On December 18, 1799, a private funeral was held at Mt Vernon for George Washington who died four days earlier, at age 67, two and a half years after leaving the Presidency. It was to be followed by the new nation's first national funeral at Philadelphia (seat of federal government before the District of Columbia) on December 26, 1799.

(Funeral procession Philadelphia, December 1799)

Washington remains a towering, but personally remote, figure, at least partly by his own design. Unlike Benjamin Franklin or the voluble John Adams, Washington seems as a man always in control of himself, though in reality, he had an explosive, but rarely triggered, temper (for an occasion when an enraged Washington used "very singular expressions", read this account). Nor was he a great political philosopher like Madison or Jefferson and, always conscious of how he was viewed by his fellow citizens, he allowed us only brief glimpses of his inner life.

The ex-President's final will and testament, a document prepared and written by him, is dated July 9, 1799. Below are some of the interesting excerpts with some background (you can fine the entire text here)

In the name of God amen I George Washington of Mount Vernon—a citizen of the United States, and lately Pr⟨es⟩ident of the same, do make, ordai⟨n⟩ and declare this Instrument; w⟨hic⟩h is written with my own hand ⟨an⟩d every page thereof subscribed ⟨wit⟩h my name, to be my last Will & ⟨Tes⟩tament, revoking all others."In the name of God amen" was a common opening phrase in wills, though its popularity sharply declined during the 20th century. It was used by figures as disparate as William Shakespeare (d.1616) and "Shoeless" Joe Jackson (d.1951), according to In the Name of God, Amen: Language in Last Wills and Testaments, by Karen J Sneddon, Quinnipiac Law Review, Vol. 29:665 (2011), as well as in the opening of the Mayflower Compact of November 1620, entered into by the ship's passengers, just before landing at Plymouth, and considered the first document of popular government in the Americas, which includes this language:

. . . do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony . . .

"a citizen of the United States, and lately President of the same"I searched online for the last wills and testaments of the next six Presidents and was able to find those of Jefferson (d.1826), Madison (d.1836) and Jackson (d.1845). None include these phrases, nor anything close to them. Jefferson and Jackson make no reference to their role in the National Government and Madison's is limited to a request that his Report on the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention be published:

Considering the peculiarity and magnitude of the occasion which produced the Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, the Characters who composed it, the Constitution which resulted from their deliberations, its effects during a trial of so many years on the prosperity of the people living under it, and the interest it has inspired among the friends of free Government,Madison provided that any profits from such publication were to go to his wife, Dolly, but only after the first $2000 went to the American Colonization Society, an organization founded by abolitionists to provide free transport for free African-Americans to return to Africa. These returnees founded the country of Liberia.

Inserting "a citizen of the United States, and lately President of same", as the only descriptors for himself, was a deliberate public statement by Washington of what he felt most important for posterity. He was not, unlike Jefferson, first and foremost a citizen of Virginia, rather he was a citizen of the United States. As a strong Federalist and advocate for a stronger central government to replace the weak Articles of Confederation (he was a forceful presence behind the scenes in the political maneuvering leading to the Constitutional Convention), the preservation of the Union was his overriding concern, and the symbolism of those words in his will reinforced the sentiment expressed in his Farewell Address (1796)

The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize.

"⟨I⟩tem. To my dearl⟨y be⟩loved wife Martha Washington ⟨I⟩ give and bequeath the use, profit ⟨an⟩d benefit of my whole Estate, real and p⟨er⟩sonal, for the term of her natural li⟨fe⟩—except such parts thereof as are sp⟨e⟩cifically disposed of hereafter:"Washington married Martha Custis, a wealthy widow, in 1759. They had no children, but raised the two surviving children from Martha's marriage to Daniel Parke Custis as their own. When 24 year old John Parke Custis, died of camp fever at Yorktown in 1781, while serving as an aide to his step-father, they also raised two of his children, one of whom, George Washington Parke Custis, had a daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis. In 1831, Mary Custis married a young lieutenant in the U.S. Army, Robert E Lee. It was through the Custis marriage that Lee became master of the great mansion that is now part of Arlington Cemetery, property confiscated by the Federal government during the Civil War after Lee joined the Confederate cause, after declining an offer to command the Federal forces. Martha died in May 1802.

⟨Ite⟩m Upon the decease ⟨of⟩ my wife, it is my Will & desire th⟨at⟩ all the Slaves which I hold in ⟨my⟩ own right, shall receive their free⟨dom⟩The longest section of the will concerns the disposition of slaves, a tangled story reflecting the laws and customs of the time. Before the Revolution, Washington seems to have not examined the moral aspects of slavery, though he had expressed sentiments in the 1760s about its economic inefficiency. His attitude began to change during the war. In part, because of his exposure to free black American soldiers, in part because of the prompting of two of his young aides, John Laurens and Marquis de Lafayette. Laurens was an impassioned opponent of slavery (see the Forgotten Americans post) who, in turn, inflamed Lafayette on the same topic. Both never hesitated to raise the issue with General Washington.

(Washington and Lafayette at Mt Vernon, 1784)

By 1779, Washington told Lund Washington, manager of Mt Vernon, of his desire to abandon slave labor when the war ended. Though that did not happen, Washington continued to seek a solution. During Lafayette's visits in 1784 and 1785 they held lengthy discussions about slavery, and by 1786 he supported a proposal in the Virginia legislature for gradual emancipation, in September of that year writing John Francis Mercer, who owed him money, that he would not accept payment in slaves:

I never mean (unless some particular circumstances should compel me to it) to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure & imperceptible degrees.Washington's evolving views contained an element of moral recognition, as well as his sensitivity of how future generations would judge his actions, combined with an acute appreciation of the economic impacts of any type of emancipation that served to temper his sense of urgency.

In 1790 he showed that, as a matter of national policy, his priority was preservation of the new Union, over action to abolish slavery, when he supported James Madison in deferring action on an emancipation proposal in the first session of the U.S. Congress, because of his fear that the issue could lead to dissolution of the country.

Nonetheless, he continued to seek a solution to his personal situation at Mt Vernon, as described in detail in Joseph Ellis' splendid short biography, His Excellency: George Washington. As an operating concern, Mt Vernon did not make money. Washington refused to sell or break up slave families and, as a result, he had an aging population of enslaved that was increasingly unproductive.

To emancipate them during ⟨her⟩ life, would, tho’ earnestly wish⟨ed by⟩ me, be attended with such insu⟨pera⟩ble difficulties on account of thei⟨r interm⟩ixture by Marriages with the ⟨dow⟩er Negroes, as to excite the most pa⟨in⟩ful sensations, if not disagreeabl⟨e c⟩onsequences from the latter, while ⟨both⟩ descriptions are in the occupancy ⟨of⟩ the same Proprietor; it not being ⟨in⟩ my power, under the tenure by which ⟨th⟩e Dower Negroes are held, to man⟨umi⟩t them.In this passage, Washington begins to explain the reasons for his decisions to contemporaries and posterity. At the time of his death there were 317 slaves at Mt Vernon. Washington owned 124 and leased 40 others. The remainder were part of the dower of Martha Washington from her first husband, and would revert to her son upon her death. The only slaves that George could legally emancipate were those he owned. And while there is no direct evidence, Ellis convincingly speculates, based on what we know, that Martha Washington did not share her husband's views on the desirability of ending slavery. It also references the reality of extensive intermarriage between George and Martha's slaves, potentially created a situation where one would be free and the other enslaved.

And whereas among ⟨thos⟩e who will recieve freedom ac⟨cor⟩ding to this devise, there may b⟨e so⟩me, who from old age or bodily infi⟨rm⟩ities, and others who on account of ⟨the⟩ir infancy, that will be unable to ⟨su⟩pport themselves; it is m⟨y Will and de⟩sire that all who ⟨come under the first⟩ & second descrip⟨tion shall be comfor⟩tably cloathed & ⟨fed by my heirs while⟩ they live; and that such of the latter description as have no parents living, or if living are unable, or unwilling to provide for them, shall be bound by the Court until they shall arrive at the ag⟨e⟩ of twenty five years;The first provision regarding support of old and infirm freed slaves, was a requirement of Virginia law. The latter part goes to Washington's desire to ensure support.

The Negros thus bound, are (by their Masters or Mistresses) to be taught to read & write; and to be brought up to some useful occupation, agreeably to the Laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, providing for the support of Orphan and other poor Children, and I do hereby expressly forbid the Sale, or transportation out of the said Commonwealth, of any Slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever.Here Washington sought to ensure the freed slaves be provided with the ability to support themselves. The latter part continues his practice, while living, of not selling any slaves or breaking up families.

And I do moreover most pointedly, and most solemnly enjoin it upon my Executors hereafter named, or the Survivors of them, to see that th⟨is cla⟩use respecting Slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled at the Epoch at which it is directed to take place; without evasion, neglect or delay, after the Crops which may then be on the ground are harvested, particularly as it respects the aged and infirm; seeing that a regular and permanent fund be established for their support so long as there are subjects requiring it; not trusting to the ⟨u⟩ncertain provision to be made by individuals.This section can be read as both an attempt to make the public understand the seriousness of his undertakings regarding his slaves as well as further emphasizing to his Executors, who may not have shared his views on slavery, about the need to adhere to these provisions. The evidence is that the Executors abide by terms of the will, and according to their accounts, by 1833, more than $10,000 had been provided in pensions to former slaves living at, or near, Mt Vernon.

On January 1, 1801, seventeen months prior to her death, Martha Washington freed her husband's slaves. This was done in advance of her death upon the advice of her nephew, Bushrod Washington, because news of her husband's direction to free his slaves upon her death, created anticipation and impatience among the slaves and it was felt better to move more quickly towards emancipation.

And to my Mulatto man William (calling himself William Lee) I give immediate freedom; or if he should prefer it (on account of the accidents which ha⟨v⟩e befallen him, and which have rendered him incapable of walking or of any active employment) to remain in the situation he now is, it shall be optional in him to do so: In either case however, I allow him an annuity of thirty dollars during his natural life, whic⟨h⟩ shall be independent of the victuals and cloaths he has been accustomed to receive, if he chuses the last alternative; but in full, with his freedom, if he prefers the first; & this I give him as a test⟨im⟩ony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.William Lee was purchased by Washington in 1767. Interestingly, until the Revolution all of Washington's references call him "Billy", but after that time he is called "Will" or "William". Lee remained at Washington's side throughout the Revolution and also attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787. By this time, Lee was crippled from leg injuries. He continued to live at Mt Vernon before dying in 1810.

The balance due to me from the Estate of Bartholomew Dandridge deceased (my wife’s brother) and which amounted on the first day of October 1795 to four hundred and twenty five pounds (as will appear by an account rendered by his deceased son John Dandridge, who was the acting Exr of his fathers Will) I release & acquit from the payment thereof. And the Negros, then thirty three in number) formerly belonging to the said estate, who were taken in execution—sold—and purchased in on my account in the year [ ] and ever since have remained in the possession, and to the use of Mary, Widow of the said Bartholomew Dandridge, with their increase, it is my Will & desire shall continue, & be in her possession, without paying hire, or making compensation for the same for the time past or to come, during her natural life; at the expiration of which, I direct that all of them who are forty years old & upwards, shall receive their freedom; all under that age and above sixteen, shall serve seven years and no longer; and all under sixteen years, shall serve until they are twenty five years of age, and then be free.This provision relates to a complicated family history. After Martha Custis' first husband died and before marrying George, she made a large loan to her brother Bartholomew Dandridge, secured by a bond for the debt. In 1773, George ended up holding the bond, and when Dandridge died in 1785, the loan, and accumulated interest, remained unpaid. In 1788, Dandridge's son persuaded Washington to seek title to Dandridge's slave in partial payment of the debt and to forestall other creditors who would force their sale. Washington obtained title, but left the slaves in the possession of Bartholomew's widow. The provision in the will provides for their eventual emancipation after her death.

Item To my Nephew Bushrod Washington, I give and bequeath all the Papers in my possession, which relate to my Civel and Military Administration of the affairs of this Country; I leave to him also, such of my private Papers as are worth preserving;13 and at the decease of wife, and before—if she is not inclined to retain them, I give and bequeath my library of Books and Pamphlets of every kind.Bushrod Washington (b.1762) was the son of George's brother John. The year prior to Washington's death he was appointed an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, a position he held until his death in 1829. Bushrod was a founder and first President of the American Colonization Society to which James Madison made a bequest in his will. Abolitionists criticized Bushrod because, despite his role with the Society, he sold many of his own slaves to raise fund to support Mt Vernon, rather than free them.

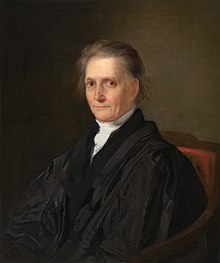

(Bushrod Washington)

(Bushrod Washington)George Washington took great care to preserve his papers (though Martha burned all letters between the two of them before her death). These included 28 volumes of Revolutionary War documents, hundreds of private letters and his presidential papers (other than those he had designated be provided to John Adams, his presidential successor). The papers remained the possession of the Washington family until Bushrod's nephew, George Corbin Washington sold the public papers to the United States in 1834 for $25,000 and the private papers in 1849 for $20,000. They now reside in the Library of Congress. GC Washington served four terms as a member of the U.S. Congress from Maryland.

Item To my brother Charles Washington I give & bequeath the gold headed Cane left me by Doctr Franklin in his Will.A year before his death in 1790, Benjamin Franklin added a codicil to his will, bequeathing his treasured gold-headed walking stick to George Washington; "My fine crab-tree walking-stick, with a gold head curiously wrought in the form of the cap of liberty, I give to my friend, and the friend of mankind, General Washington. If it were a Sceptre, he has merited it, and would become it. . " The walking stick had been a gift from an admirer during Franklin's stint as Ambassador to France. For some more background on the item, watch this video:.

Charles Washington predeceased his brother, dying in September 1799. The walking stick has been in possession of the United States since 1845 and is currently on display at the National Museum of American History.

To General de la Fayette I give a pair of finely wrought steel Pistols, taken from the enemy in the Revolutionary War.There is some confusion about these Pistols. The inventory of Washington's estate included four pairs of pistols and it is unclear which pair, and the provenance, of was gifted to the Marquis. You can read more of the close relationship between Washington and LaFayette, often seen as the son Washington never had, in Lafayette's Tour.

And by way of advice, I recommend it to my Executors not to be precipitate in disposing of the landed property (herein directed to be sold) if from temporary causes the Sale thereof should be dull; experience having fully evinced, that the price of land (especially above the Falls of the Rivers, & on the Western Waters) have been progressively rising, and cannot be long checked in its increasing value.From the time of his youth, George Washington was convinced that America's future lay to the West. Over the decades he invested heavily in western lands in anticipation of that growth and his perpetual optimism is reflected in his instructions to his Executors.

In five separate provisions, the childless Washington, contrary to common practice, provided for the division of the 7,000 acre Mt Vernon property upon Martha's death. For large estates, the normal practice was to provide for transfer to one person to guarantee the continued economic viability of the property as well as the family's prestige and power. Instead, Washington divided the property among five nephews, with Bushrod getting the most valuable parcel, 2200 acres including the mansion house. Washington's true bequest was a united country, not maintaining the power of his descendants. There would be no continuing First Family.

And it is my express desire that my Corpse may be Interred in a private manner, without parade, or funeral Oration.Washington modeled his behavior on the leading citizens of the Roman Republic. Like Lucius Quinctus Cincinnatus, the legendary Roman who left his farm to take control of the state during an emergency, and promptly surrendered his powers when the emergency ended, returning to his farm, Washington astounded the European world, when with the treaty with Britain ending the Revolutionary War, he returned his commission to the Continental Congress and returned to his farm. His burial instructions followed the austere practice of classical Rome.

My Will and direction expressly is, that all disputes (if unhappily any should arise) shall be decided by three impartial and intelligent men, known for their probity and good understanding; two to be chosen by the disputants—each having the choice of one—and the third by those two. Which three men thus chosen, shall, unfettered by Law, or legal constructions, declare their sense of the Testators intention; and such decision is, to all intents and purposes to be as binding on the Parties as if it had been given in the Supreme Court of the United States.It is fitting that the will ends with a discussion of dispute resolution with an invocation of the name of the newly created supreme court of the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment