Born in 1757 to a Maryland planter who died when James was six, raised with aspirations to be a gentleman and aristocrat though the family fortunes had suffered with his father's death, Wilkinson made his way to Philadelphia where his charm and spirit began to connect him with the society he felt entitled to be part of. When news reached Jamie of Lexington and Concord he rode to Boston, arriving in July 1775. The new American army was desperate for officers and due to his brief experience with a Maryland militia company he was appointed a Captain in the Second Continental Regiment.

The tale of how that 18 year old youngster eventually became Commander of the United States Army while serving at the same time as a secret paid agent for the Spanish Empire is told in a fascinating book by Arno Linklater, An Artist In Treason: The Extraordinary Double Life of General James Wilkinson (2009).

(Wilkinson from Wikipedia)

(Wilkinson from Wikipedia)Linklater traces the career of a supremely ambitious, calculating and crafty man seeking personal status and financial wealth over a period of fifty years. Serving four Presidents (Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison) as Army Commander he was an inspirational commander with a gift for strategic analysis but his financial incompetence combined with his social striving constantly led him into trouble

Wilkinson's career in the Revolutionary Army ground to a halt after he aligned himself with General Horatio Gates in the Conway Cabal in its failed attempt to remove George Washington as American commander. Along the way, as Chief of Staff to Gates he treated Benedict Arnold disgracefully during and after the Battle of Saratoga, a key incident in Arnold's growing discontent that eventually led to his treason. Deciding to find fortune in the new Western territories, Wilkinson moved his family to Kentucky (then a part of Virginia)in the early 1780s. His conviviality and magnetism drew people to him, allowed him to gain traction in local politics and induced people to easily make him loans. Business scheme after scheme went sour however. In one instance, he was granted the land on which he started the town of Frankfort but due to financial troubles had to sell it only a year before it was named state capitol and land prices skyrocketed.

He eventually settled on trying to open trade on the Mississippi River by taking goods to New Orleans, then ruled by Spain and forbidden to American traders. In 1787 Wilkinson was not only allowed to sell his goods but was proposed and accepted as a secret agent for Spain (known as Agent 13), establishing a cypher system for communication with his new masters not decoded by historians until the middle of the 20th century.

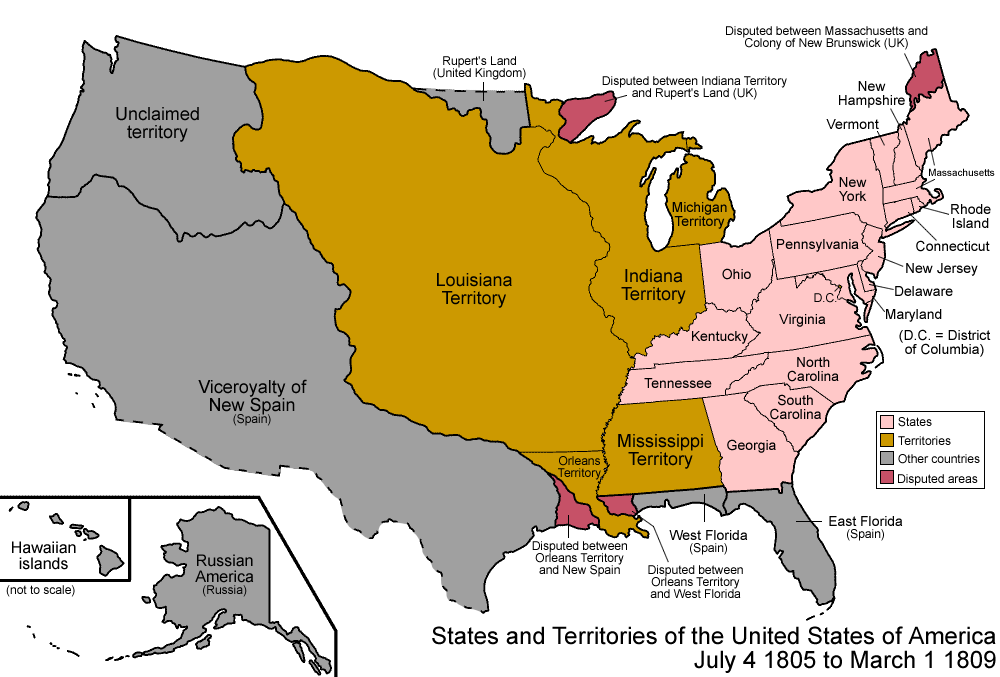

Linklater gives us the background against which Wilkinson's treachery took place. He describes an America in the 1780s and early 90s in which settlers west of the Appalachians were dissatisfied with the government(s) on the other side of the mountains and in which the new concept of "The United States" was not considered a settled matter. The farmers and merchants in Kentucky and Tennessee looked west and south to the Mississippi River and New Orleans as their route to prosperity in the future. As an established figure in Kentucky, Wilkinson held out to the Spanish the prospect of a Kentucky free of the United States and even potentially united with Spain. During his initial work as a spy that is indeed what Wilkinson worked towards though he was ultimately thwarted when Kentucky became a state in 1792.

Wilkinson rejoined the U.S. Army in 1791 in the wake of its bloodiest defeat at the hands of American Indians along the Wabash River in Ohio. Helping to finally subdue the tribes (while continuing to serve as agent for Spain) by 1797 James had become army commander (an army consisting of only 3,000 soldiers) at which time he ceased being a double agent for several years, although continuing some contacts with Spanish officials.

But during those years Wilkinson had provided valuable service to Spain. As Linklater recounts:

Wilkinson had already proved his usefulness in several specific ways. . . . the most valuable results came from the flow of intelligence he provided about U.S. military intentions and capability, and from the insights he offered about how they might be countered. The most obvious example was his recommendation to Miro to build a fort at New Madrid. Its construction immediately curbed U.S. expansion down the Mississippi and encouraged a surge of settlement into what would become Missouri, not just by Anglo-American but by more than a thousand Shawnees and Delawares who were given land . . . 'with a view to rendering us aid in case of war with the whites' . . . the fort became increasingly useful a a jumping-off point for agents and couriers who needed to enter the United States.His value as a spy was appreciated by many. In a memo prepared for Napoleon in 1800 by Joseph de Pontabla, a Frenchman living in Louisiana, he emphasized the influence on Spanish authorities:

In June 1794, Wilkinson passed on General Wayne's plan to rebuild Fort Massac, near the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and strongly advised Spain to counter with an outpost of its own [which it did].

"by a powerful inhabitant of Kentucky, who possesses much influence with his countrymen, and enjoys great consideration for the services he had rendered to the cause of liberty, when occupying high grades in the army of the United States; [but] who . . . has never ceased to serve Spain in all her views"Now enters one of the other great scoundrels of American history, Aaron Burr (who had also been a member of the Canadian expedition during 1775-6). Two centuries later the details of the Burr Conspiracy remain cloudy but at its heart was the seemingly mad plan of the former Vice-President of the United States to carve off the lands west of the Appalachians and lead their citizens on an expedition to seize New Orleans and Mexico, setting up a new country to challenge the United States for leadership. As early as 1797, Burr and Wilkinson were in conversation about the future of the West but it was only after Burr shot and killed Alexander Hamilton in 1804 ending his political career that he came West and set his plans in motion.

By that time, the Louisiana territory had been purchased from France, which briefly owned it after Spain and there was an ongoing border dispute between the United States and Spain regarding the boundary between Louisiana and Texas. War was openly expected on both sides and warmly anticipated by Americans in the west. It remains unclear how open Burr was about his ultimate plans in his discussions and letters with Wilkinson as well as his extensive discussions with other leading Western figures included Andrew Jackson but there is no doubt Wilkinson and Burr were in contact. At the time, Wilkinson was not only the army commander but also the Governor of the Louisiana Territory, one of the only times in American history where the military and civilian roles were combined, making him a critical figure in Burr's plot.

While some of Burr's supporters merely thought they would be joining a Burr filibustering expedition to Mexico in the wake of an American army while others had a different idea; specifically that Wilkinson would concentrate American military on the Louisiana frontier, provoke a war with Spain and invade, leaving New Orleans open for Burr to inspire an insurrection and trigger his plans.

The critical moment was in October 1806 when a Burr letter made it clear that Wilkinson had to choose. Thankfully he chose the United States and informed President Jefferson of the conspiracy; carefully omitting any incriminating information about his prior knowledge. This led to Jefferson informing Congress in early 1807, Burr's arrest, indictment and trial for treason (he was acquitted). On a parallel course, Wilkinson negotiated a peaceful, though temporary, resolution of the border dispute with the Spanish military commander.

It is stunning in light Wilkinson's involvement in the early stages of the Burr conspiracy as well Presidents Washington, Adams and Jefferson all being aware of the many allegations that Wilkinson was a Spanish spy that he was able to remain as army commander until 1813, even as he sought payment from Spain for protecting its empire by revealing the Burr conspiracy! However strange it seems Linklater is convincing in explaining how it happened and the motivations of the Presidents in keeping Wilkinson in place. Wilkinson himself survived three court-martials, including one for being part of the Burr conspiracy, during the course of his career. An amazing story, capped by his last attempt to make his fortune when he went to Mexico City to be an aide to Emperor Augustin of the newly independent country of Mexico and then after Augustin's abdication as a kind of business consultant for Americans with interests in Mexico. He died in Mexico City in 1825.

In writing of this period Linklater reminds us that we should not think of the early American republic as the United States of today. It was not inevitable that it would succeed as it has, nor that it would hold together. He also reminds us that even during that period there is a reason that while the Western territories might have chosen the leave the new country in the 1780s by the time of the Burr Conspiracy a mere fifteen years later there was a much broader pride in being an American that made it unlikely that the scheme could ever succeed. At the same time Linklater brings to life Wilkinson's Spanish contacts and allows us to understand how they viewed him.

Wilkinson was a scoundrel but also insightful. Linklater cites this excerpt from a letter written in 1821 in which he comments on the recent Missouri Compromise, at a time when Wilkinson was a Louisiana resident and a slaveowner:.

"You can not find any one of virtue & Intelligence who, viewing negro slavery in the abstract, & to probable results, will not condemn it as a curse. Yet yielding to Habit, indolence and ease, we approve the curse. The Missourians will discover too late that the opponents to the introduction of Slavery among them were their best friends."It reminds THC of Senator Sam Houston's baleful prediction thirty years later in the wake of the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill (see The Raven):

"[The Union] is the Rock of our political Salvation. The Southerns and Westerns have most to dread from the Catastrophe, yet they are accelerating it by their insatiate desire for limitless domain."

"No event of the future is more visible to my perception than that, if the Missouri Compromise is repealed, at some future day the South will be overwhelmed".

No comments:

Post a Comment