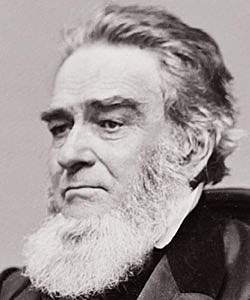

(Edward Bates, another Civil War guy with a beard)

(Edward Bates, another Civil War guy with a beard)

On this date in 1862, Attorney General Edward Bates, an appointee of President Abraham Lincoln, issued an opinion on the following question:

Is a man legally incapacitated to be a citizen of the United States by the sole fact that he is a colored, and not a white man?

The Attorney General's opinion was prompted by an inquiry from Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase. In turn, Chase's inquiry was triggered by an incident in which federal revenue cutter Tiger detained a schooner because it was commanded by a "colored man", in violation of a statute forbidding persons not citizens of the United States from such positions on American ships in the coasting trade.

The issue arose from a long history and specifically from Justice Taney's opinion in the Dred Scott case. Generations of legal historians have argued about whether Taney's opinion was an actual holding of the Court, or merely dicta, without legal authority, because it went far beyond the decisional grounds which had resolved the case. In any event, Taney's declaration that blacks, whether free or slave, could never be citizens of the United States, had practical and political impact. At a practical level it led President Buchanan's State Department to cease issuing passports to free blacks, and politically it enraged abolitionists and others opposed to slavery, raising the specter that the Supreme Court could eventually force northern states to recognize slavery (read A Second Dred Scott Case? for those implications).

Let's start at the end of Bates' opinion where he brusquely dispatches Taney's opinion.

In this argument I raise no question upon the legal validity of the judgment in Scott vs. Sandford. I only insist that the judgment in that case is limited in law, as it is, in fact, limited on the face of the record, to the plea in abatement; and, consequently, that whatever was said in the long course of the case, as reported, (240 pages,) respecting the legal merits of the case, and respecting any supposed legal disability resulting from the mere fact of color, though entitled to all the respect which is due to the learned and upright sources' from which the opinions come, was ^^ dehors the record,^' and of no authority as a judicial decision.With that, the Attorney General states with finality:

And now, upon the whole matter, I give it as my opinion that the free man of color mentioned in your letter, if born in the United States, is a citizen of the United States, and, if otherwise qualified, is competent, according to the acts of Congress, to be master of a vessel engaged in the coasting trade.

The path Bates follows to his conclusion is of interest as a matter of legal reasoning, the historical circumstances, and as reflecting commonly held views of blacks by whites, even by those who were against slavery.

Bates starts by noting an immediate problem - the lack of a "clear and satisfactory definition" of "citizen of the United States", and that most cases and opinions dealing with citizenship had "not turned upon the existence and the intrinsic qualities of citizenship itself, but upon the claim of some right or privilege as belonging to and inhering in the character of citizen."

In reading his opinion we must remember that in 1862 we are in a period before the adoption of the 14th Amendment and the establishment of a citizen of the United States as a uniform federal proposition. In 1862, citizenship was defined state by state.

Some claimed that the right to vote or hold office, as defined by each state, was an essential element of citizenship. Bates dismisses this notion, "No more in the case of a negro than in case of a white woman or child".

In the Attorney General's view:

In my opinion the Constitution uses the word citizen only to express the political quality of the individual in his relations to the nation; to declare that he is a member of the body politic, and bound to it by the reciprocal obligation of allegiance on the one side and protection on the other.

In a long passage, Bates acknowledges the practical realities where most blacks are, in fact, slaves, and its impact on thinking about citizenship.

It occurs to me that the discussion of this great subject of national citizenship has been much embarrassed and obscured by the fact that it is beset with artificial difficulties, extrinsic to its nature, and having little or no relation to its great political and national characteristics. And these difficulties, it seems to me, flow mainly from two sources. First, the existence among us of a large class of people whose physical qualities visibly distinguish them from the mass of our people, and mark a different race, and who, for the most part, are held in bondage. This visible difference and servile connection present difficulties hard to be conquered ; for they unavoidably lead to a more complicated system of government, both legislative and administrative, than would be required if all our people were of one race, and undistinguishable by outward signs. And this, without counting the effect upon the opinions, passions, and prejudices of men.

After writing that;

I have said that, prima facie every person in this country is born a citizen; and that he who denies it in individual cases assumes the burden of stating the exception to the general rule, and proving the fact which works the disfranchisement;

Bates goes on to discuss specifically whether slavery, color, or race constitute such exceptions.

As to slavery, "whether or not it is legally possible for a slave to be a citizen" is not within the scope of the question Bates is answering, which concerns a free person of color.

As to color, the Constitution contains "not one word on this subject", and goes on;

It has never been so understood nor put into practice in the nation from which we derive our language, laws, and institutions, and our very morals and modes of thought ; and, as far as I know, there is not a single nation in Christendom which does not regard the new-found idea with incredulity, if not disgust. What can there be in the mere color of a man (we are speaking now not of race but of color only) to disqualify him for bearing true and faithful allegiance to his native country, and for demanding the protection of that country?

From a modern perspective there are two aspects that stand out in this section. First is the distinction being made between race and color. Second is the concept that color as a disqualifier is a "new-found idea".

It's the discussion of race that Bates spends the most time on, and it is here that he makes clear the distinction that some make between color and race.

There are some who, abandoning the untenable objection of color, still contend that no person descended from negroes of the African race can be a citizen of the United States. Here the objection is not to color, but race only. The individual objected to may be of very long descent from African negroes, and may be as white as leprosy, or as the intermixture for many generations with the Caucasian race can make him; still, if he can be traced back to negroes of the African race, he cannot, they say, be a citizen of the United States!

This is the Attorney General's response:

Our nationality was created and our political government exists by written law, and inasmuch as that law does not exclude persons of that descent, and as its terms are manifestly broad enough to include them, it follows inevitably that such persons, born in the country, must be citizens, unless the fact of African descent be so incompatible with the fact of citizenship that the two cannot exist together. If they can coexist, in nature and reason, then they do coexist in persons of the indicated class, for there is no law to the contrary. I am not able to perceive any antagonism, legal or natural, between the two facts.

The opinion goes on to discuss state constitutions and some state court cases on citizenship and also addresses several other arguments against negro citizenship, one of which is that if negroes can be citizens, one might be elected President! Bates dismisses that argument:

. . . those who make that objection are not arguing upon the Constitution as it is, but upon what, in their own minds and feelings, they think it ought to be.

It is useful to understand the timing and historical circumstances surrounding the Bates opinion as well as his own background.

The opinion was issued on November 29, 1862. Lincoln had issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22 and would issue the final version on January 1, 1863. Though the Proclamation only impacted slaves in areas still held by the Confederacy it was part of a larger move, often prompted by Congress, to deal with slaves who had escaped into Union lines. Regardless of intentions when the war began in 1861, the inexorable logic of events was drawing Congress and the Administration down the road of not just ending slavery everywhere in the country under the 13th Amendment but of creating national citizenship, intended to include all regardless of color and the extension of voting rights to black males, done by the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Edward Bates was not an advocate of social equality for blacks. Born into a Virginia slave holding family, he moved to Missouri after the War of 1812. Bates became the first state attorney general after Missouri was admitted to the Union in 1820 and went on to serve many years in the state legislature. Politically he was a Whig, but joined the Republican Party after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska bill in 1854 (the same bill which caused Abraham Lincoln to become politically active again).

Though Bates opposed slavery, freeing his last slaves in 1851 and paying for their passage to Liberia, he was not an abolitionist. At the 1860 Republican convention he, along with Lincoln, Chase, and Seward, was a candidate for the presidential nomination. After his election, Lincoln asked all three of his competitors to join his cabinet. Although he supported Lincoln in his wartime actions and in the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, Bates remained hesitant about the role freed blacks should play in American society. He opposed Lincoln's initiative to allow blacks to join the Union army and I have been unable to determine whether he supported the extension of voting rights to male blacks. Finding himself increasingly at odds with the President, Bates resigned his cabinet post in December 1864 and died in 1869.