief of the Navajo Nation after the death of Manuelito. An astute businessman, Henry Chee partnered with an Anglo to establish a profitable trading post in the Chinle Valley or as Raymond Friday Locke puts it in The Book Of The Navajo "Thrifty and well acquainted with the white man's way of doing business, he amassed a considerable fortune" and as council chairman "was shrewd in his dealings with the government", negotiating mining and oil exploration deals that brought substantial monies to the tribe. He also liked the ladies, reputedly having eight wives.

(Henry Chee Dodge, 1885, from Navajo Times)

(Henry Chee Dodge, 1885, from Navajo Times)

(Henry Chee Dodge, 1945, from maguiresplace)

(Henry Chee Dodge, 1945, from maguiresplace)

Elected as the Navajo's first tribal chairman in 1923 and serving until 1928, Henry Chee was reelected to the post in 1942. He died on January 4, 1947.

Henry Chee's son, Thomas Dodge, graduated from St Louis University Law School and took up legal practice in Santa Fe. From 1933 to 1936 he was Navajo tribal chairman and spent the rest of his career working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Dodge's daughter, Annie Dodge Wauneka, was an influential member of the Navajo tribal nation and became the second women on the tribal council, serving twenty seven years, and for three terms was also chairman of the council's health and welfare committee. In 1963 she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. She passed away in 1997.

HL Dodge remains an admired figure by the Navajo. In researching this piece, THC came across many tributes to his work and sympathy for the Navajo. A 2013 article from the Navajo Times summed it up:

In Blood And Thunder, his splendid account of the life of Kit Carson and the mid-19th century conflicts in the American southwest, Hampton Sides chronicles the story of the Navajo as they fought the Spanish, other tribes, and finally the Americans, after the occupation of New Mexico by General Stephen Kearny in 1846. For most of the next twenty years, the relationship between the United States and the Navajos was troubled, but Hampton noted one exception:

"During the mid-1850s there was perhaps only one bright spot in the American-Navajo relationship. For a few brief years a truly competent man held the office of Indian agent to the Navajo people. His name was Henry Linn Dodge, a perceptive young man from Wisconsin who had lived for years in the territory."This brief mention caught the eye of THC and he undertook some research, quickly learning that Henry L (HL) Dodge remains an honored figure by the Navajo tribe to this day. He also found that the first full biography of HL Dodge had been published very recently: Red Shirt: The Life And Times of Henry Lafayette Dodge by Lawrence D Sundberg, a work which took the author twenty years to research and write, and from which much of this account is taken. An anthropologist who taught for many years among the Navajo, and speaks their language, Sundberg is also the author of Dinetah: An Early History Of The Navajo People. Red Shirt is a fascinating read that gives a flavor of life during America's westward expansion. The story of HL and his family is typical of the adventuresome and restless characters who moved constantly westwards during the 19th century.

HL's grandfather, Israel Dodge, and his brother, John, emigrated west from Connecticut in the late 1770s, eventually making their way to Kaskaskia along the Mississippi River in modern-day Illinois. A rough, small settlement with a substantial percentage of French population, Kaskaskia was isolated in the surrounding wilderness. The Dodge brothers were ambitious, rowdy and occasionally lawless as they sought their fortunes. Under the Treaty of Paris (1783), the area became part of the new United States but by the end of the decade the Dodges had worn out their welcome in Kaskaskia and relocated across the river to Saint Genevieve in the Spanish territory of Missouri (in the 1790s, the two towns were on the opposite side of the Mississippi but the river has since shifted its channel, leaving both on the west bank).

Israel's son, Henry Dodge, who'd been left behind in Kentucky with Henry's wife, rejoined his father in the early 1790s. Israel and young Henry prospered under the Spanish and, after the territory became part of the United States in 1803 with the Louisiana Purchase, became mine and property owners as well as public officials. Henry was a lowly recruit in former Vice-President Aaron Burr's conspiracy to detach the new Louisiana territories from the United States. Upon hearing of President Thomas Jefferson denunciation of Burr's actions as an act of treason, Henry deserted Burr though he was subsequently indicted as a participant though the charges were eventually dropped (for more on this strange, and still controversial, episode see The General Was A Spy). Three years later, in 1810, Henry Lafayette Dodge was born. HL never liked his given middle name (selected by his father in honor of Marquis de Lafayette; as a young soldier, Israel Dodge and Lafayette had both been wounded at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777; for more, read Lafayette's Tour) and never used it once he'd left Wisconsin; although he is now often referred to as Henry Linn, during his time in New Mexico he was known as Henry L.; Linn was the last name of his father's half brother, Lewis Fields Linn (d. 1843)).

Henry Dodge became a general of the Missouri militia during the War of 1812. However, during the 1820s, the family's financial fortunes suffered and, in 1827, Dodge moved the entire family, including HL, to the booming river town of Galena, Illinois (a 20-day upstream journey by keelboat), leaving behind a mountain of debt.

Shortly after arriving in Galena, Henry Dodge relocated his family once again into what is today Iowa County, Wisconsin in the southwestern part of the territory. The settlement he founded, along with forty other lead miners, became known as Dodgeville and is today the county seat. In the Black Hawk War of 1832, "General" Dodge commanded the territorial militia, leading them during the final battle of the campaign against the Sauk and Fox Indians in which 22-year old HL served as a lieutenant. Like many frontier wars, it originated in a welter of confusion and misunderstandings. The Sauk and Fox had been driven by the Americans out of Wisconsin and into Iowa, where they were subject to attacks from their traditional Indian enemies. Desperate to escape their tormentors and return to their homeland, about 1,300 tribe members recrossed the Mississippi triggering a war. Quickly realizing their dreams of a return would not be realized the Indians attempted to surrender but their efforts were not understood and they were violently repulsed. Massacres occurred on both sides, climaxing in a final battle in which the Indians were bloodily defeated, with men,women and children killed. The outcome of the war transformed the Wisconsin territory. At the time of the Black Hawk War there were fewer than 10,000 white settlers. By the mid-1840s the population had grown to 155,000.

In 1833, President Andrew Jackson appointed Henry Dodge commander of the First Regiment of United States Dragoon. Among his junior officers were Stephen Kearny, who would later conquer New Mexico, and Jefferson Davis (who despised Dodge). Three years later, Jackson named Dodge the first governor of the new Wisconsin Territory, a role in which he served until 1841 and then again from 1845 to 1848, when Wisconsin was admitted to the Union and Dodge became its first senator.

(Senator Henry Dodge)

(Senator Henry Dodge)In the same year, HL married Adele Bequette, whom he had known in Saint Genevieve. It was also becoming clear that, for reasons that remain unclear, Henry Dodge had selected HL's younger brother, Augustus, as his political heir and began grooming him for higher things, though HL continued to look after the family business interests. August Caesar Dodge became Iowa's first territorial delegate to the U.S. Congress and then one of the state's first two senators after its admission to the Union. Augustus Caesar and Henry Dodge are the only father and son to serve in the U.S. Senate at the same time.

HL and Adele soon started a family, having four children and, from 1838 through 1843, HL served as postmaster at Dodgeville, along with running an inn and store in the town (the post office was housed in the store - synergy!). Like his father and brother, HL was active in Democratic party politics and in 1843 was elected Sheriff of Iowa County, uneventfully holding the office until December 1844 when he became clerk of the U.S. District Court for Iowa County.

Then, in May 1846, HL Dodge vanished from Wisconsin, leaving his wife and children, never to see them again. His presence is next documented on August 28, 1846 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, when Stephen Kearny, in the process of establishing a civil administration for the newly conquered territory announced:

Henry L Dodge is appointed Treasurer of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the place of Francisco Ortis, who, in consequence of sickness, is unable to perform the duties.Why did HL leave Wisconsin, leaving his wife and young children to a life of poverty (though General Dodge did his best to help the family over the years)? In Red Shirt, author Sundberg tries to unravel the mystery. Though HL had business debts and been arrested a couple of times for assault and battery, Sundberg's speculation centers around a sworn deposition given by Andrew J Hewett on May 21, 1846 just after Dodge disappeared. Hewett had sued Dodge for an unpaid debt of $124 and according to Sundberg's summary of the deposition:

He knew for a fact that Henry L Dodge had left Wisconsin and that "he has had very grave and serious family difficulties" and that Adele had "separated from him"'. He also flatly stated that Dodge had left his home "at a late hour of the night taking his clothing with him".Sundberg goes on to speculate, based upon some complicated family history, that what may have driven HL Dodge to leave was his wife's discovery that he had two illegitimate children while they were married. As the author notes:

Political infighting, duels and pummelings, debts and deceptions and fraud; all those peccadilloes were discussed openly in Wisconsin . . . but in the personal letters and in the press one subject was never addressed directly and only alluded to with the most circumspect similes. That was the subject of sex and extra-marital sex.With General Dodge governor of the territory and pushing for statehood amidst his political enemies, a scandal involving his son could have been devastating. Sundberg makes an informed guess that Henry Dodge helped with his son's flight. Stephen Kearny had served under Dodge in the First Dragoons and the two had a good relationship. On May 13, 1846, the United States had declared war on Mexico and, in anticipation, Kearny had earlier been ordered to assemble an army at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, near the Missouri border, with instructions to march on Santa Fe, once war was declared.

Kearny's Army of the West did not leave until the end of June, 1846, giving HL plenty of time to make the journey from Wisconsin and join the expedition. It is very possible HL carried a letter from his father to Kearny. HL did not enlist, nor is he shown on any roster of teamsters so it is uncertain in what capacity he accompanied the 2,000 man army on its journey across the Great Plains, a great feat of logistics, planning and leadership by Kearny who later in the year, accompanied by a little more than 100 dragoons, undertook an epic journey, guided by Kit Carson, across the southwest desert to San Diego, a trek which THC will feature in a post on October 6, 2016.

Kearny was able to occupy Santa Fe without a fight, entering on August 18 and quickly moving to establish civil government, leading to HL Dodge's appointment.