On September 18, 1675 Captain Thomas Lathrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was leading sixty soldiers and about twenty teamsters with wagons loaded with food in an evacuation of the Connecticut River valley village of Deerfield, Massachusetts. As they came to a small brook the lead soldiers stopped to rest to allow the wagons to catch up. For unexplained reasons, Captain Lathrop allowed his men to set aside their arms in order to gather grapes "which proved dear and deadly grapes to them" in the words of Increase Mather. While relaxing the group was attacked by several hundred Nipmuc Indians.

(19th century photo)

(19th century photo) Sixty of Lathrop's force (including Lathrop) were killed along with an unknown number of Nipmucs and the scene of the battle became known as Bloody Brook. It was one of the larger battles of

King Philip's War.

Wait a minute. "King Philip"?; War in Massachusetts?

King Philip's War started on June 20, 1675 when a band of Pokanokets Indians raided Swansea, Massachusetts. By the time the war ended in the fall of 1676 it had become, in terms of its consequences and the relative loss of life, the most significant conflict between Indians and European settlers in US history. And it didn't take place on the Great Plains or in the deserts of the Southwest (for another, more successful, Indian revolt occurring five years later see

Pueblo Revolt) - it was in New England.

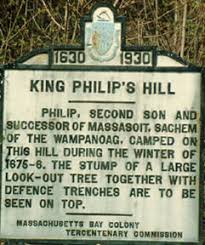

Although the war "started" with this attack, its origins went back fifty years to the original English settlements in Plymouth (1620) and Boston (1630) and the tangled history of provocations and misunderstandings between the settlers and the native Indian tribes. King Philip himself is an example of this complex history. He was the younger son of Massasoit, Sachem of the Wampanoag tribe, who had befriended and helped the Pilgrims at Plymouth during the colony's struggling early days. Philip's Indian name was Metacom but at the request of Massasoit's elder son, Wamsutta, the Plymouth authorities gave both sons English names which is how Metcacom became Philip and Wamsutta was renamed Alexander.

(No contemporary image of Philip exists)

(No contemporary image of Philip exists) For years, both sons moved back and forth between Indian and English societies. Alexander succeeded his father as Sachem until he died in mysterious circumstances while in English custody in 1662 (current modern speculation is that he had appendicitis and his death was hastened by medical malpractice by an English doctor) Philip became the new Sachem but his brother's death along with many other incidents led to his (and other Indians) increasing disaffection with their treatment by the English.

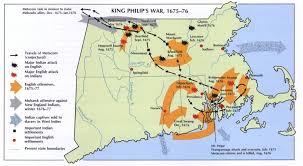

During the war, more than half of the 90 English settlements in New England were attacked and at the peak of Indian success, in the spring of 1676, it seemed possible that the only settlements left in English possession might be those on the Atlantic coast. The death rate for the English was twice that of the Civil War and 8X the rate in World War II. Thousands of the surviving settlers became destitute (New England's entire English population was only 52,000 at the time) and aid was hurriedly sent to the colonies from England and Ireland.

Rhode Island was devastated, with Providence and Warwick converted to pillaged ghost towns. Interior Massachusetts was largely abandoned with towns like Worcester, Deerfield and Marlboro destroyed and Sudbury (only 20 miles from Boston) and Chelmsford heavily damaged. All the settlements in Maine

were destroyed with the exceptions of York, Kittery and Wells. Connecticut suffered the least, with only Simsbury burned.

The outcome was even more disastrous for the Indians. An estimated 15% of the tribal population (including Philip) were killed. Many of the survivors were sold into slavery and transported to the West Indies and others sent to Bermuda where many of their descendants live today. Others migrated to New York and Canada. For the remnants, the pre-war relationships with the English would never be restored - though these were difficult before 1675, the situation became much worse in the aftermath of the war.

The impact of the war along with the continued French and Indian raiding threat from Canada slowed the settlement of interior New England for decades. Worcester, abandoned in 1675, was not resettled until 1722. Even six decades later, when Robert Rogers (founder of Rogers Rangers) was born in Methuen, Massachusetts it was still the northern limit of English settlement - only 50 miles northwest of Boston.

In contrast, it was only 42 years from the end of the Mexican War with its acquisition of the American southwest along with the settlement with England that brought us the Oregon territories to 1890 and the end of the Indian wars in the West.

The best account of the war is

King Philip's War: The History And Legacy Of America's Forgotten Conflict (1999) by Eric Shultz and Michael Tougias. Shultz and Tougias also do a good job tracing the different views of Philip throughout American history and from whom the quotes below are excerpted.

For most of the century after the War, Philip was regarded as a villainous figure with, for example, Reverend William Hubbard describing him as

"a savage Miscreant with Envy and Malice against the English"

Reading some of the references to Philip makes him sound like kind of a

Keyser Soze figure for New England children.

After the Revolutionary War and for much of the 19th century a different, and more sympathetic, Philip was portrayed. In Philip of Pokanket, Washington Irving wrote of him:

"Moved to hostility by the lust of conquest . . . He was a patriot attached to his native soil . . . a prince true to his subjects, and indignant of their wrongs . . . "

By the late 1800s, antiquarian Samuel Adams Drake was writing:

"In his own time he was the public enemy whom any should slay; in ours he is considered a martyr to the idea of liberty . . . "

By the mid-20th century historians were presenting a more tempered view of Philip as:

"more futile than heroic, more misguided than villainous"

And then in the latter part of the 20th century came the revisionist wave portraying Philip as:

"the innocent victim of Puritan skullduggeries".

In the end I think Shultz and Tougias get it right when they summarize these transformations:

"Like his portraits, descriptions of Philip's character often more adequately reflected the bias of the times than the life of a real flesh-and-blood man struggling to adapt to his rapidly changing world."

Frank Borman was the commander of the Apollo 8 mission which was the first to orbit the moon and transmitted back the dramatic photos of the Earth.

Frank Borman was the commander of the Apollo 8 mission which was the first to orbit the moon and transmitted back the dramatic photos of the Earth.