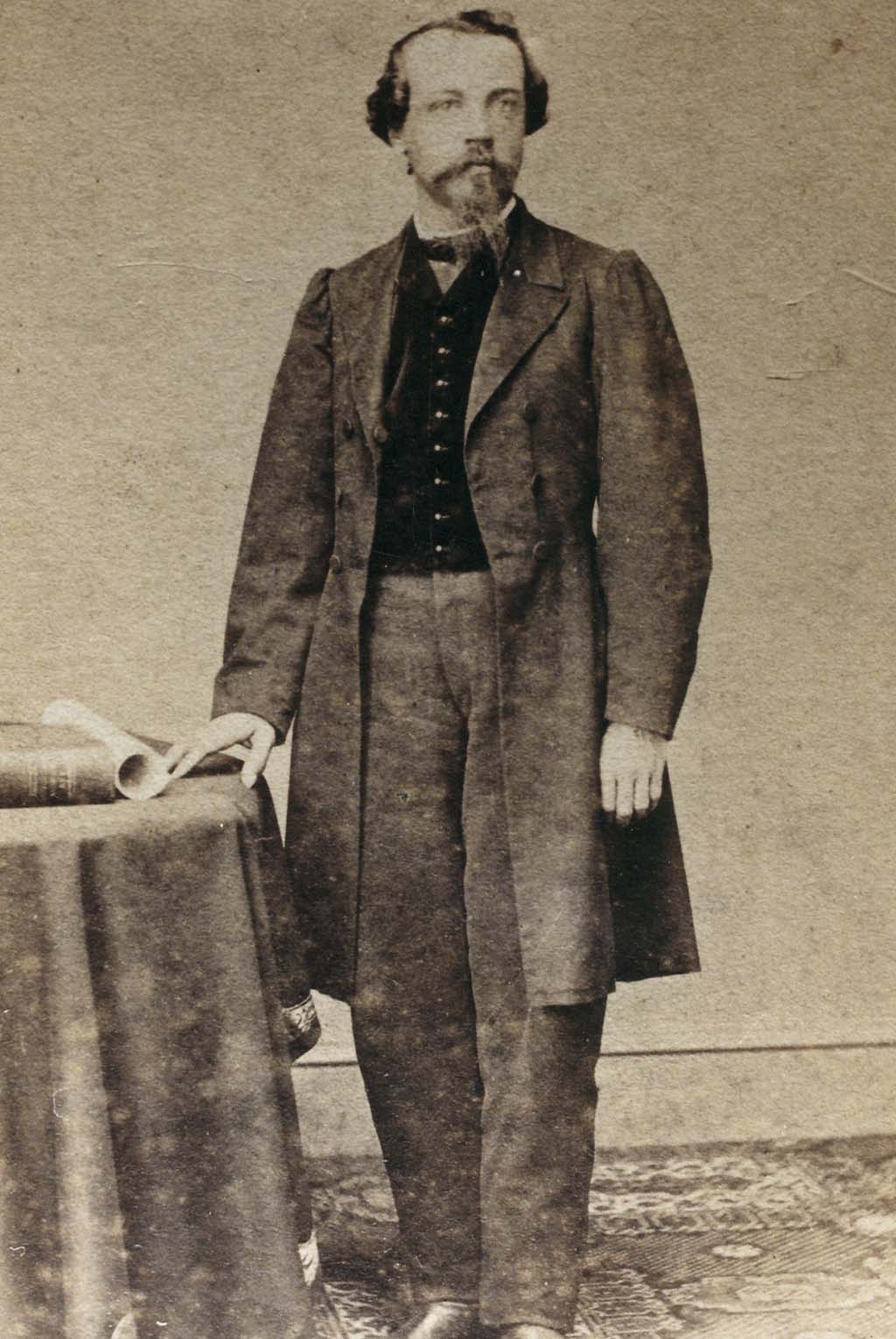

(Arnold Bertonneau)

(Arnold Bertonneau)

On the afternoon of March 3, 1864, two Creole mixed-race Louisianians from New Orleans, Jean Baptiste Roudanez and E Arnold Bertonneau, entered the White House to meet with President Abraham Lincoln. Their purpose was to present a petition seeking enfranchisement of "all the citizens of Louisiana of African descent, born free before the rebellion". Both the 46 year old Roudanez and 27 year old Bertonneau had French fathers and African mothers.

Thirteen years later, Bertonneau filed the first federal lawsuit seeking desegregation of public schools (Bertonneau v School District). The circuit court's ruling dismissing the case was later cited by the Supreme Court in support of its decision in Plessy v Ferguson (1896).

In 1912 when Bertonneau, then living in California, died, his death certificate listed him as white. (1)

Bertonneau's life encapsulates the tortured nature of how race was handled in his lifetime, and the crushing disappointment of his hopes, and those of the black population, during the post Civil War era.

Bertonneau came to my attention because he appears in two books I've recently read; A House Built By Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House by Jonathan W White, and The Black Man's President: Abraham Lincoln, African Americans, & the Pursuit of Racial Equality by Michael Burlingame (2). Both authors are noted scholars of the era; White is a professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University, while Burlingame is Chair in Lincoln Studies at the University of Illinois.

The topic of both books is Lincoln's relationships with African Americans, with a focus on the White House years, though Burlingame spends more time on Lincoln's experiences in Illinois where he had free black neighbors. While I knew about some of these events, such as Lincoln's three meetings with Frederick Douglass, and his controversial August 1862 meeting with black ministers about colonization, the sheer number and variety of encounters between the president and blacks during his time in the White House was surprising to me.(3) It truly was revolutionary, a revolution ended in the wreckage of Reconstruction.

Prior to Lincoln, we know of only two occasions when black Americans were invited to the White House. The first, in 1812, was when James Madison and Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, met with Paul Cuffe, a wealthy black merchant, ship builder, and fascinating figure in his own right, at which Cuffe successfully appealed to the president to overrule a customs decision to seize cargo on one of his vessels. The second, John Tyler's invitation to minister Daniel Payne to preside at a funeral for the president's body servant. Twenty years later, Payne had the opportunity to meet with Lincoln, later writing that he:

"was a perfect contrast with President Tyler . . . President Lincoln received and conversed with me as though I had been one of his intimate acquaintances or one of his friendly neighbors".

There was also one other noteworthy interaction with an American president, though it took place in Philadelphia, the year before the White House was completed. In 1799, a black diplomat from Santo Domingo dined with John Adams and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering.

One of my favorite incidents, occurred on July 4, 1864. In late June a delegation of black Catholics met with Lincoln. Barred from the sanctuary of the Catholic church in the city, and their children barred from public school, they sought to raise funds for a chapel and school, for which they sought the President's approval to use the White House grounds for a fund-raising picnic. Lincoln granted their request, apparently the first time any group had used the White House grounds for private fund-raising. The picnic was a great success, in attendance and financially, and a month later a black Baptist church held a similar event at the White House. These events triggered horrified reactions in the Democratic press.

Reading about Lincoln over the years, I've become more aware of his flaws and his mistakes. Yet, even with that, my appreciation for his greatness and humanity has only grown, as well as my appreciation for how good a politician he was.

While the books shed much light on Lincoln, they also reveal the world of free blacks as it existed in mid-19th century America, what they thought about Lincoln at the time, and the conditions and limits under which they had to navigate within white America. Learning about their stories was what led me to do more reading on E Arnold Bertonneau.

Bertonneau and Roudanez sprang from a unique American community, the Creoles of southern Louisiana and, more specifically, the Creoles of Color. Creoles were the descendants of French settlers prior to the American acquisition in 1803, as well as the French and mulattoes fleeing the turmoil in Santo Domingo and the Haitian Revolution in the early 1800s. Within the category of Creoles were a significant number of mixed race persons who, in contrast to the rest of the country, were free, educated, and played a role in the general society of New Orleans. In fact, many of these Creoles played a prominent role in the region, often large property owners, merchants, and sometimes owning slaves. By the beginning of the Civil War there were 11,000 free blacks in Louisiana (predominantly Creole) and, in order to maintain their position in an increasingly race-conscious South, where the prior three decades had seen increasing restrictions not just on slaves, but also on free blacks, they emphasized their difference from other Africans. Burlingame quotes an 1864 article in the New Orleans Tribune, the paper of the Creoles of color, to the effect:

". . . while we are of the same race as the unfortunate sons of Africa who have trembled until now under the bondage of a cruel and brutalizing slavery, one cannot, without being unfair, confuse the newly freed people with our intelligent population which, by its industry and education, has become as useful to society and the country as any other class of citizens."

This was also reflected in the views of whites. In 1859, the New Orleans Picayune observed in an editorial:

"Our free colored population form a distinct class from those elsewhere in the United States. Far from being antipathetic to the whites, they have followed in their footsteps, and progressed with them, with a commendable spirit of emulation, in the various branches of industry most adapted to their sphere. Some of our best mechanics and artisans are to be found among the free colored men. They form the great majority of our regular, settled masons, bricklayers, builders, carpenters, tailors, shoemakers . . . whilst we count among them in no small numbers, excellent musicians, jewelers, goldsmiths, tradesmen and merchants."

When the war began, almost 800 free blacks in New Orleans volunteered for the Native Guards, including Bertonneau who was appointed captain, forming a regiment to protect the city from federal forces. Bertonneau later wrote of this action, "Without arms and ammunition, or any means of self-defense, the condition and position of our people were extremely paralyzed; could we have adopted a better policy?". Colored Creoles had been members of the Louisiana militia in the past, with several hundred fighting in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, of whom twenty eight survivors were signatories to the petition presented to Lincoln in March 1864.

At the time, Bertonneau, then 24 and very light skinned with blue eyes, was already a prominent member of the Creole community, a prosperous wine merchant, member of La Societe d'Economic d'Assistance Mutuelle, and supporter of La Societe Catholique pour L'Institution des Orphelins dan L'Indigence (known also as the Couvent School, the first community school dedicated to education of black children in the Deep South).

Although Confederate authorities allowed the Native Guards to drill, they were not provided with arms or uniforms and so did not participate in the defense of New Orleans when the Federals successfully attacked in April 1862. After the city's capture Union general, Benjamin Butler, urged the Native Guards to join the Union Army, which many did, along with escaped slaves, eventually forming three regiments. Bertonneau was among these, being reappointed as a captain.

In early 1863, after General Nathaniel Banks replaced Butler, Banks decided to weed out black officers and Bertonneau resigned in protest stating:

"When I joined the Army I thought that I was fighting for the same cause, wishing only the success of my country would suffice to alter a prejudice which had existed. But I regret to say that five months experience has proved the contrary."

In mid-summer 1863, when a Confederate attack on New Orleans seemed possible, Bertonneau reenlisted for a sixty day stint.

In the latter part of 1863 President Lincoln began putting pressure on Generals Banks and Shepley (the military governor of Louisiana) to hold elections for civilian officials and to convene a constitutional convention, in order to begin the process of bringing the state back into the Union. Shepley responded by calling for elections and enfranchising white Union soldiers. The colored Creole community sent petitions to Shepley and Banks asking for the right to vote, but neither responded. It was decided to appeal directly to President Lincoln.

In January 1864, Roudanez and Bertonneau drafted the petition requesting enfranchisement for all of African descent, born free before the Civil War. The petition was eventually signed by about 1,000 free blacks.

Accompanied by Pennsylvania Congressman William D Kelly, one of the founders of the Republican Party, the two met with the President on March 3, and presented their petition. (4) The meeting is described by all sources as cordial.

Author White summarizes Lincoln's reaction at the March 3 meeting:

If giving black men the right to vote became "necessary to close the war, he would not hesitate," he said, for he saw "no reason why intelligent black men should not vote". But black suffrage was "not a military question" and he believed it had to be handled by the constitutional convention in Louisiana. As president, Lincoln said that he "did nothing in matters of this kind upon moral grounds, but solely upon political necessities." Since the petition based its claim "solely on moral grounds" it "did not furnish him with any inducement to accede to their wishes."

According to one observer of the meeting, Lincoln said "I regret, gentlemen, that you are not able to secure all your rights, and that circumstances will not permit the government to confer them upon you".

The president then went out to suggest that the petition be amended, and then sat down with his visitors to write out the suggested modifications, shocking some of the white observers in the room.

It is not known what changes the president suggested, but Roudanez and Bertonneau rewrote the petition over the next few days to include poor, uneducated, and newly freed blacks and it was resubmitted to Lincoln. Ultimately, the change was not just tactical, as we can follow Bertonneau's own thinking and the realization that the fate of the free Creoles of color and those of the newly freed former slaves were linked.

The meeting apparently encouraged Lincoln to take an additional step. On March 13, 1864 he wrote a letter congratulating Michael Hahn, who had just been elected governor of Louisiana. It was brief, but pointed:

I congratulate you on having fixed your name in history as the first-free-state Governor of Louisiana. Now you are about to have a Convention which, among other things, will probably define the elective franchise. I barely suggest for your private consideration, whether some of the colored people may not be let in---as, for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks. They would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom. But this is only a suggestion, not to the public, but to you alone.Yours trulyA. LINCOLN

when negro suffrage was a thing to speak of in bated breath, and with many of shudder. Even then, in advance of almost every leading man of the party which supported him, Mr Lincoln was found inquiring - in a quarter where he knew inquiry to be almost equal to command.

We ask that, in the reconstruction of the state government there, the right to vote shall not depend on the color of the citizen; that the colored citizen shall have and enjoy every civil, political and religious right that white citizens enjoy; in a word, that every man shall stand equal before the law. To secure these rights, which belong to every free citizen, we ask the aid and influence of every true loyal man all over the country. Slavery, the curse of our country, cannot exist in Louisiana again.In order to make our state blossom and bloom as the rose, the character of the whole people must be changed. As slavery is abolished, with it must vanish every vestige of oppression. The right to vote must be secured; the doors of our public schools must be opened, that our children, side by side, may study from the same books, and imbibe the same principles and precepts from the Book of Books, learn the great truth that God “created of one blood all nations of men to dwell on all the face of the earth”; so will caste, founded on prejudice against color, disappear.

You can read the entire speech here.

Bertonneau continued to play a role in lobbying for equal treatment, joining protests in 1866 of President Johnson's reconstruction plan allowing readmission of states without enfranchisement of blacks. He was at the 1866 constitutional convention in New Orleans, as part of a group urging black suffrage, when it was attacked by a white mob which killed more than 30 blacks.

That attack and other violent incidents in the South, led Congress to impose a harder path towards reconstruction which resulted in another constitutional convention at which blacks, including Bertonneau, were delegates, and led to provisions allowing blacks to vote. Bertonneau also helped establish integrated Masonic lodges in the state.

In the 1870s, Bertonneau held a position at the Customs House in New Orleans but the gains of the late 1860s were already starting to erode as Northern support for reconstruction began to fade.

In 1877 the Orleans Parish school board decided to resegregate New Orleans schools. Bertonneau, by now the father of four children, filed his lawsuit in Federal District Court (you can find the case file here and the circuit court decision here) though two prior suits in state court had already failed. As recounted above, his suit also failed.

Bertonneau's first wife died in 1888. He remarried in 1891, had three more children, and opened a dry cleaning business (this photo shows Bertonneau, on the left, and two of his sons at his cleaning establishment). His once active community involvement declined, perhaps because times for blacks were becoming much grimmer as Jim Crow took hold. The 1896 case, Plessy v Ferguson, had its origin in the efforts of the black community in New Orleans to stem the tide of exclusion and repression. Two years later the Louisiana legislature effectively disenfranchised most black voters, and two years after that riots in New Orleans destroyed many black businesses. These events prompted many colored Creole families to leave.

In 1902, Bertonneau and his family joined the exodus, moving to California, where he died in Los Angeles in 1912. His eldest son, Arnold John Bertonneau went on to a very successful business career in southern California, in the grocery and hotel business and becoming an organizer of a bank in Pasadena.

-----------------------------

(1) Bertonneau is not unique in changing race. Homer Plessy, the litigant in the famous 1896 Supreme Court case, was 7/8 white, but considered black in Louisiana. In the 1910 census he is listed as black, but in 1920 is shown as white.

(2) The title of Burlingame's book is taken from Frederick Douglass' speech on June 1, 1865 at Cooper Union in New York City, where he proclaimed Lincoln as:

"emphatically the black man's President, the first to show any respect for the rights of a black man, or to acknowledge that he had any rights the white man ought to respect"

Burlingame also points out that in December 1864, a Democratic opposition newspaper also called Lincoln "emphatically the black man's president" along with being "the white man's curse".

At different times, Douglass gave different perspectives on Lincoln. In 1876, at the dedication of the Freedman's Monument, he called Lincoln "preeminently the white man's President". Douglass was quite astute in tailoring his messages for his audience. The 1865 speech was given to a black audience, while the 1876 talk was to a mixed audience, but with a message clearly designed for whites, including President Grant who was in attendance. For more on the Freedman Monument speech you can read my 2016 post linked here.

(3) One of those who met the president was Robert Smalls, a young man who escaped slavery by seizing a Confederate warship in Charleston Harbor and sailing it out to the blockading Union fleet. Smalls eventually became the first black commander in the Union navy and, after the war, served five terms in Congress as a South Carolina representative. His incredible saga is told in Be Free or Die by Cate Lineberry.

(4) To my frustration, I've been unable to locate a full text of the petition.

(5) Reid later become editor of the New York Tribune after the death of Horace Greeley. A Republican, he was later appointed ambassador to Britain and France and was the party's vice-presidential nominee in 1892.

(6) The prior year, Attorney General Bates issued an official opinion "that the free man of color, if born in the United States, is a citizen of the United States", repudiating the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision of 1857.

No comments:

Post a Comment