November 8, 1519: Hernan Cortes enters Tenochtilan

"Columbus sailed the ocean blue" in 1492, but for more than two decades the New World (once it was accepted that the lands were not Asia) was an afterthought for Spain. Great riches had not been found and what precious metals had been discovered were disappearing, along with the native population that worked for the conquerors. The major Spanish (or more properly Castilian, the part of the newly united Spain from which most settlers came) presence was limited to the islands of Hispaniola (current day Dominican Republic & Haiti), Puerto Rico, Cuba and Jamaica along with a small, struggling settlement on the mainland in Panama.

The governors of the Spanish islands were constantly on the look out for opportunities to seize new lands and find new wealth. In 1517 and then again in 1518 the Governor of Cuba, Diego Valazquez, sent small expeditions to the mainland to explore the coast north of Panama, seeking treasure and if there might be a passage to Asia. The first expedition ran into disaster in the Yucatan with more than 50 Spaniards being killed. The second expeditionfound evidence that north of the Yucatan there was a culture of more sophistication and wealth than the Spanish had found on the Caribbean islands.

What they saw were the outlying districts of a culture based in central Mexico that was the most complex, prosperous and heavily populated area (between 8 and 10 million) of North America, centered on the central valley that today houses Mexico City. Only a century earlier a tribe had emigrated from somewhere to the north, settling in the valley and seizing control and then began a period of rapidly expansion, creating a tribute empire running from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific and south towards the modern southern border of Mexico. The tribe were the Mexica, often referred to as the Aztecs.

Sending back word of their discovery, Governor Valazquez began putting together a large expedition to learn more about this country and find trading opportunities but without authorization to establish settlements. This was not, in Valazquez's view, an expedition of conquest. To lead it he named Hernan Cortes. Cortes, born in Castille in 1484, emigrated to Hispaniola in 1506. There he caught the eye of Valazquez, then an aide to the governor of the island. In 1511 when Valazquez received permission to lead an expedition to conquer Cuba he named Cortes as an aide. After the conquest Cortes received further promotions.

Cortes was a remarkable man. Brtual and also a great leader capable of inspiring loyalty. He never appears to have lost his self-confidence, at least outwardly, even in the worst of moments and thus was able to keep men following him when they might have otherwise panicked. Throughout his career Cortes also exhibited a good deal of subtlety in his approach, using indirect means when better suited, avoiding confrontation when unnecessary, and able to psychologically dominate many of his opponents.

Hugh Thomas summed it up in his assessment:

The word which best expresses Cortes actions is 'audacity': it contains a hint of imagination, impertinence, a capacity to perform the unexpected . . . Cortes was also decisive, flexible, and had few scruples.All of which proved useful in Mexico.

Cortes organized the expedition with his usual energy and thoroughness on a scale exceeding Valazquez's expectations, consisting of eleven ships and 530 men (a substantial portion of the male Castilian population of Cuba). All of which prompted second thoughts by his mentor who became worried that Cortes might exceed his orders and steal the glory of any new discovery for himself. Although the Governor made half-hearted attempts to stop him, Cortes ignored them and left Santiago, Cuba in November 1518, arriving in the Yucatan in February 1519, and finally in the area near modern Veracruz, Mexico in April.

In his first week in Mexico Cortes observed two things. First, he received emissaries from the Mexico emperor, Moctezuma. The emissaries alternately welcomed and threatened but they also came with presents showing the astonishing wealth of the Mexica. He also heard from several local tribes how much they felt oppressed by the Mexica. With his characteristic decisiveness, Cortes decided to seize the opportunity and march, with Indian allies, from the lowlands to the mile-high Valley of Mexico and meet Moctezuma. Before leaving the coast he established a formal settlement (Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz), in violation of his orders from Valazquez, asserted autonomy from the Governor and scuttled his ships, sending a message to his men that the only outcomes for them were success or death. Cortes kept asking the Mexica emissaries when he could visit Moctezuma but they kept putting him off, claiming the emperor was busy.

In the Mexica capital, Tenochtilan, the arrival of the strangers provoked much discussion and hesitation about what to do. Moctezuma seems to have been a vacillating character, uncertain of himself and others. While some of his counselors urged an attack on Cortes and warned of the danger he posed, Moctezuma would not approve such action.

Having no response from the emperor, Cortes set off with his men in August 1519. Their route took them through the land of the Tlaxcalans, a tribe unsubdued by the Mexica who were also hostile initially to Cortes. After a series of battles in which the Spaniards defeated the Tlaxcalans, they decided to ally themselves with Cortes against their hated enemy the Mexica.

(Route of Cortes from Wikipedia)

On November 8, Cortes entered Tenochtitlan without opposition while receiving greetings from the Mexica nobles as well as the emperor. The Castilians were astonished at the city and indeed the entire Valley of Mexico. Tenochtilan had an estimated population of 200,000; the only Christian European city of the time which might have been as populous was Naples, a place only a couple of the conquistadors had seen. The biggest city most of them had been in was Seville, which may have had 30,000 people. But it was not just the size of the city. Tenochtitlan was orderly, clean, filled with beautiful gardens, large buildings and pyramids, and looked unlike any European city. Set in the middle of a large lake it was connected to a network of smaller cities on the mainland by causeways. a network of cities that were also clean and well organized. The Mexica had also tamed the lake putting in dikes and creating artificial floating islands on which they grew crops.

(Lake of Mexico with Tenochtitlan in center)

The next six months were remarkable, though having read several accounts it is still unfathomable to THC how Cortes did it. Cortes seems to have personally cast some type of spell over Moctezuma who revealed the vast wealth of the Mexica and allowed Cortes to dominate he and his court; by all accounts Moctezuma seemed to genuinely like Cortes, who was studiously polite and engaging in return. On November 14, Cortes effectively kidnapped Moctezuma and his entourage, moving them from the royal palace to the luxurious accommodations Cortes had been given. Moctezuma would issue orders to provide the Spanish with food, jewels and gold and his subjects complied. For his part, Cortes considered Moctezuma still the rightful ruler of the Mexica and someone who had submitted to the greater jurisdiction of the King of Spain. The Castilian had achieved the peaceful submission of a vast and wealthy state.

Despite the apparent peaceful arrangement, there were two areas of contention. The first was the Castilians dislike of the Mexica gods and their efforts to get them to accept Christianity. The second was their horror over human sacrifice, a practice they saw abundant evidence of; the Mexica having on occasion ritually slain thousands of captives, keeping and displaying the skulls. The Spanish made efforts to curb both practices though Cortes was relatively restrained in his efforts. Both the Spanish and the Mexica could be brutal and both were expansionist empires. Mexico was not as idyllic as pictured in Neil Young's Cortez The Killer though it is a great tune anyways; here's an amazing cover version you should listen to.

Although there was grumbling among some of the Mexica noblemen this state of affairs continued until startling news arrived in April 1520.

That month another conquistador, Panfilo de Narvaez, landed at Veracruz with 1300 men carrying orders from Governor Valazquez to find the renegade Cortes and hang him. Cortes actually learned of Narvaez arrival from Moctezuma who was informed by the Mexica's excellent communication network. The Mexica saw a chance to regain control of their destiny and even Moctezuma became more assertive, establishing direct communication with Narvaez.

What followed is another example of Cortes personality traits. He quickly decided to take a good portion of his much smaller force and march back to the coast, leaving a small garrison under a trusted lieutenant, Pedro Alvorado, to maintain control in Tenochtitlan.

Returning to the coast with 400 men, Cortes began sending emissaries to seduce many of Narvaez's captains, liberally using the gold he'd obtained from the Mexica. When the two armies camped near each other, Cortes even entertained some of these captains, deploying his personal charm. Many were receptive being more interested in acquiring wealth themselves than in a police action against a renegade conquistador doing much the same as they would in the same position.

Having weakened by subversion the position of the overconfident Narvaez, on May 28 Cortes launched a night assault on his camp. With many of Narvaez's men defecting the fight was sharp and short with Cortes capturing the wounded Narvaez, who (no surprise) eventually became an admirer of Cortes.

Incorporating Narvaez's men into his force, Cortes returned to Tenochtitlan with 1,000 men but found the city he returned to on June 24 was much different than the city he'd left two months earlier. Alvorado had none of the subtlety of Cortes. When Cortes left, the Mexica in the capital thought it was the last they would see of him. Tensions grew in the city and Alvorado heard rumors of a planned uprising and massacre of his garrison.

On May 16, in the midst of an important Mexica festival celebration that attracted many of the leading nobles, Alvorado blocked the exits to the square and launched a slaughter, killing thousands, including senior lords of the Mexica. This ignited a violent reaction from the Mexica who launched an attack on Alvorado and his men that might have succeeded but for Moctezuma, under threat from Alvorado, pleading for the attackers to stop. They did, but from that moment on respect was gone for Moctezuma. When Cortes arrived, Alvorado had been besieged within the city for a month. Cortes made one last attempt to use Moctezuma to restore peace but the emperor was stoned and killed by his own people. Cortes knew he had to leave the city or be trapped and die within it. What must he have thoughts about the lost opportunity - a fabulously wealthy kingdom that he had peaceably conquered, now a potential deathtrap.

On the night of June 30 the Spaniards and their Indian allies attempted to escape. In an event that became known as La Noche Triste (The Night of Sadness) several hundred Spaniards, thousands of Indian allies and most of their treasure was lost on the causeways. Cortes narrowly escaped death, and after a harrowing journey, in which his leadership kept his men together while under constant attack, they reached Tlaxcala, where the natives decided to keep their pact with the Castilians, though by that time the 400 remaining conquistadors were all wounded and exhausted.

And now starts another remarkable chapter in the conquest. Cortes and his men began gathering their strength. The Tlaxcalans and other Indian allies began to congregate and hundreds of more Spanish conquistadors from the Caribbean arrived, attracted by the tales of the wealth found by Cortes.

In the meantime it turned out the something else had arrived with the Narvaez expedition.

April 1520: Smallpox arrives on the American mainland.

Early 1519 saw the first large-scale outbreak of smallpox in the New World. Reaching Hispaniola via ship from Spain it quickly exploded on an island where the natives had no resistance to the disease. By the end of the year the local Indians were almost all dead. In November it reached Cuba where the native population collapsed. By the time Narvaez left on his expedition the following February some of the men with him carried the infection. They stopped briefly in the Yucatan touching off an epidemic that killed the royal family. In Veracruz, the tribal allies on the coast were affected and decimated.

And then, in September, smallpox reached the Valley of Mexico where it raged into November causing a massive number of deaths including that Moctezuma's successor. The harvest in the valley was ruined as maize was not collected because of a shortage of hands. The nobility was largely destroyed. Cortes' position became stronger because the natives saw the Spaniards were mostly immune to the disease. As positions became open among the nobility in allied towns, Cortes was asked to name the successors further strengthening his hold over those not directly ruled by the Mexica.

It is impossible to know the complete toll but surviving writings of the Mexica refer to the devastation the epidemic caused.

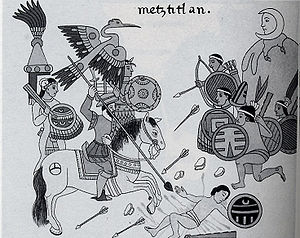

(Spanish & Mexica combat from History of Tlaxcala; source Wikipedia)

(Spanish & Mexica combat from History of Tlaxcala; source Wikipedia)At the end of 1520, Cortes with his rejuvenated conquistadors, along with tens of thousands of Indian allies, re-entered the Valley of Mexico, seizing the shore towns of Mexica allies, laying siege to Tenochtitlan and then, in mid-June beginning a direct assault across the causeways to the city. Desperate to preserve the city and its wealth, Cortes tried several times to negotiate with the Mexica but all attempts were refused. With a decimated leadership and population, starving and surrounded by their Spanish and Indian enemies, the Mexica fought bravely and with incredible determination against overwhelming odds and it was not until August 13, 1521 that it was all over, leaving Cortes in possession of a ruined city.(Emperor Cuauhtemoc surrenders to Cortes from brittanica)

In the aftermath, many of the surviving Mexica nobility intermarried with the Castilians, who were rewarded with large landholdings and laborers tied to that land. Some Mexica, like one of Moctezuma's daughters, became large landholders in their own right, and many of the other surviving children of the rulers in the Valley of Mexico did well, with one branch becoming the Counts of Moctezuma and surviving for many generations in Spain. But for most of the populace it was simply trading one master for another along with the disruption of their cultures and traditions.

Cortes named his son with his Mayan interpreter Marina, Martin in honor of his father. Marina later married one of the conquistadors. Martin, along with the other bastard children of Cortes, was legitimised by Pope Clement VII. After many years in Mexico, Cortes returned to Spain in the 1540s, dying there in 1547. Martin Cortes inherited part of his large estate.

What was the significance of all this?

From a demographic perspective it was devastating for the inhabitants of Mexico. The initial smallpox epidemic was followed by measles and other diseases to which the natives had no resistance. The first census of Mexico was conducted in the 1560s, almost half a century after the conquest, and counted 2.6 million inhabitants. The scholarship around the population of Mexico pre-conquest is still hotly argued and widely varying estimates but most are within the range of 8-10 million, so we see a 75% reduction over those first few decades (and the population continued to decline into the 17th century from further epidemics). These epidemics fatally weakened the ability of the Indians of the Western Hemisphere, including the Incas of Peru who were ravaged by disease prior to Pizarro's arrival, to resist European conquerors and settlers. As one example, further north disease brought by English and French fishermen to the coasts of New England at the beginning of the 17th century may have killed up to 90% of the local population leaving much open land and few natives when the Pilgrims and then Puritans landed a couple of decades later.

At first Cortes attempted to rebuild Tenochtitlan but eventually the lake on which it stood was drained and Mexico City rose atop the lake bed and ruined city, the result a city particularly susceptible to earthquakes because of its unsteady footing. The Spanish also began importing African slaves, further changing the demographic landscape [the first large importation of African slaves into the Americas falls just outside this ten year time frame but will be touched on in Part 3 of this series].

The wealth and sophistication of Mexico was eye opening for the Castilians. The amounts were staggering. In twelve years, from 1509 through 1521, the conqueror and ruler of Puerto Rico, Ponce de Leon, was able to extract 22,000 pesos from the island. In his first three months in Tenochtilan, Cortes assembled a personal fortune worth officially 160,000 pesos and unofficially perhaps as much as 700,000 pesos.

But what that wealth inspired was even more important for the long term. The tales of wealth and the glory of Cortes' conquest attracted even more adventurers from Spain to the New World. Further conquests quickly followed to the south in the Yucatan and Central America while conquistadors constantly searched for another Mexico. A decade later, Francisco Pizarro, a distant relative of Cortes, began an expedition that would bring treasure in an amount dwarfing that of Mexico - the conquest of the Inca Empire and most importantly of all, the discovery during the 1540s of the Silver Mountain of Potosi in what is now Bolivia. In the later part of the 16th century, Potosi (elevation 13,420 feet) was the largest city in the Western Hemisphere with over 100,000 inhabitants. Its silver flowed across the Atlantic to fill the coffers of the Spanish Hapsburgs as they engaged in war across Europe, funding the Armada against England in 1588, triggering massive inflation across the continent and ultimately leading to the decline of an overextended Spain.

The conquest of Mexico also made New Spain a center for global trade. On September 20, 1519, as Cortes was entering Tlaxcala, Ferdinand Magellan set forth from Spain with five ships in an attempt to sail around the world. In April 1521, as Cortes was fighting his way back to Tenochtitlan, Magellan was killed in an encounter with natives in the Philippines. Finally, on September 6, 1522 one ship with eighteen starving and ragged crewman (of an original 237) staggered into a Spanish harbor.

Subsequent Spanish voyagers discovered trade routes from the Pacific Coast of Mexico to Manila in the Philippines and from there opened up trade with China, in which ships with silver from America would sail to Manila once a year, and be exchanged for silk, porcelain and other valuable Chinese goods. After offloading at Acapulco, the Chinese goods would be transshipped to the Gulf coast and then sent on to Spain and the rest of Europe.

Along with goods, the route also became used by people, leading Charles C Mann, in his book 1493, to call the Mexico City of the late 16th century and 17th century the first true global city. Chinese, Japanese, and Southeast Asians ended up in Mexico, and Mann claims the first Chinatown in the Americas was in Mexico City, centered around an Asian marketplace built upon atop the old city center of Tenochtitlan. Samurai protected the trade caravans as they moved from Acapulco to Mexico City. The ceramics industry started in Puebla, Mexico, probably employing Chinese workers who brought their designs along with them.

The standard 17th century text on China for Europeans, published in editions in many languages, was a History of the Most Notable Things, Rituals and Customs of the Great Kingdom of China composed by Juan Gonzalez de Mendoza, a Dominican in Mexico City, who describes an Easter Parade in the city:

"a company of soldiers . . . on horseback, and was preceded by mournful horn-players. When the procession came to the royal palace, the Chinese and the [Franciscans] fought to be at the head of the line; they beat each other over the shoulders with clubs, and with their Crosses; and many were wounded."We'll close with these words from 1493:

. . . Mexico City's multitude of poorly defined ethnic groups from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas made it the world's first truly global city . . . it was the place where East met West under an African and Indian gaze. Its inhabitants were ashamed of the genetic mix even as they were proud of their cosmopolitan culture, perhaps none more so than the poet Bernard de Balbuena, whose Grandeza Mexicana is a two hundred page love letter to his adopted home. "In thee," he wrote addressing Mexico City,

Spain is joined with China

Italy with Japan, and finally

an entire world in trade and order.

In thee, enjoy the best of the treasures

of the West; in thee, the cream

of all luster created in the East.

Coming Soon - Part 2 in which Martin & Anne cause havoc in Europe.

No comments:

Post a Comment